Uncovering the lives of first generation immigrants, letter by letter

Published on

Translation by:

CafébabelMore than ten million Germans crossed the Atlantic Ocean for the New World in the 19th and 20th centuries. According to various censuses, more than 43 million American citizens have German origins, and yet their ancestors' stories remain relatively unknown. Historians are working with citizens to fill this gap in historical records and to better understand the daily lives of these first generation immigrants. This is the first article in our new "Terrains Communs" series.

If you decide to go to New York for a few days, here's a tip: get up early, head to Battery Park on the South side of Manhattan and hop on a ferry that takes you to Ellis Island.

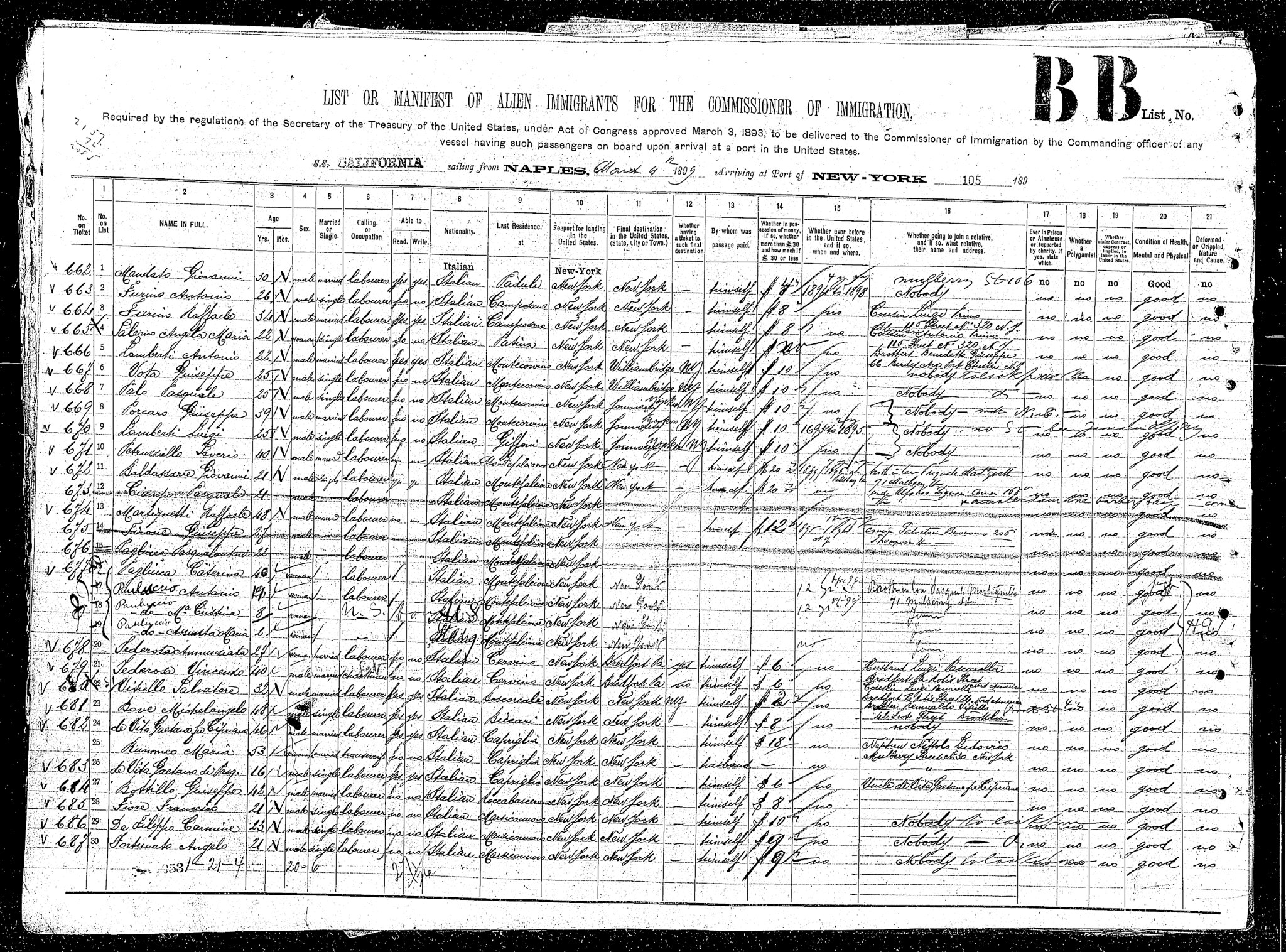

From 1892 to 1954, Ellis Island held one of the main immigration centres of the US federal government. It was there, on that very spot, that more than 14 million people first set foot on American soil.

That little island represented the beginning of the American dream. Ellis Island is now a museum, but a rather special one.

Every day, dozens of American families sift through the registers and other archives in search of their ancestors, who often arrived with just one small bag of possessions.

Precious correspondence

People of all ages, origins and nationalities made the momentous voyage across the Atlantic in search of one thing - The American Dream. Many, often forced by economic hardship to leave everything behind, maintained contact with their loved ones in Europe through letters.

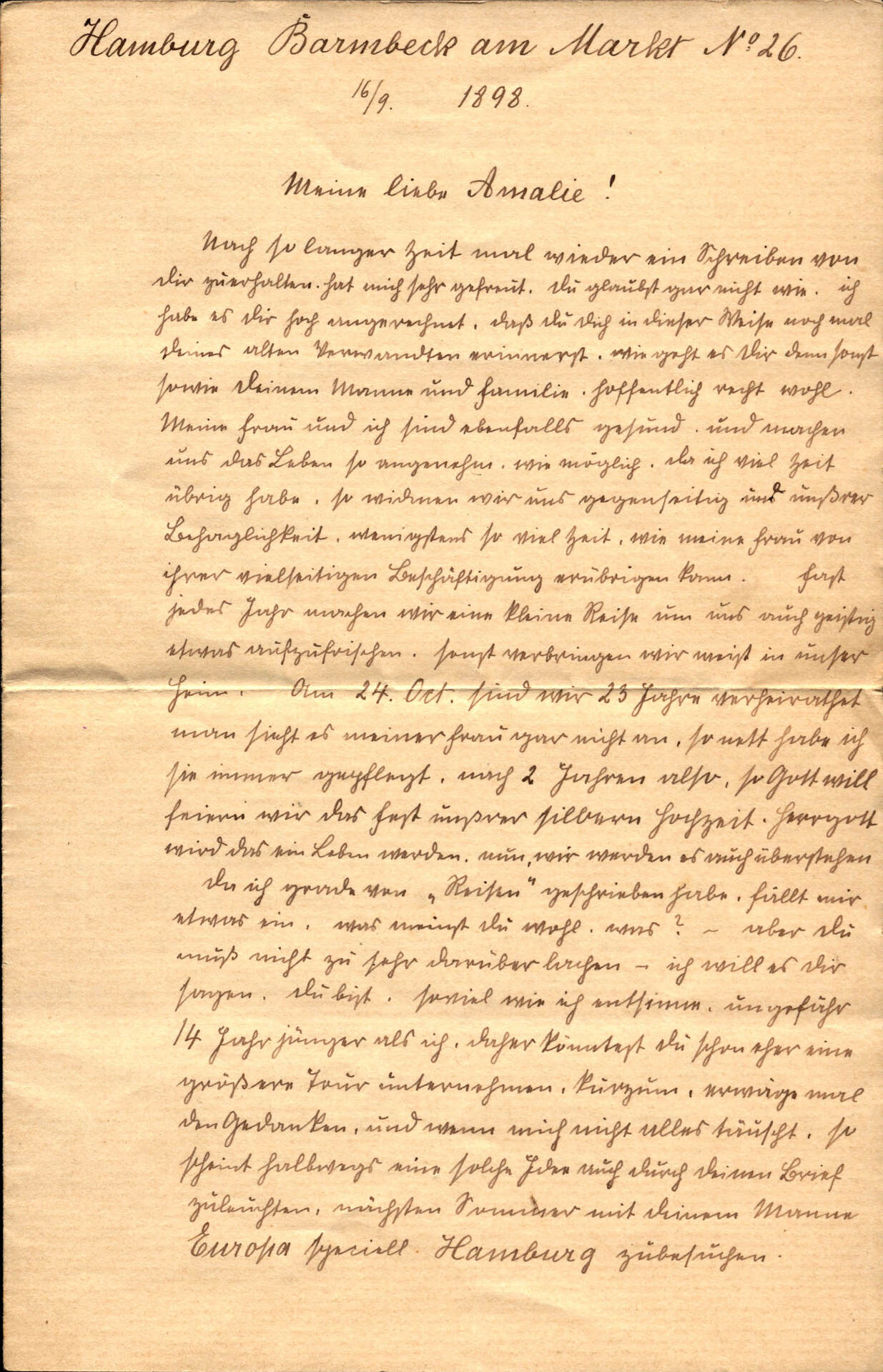

Literacy progressed throughout the 19th century, no longer limited to a small elite, allowing families to exchange correspondence for several years. In many cases these precious letters have been carefully preserved, passed down from children to grandchildren.

"Those letters are a goldmine of information" explains Jana Keck, a doctor at the German Historical Institute who is working on the COESO pilot project Growing migrant knowledge: Contemporary and historical perspectives.

The research project has recorded and digitised almost 3000 letters sent between German immigrants in the USA and their friends and families back in Europe, offering a different perspective on the history of exile and immigration.

These letters, which come from the personal archives of American families, have been transcribed, translated and published. They provide a context for daily life in both the United States and Germany.

“These letters are extremely valuable, [they allow us] to understand the lives of both Germans and those who emigrated" Jana Keck continues. We find out, for example, how the emigrants perceived their new daily lives, or economic information such as the price of livestock and eggs.

Instead of the popular, Gatsby-like success stories of European emigrants in America, we get the details of how normal people experienced exile from their homes, separation from their families and roots, and how they wanted to know about marriages, births or deaths.

Sunday Historians

What makes this particular citizen science project original, is its participatory approach.

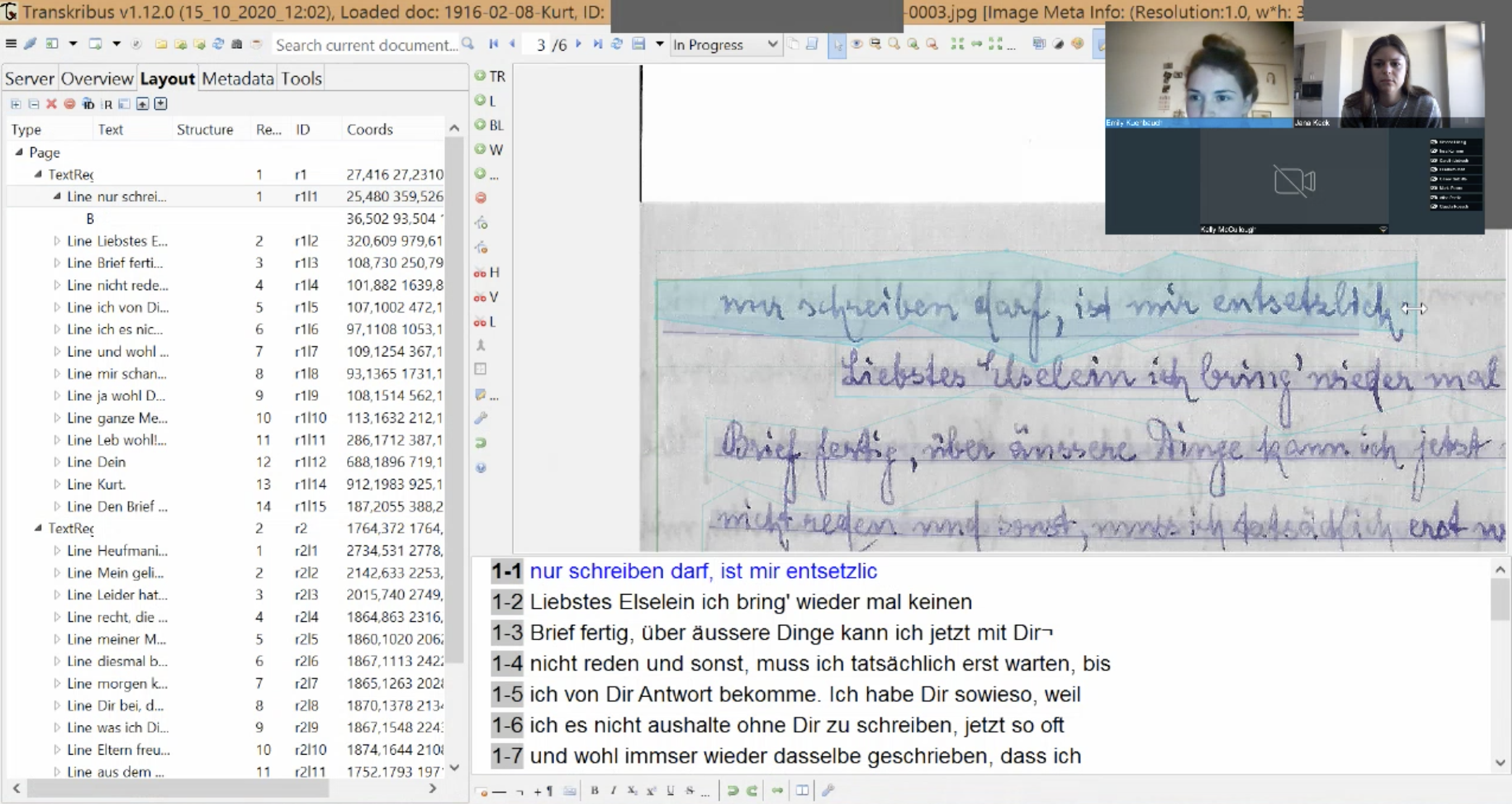

On both sides of the Atlantic, Americans and Germans were able to offer their personal archives, participate in the deciphering, and were trained to digitise or translate the letters. The transcription of the letters was also facilitated by the open source software Transkribus.

In Germany, the participants were mainly teachers or history students who saw it as a "hobby" according to Jana Keck. Some of the Americans, on the other hand, had more personal ties to the project.

“They are proud to have letters that are of historical importance!” says Keck.

“At first, they might not think that their grandmothers or grandfathers were heroes, or that they did anything particularly special with their lives. We don't agree! Those who had the guts to cross the Atlantic, to face uncertain futures, have their place in the History books!”

The citizens participating in the project can be referred to as what the French historian Philippe Ariès calls "L'Historien du dimanche" or “Sunday Historians”. Meaning people who are passionate about the past, and who contribute to historical research without being professionals.

Diving into the past

These epistolary archives also give us a comprehensive insight into rapidly changing societies. The letters contain references to the key political events of the 19th century.

We learn that German speakers who emigrated to the United States developed a 'German identity' even though Germany had not been officially created and the majority of Germans identified themselves primarily by their regional identities [editor's note: Germany was in fact a country in the same way as France or the United Kingdom in 1870, after the war between France and Prussia], that some were abolitionists in the midst of the American Civil War, or that others were already developing anti-Semitic undertones.

Many of the letters studied in this research project were correspondence between women. Some were also written by children, in order to teach them how to write. The texts are very conscientiously structured and composed, with a great amount of care; paper, ink, and stamps were still very expensive at the time. Writing to an aunt or uncle in the United States was an evening duty for children in German families.

“Writing was a family activity” explains Keck.

These letter exchanges also provide key accounts of the women who emigrated. At the end of the century [editor's note: 19th century], many women emigrated because they couldn’t find work in Germany and they worked in the city, for example as maids. Nevertheless, they had their own flats and were quite independent"_ ... unlike their sisters and cousins who stayed in Europe.

The letters tend to show that the women who stayed in Germany were less progressive on questions of women's rights but, according to Jana Keck, they "were fascinated" by the independence of the American women. “They didn't talk about it publicly, but listening to their sisters who had left the country, who were earning their own money and who were independent, must have made an impression on these women.”

The letters also show another reality. After leaving your country, emigrating, crossing the ocean and going into exile, there was no going back. The German community, unlike other immigrant communities, quickly incorporated American customs. Family names became Americanised, emotional ties were progressively weakened and the children of those who left no longer spoke German. Consequently, the letters gradually stopped.

Germany more open to the question of dual nationality

This project, which is one of the COESO pilot projects, will continue. Further research on letter exchange is planned in the USA, whilst in Germany the focus will be on training in digital tools in schools.

Transatlantic genealogical research projects still hold a lot of secrets which many Americans feel an almost visceral need to uncover, in the same way DNA tests, that can trace back your origins for a few dozen euros and a few drops of saliva, are popular.

If Americans possess original family documents, they can even apply for citizenship in their country of origin. Italy, Poland, Spain, Czech Republic, Norway, Slovakia have procedures in place for applicants who can prove the origins of their ancestors (birth certificates, baptismal or marriage certificates).

There are even specialised companies, such as Luxcitizenship, founded by Daniel Atz, an American-Luxembourger, which can be commissioned to process applications.

As for Americans who want to become German citizens, a new citizenship law is due to be debated this spring 2023 in the Bundestag, the German Parliament. The text could facilitate dual citizenship and acknowledge the reality that Germany is no longer a country of emigration, but of immigration. For the time being, only Jewish emigrants whose nationality was revoked by the Nazi regime before World War II can have a German passport in addition to their American nationality.

This story is part of the Cafébabel series "Common Grounds"

This project is in collaboration with the research project COESO (Collaborative Engagement on Societal Issues), at the intersection of social sciences and participatory research. Coordinated by l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, COESO is funded by the Horizon 2020 research programme. The content of this article can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission, and the Commission is not responsible for the information contained herein.

Banner: An advertising poster of the Cunard Line © U.S. Congress Library

Translated from D’une lettre à l’autre, des égo-histoires d’exils