Europe fears a new Yellow Peril

Published on

Translation by:

eleanor forshaw

eleanor forshaw

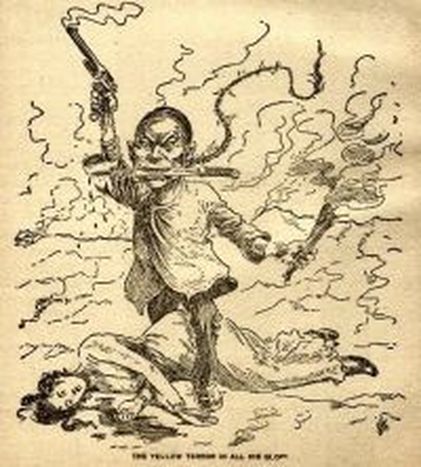

Napoleon once said, “when China awakens, the Earth will tremble”. Surprising words from someone who feared so few. So it seems that fear of China in the western world is nothing new.

Paris, May 1968. The general insurrection of numerous and organised Maoists made Gaullist France tremble. That year, all the revolutionary thinking that stemmed from Marxism and Leninism discovered the precepts of Maoism and renewed its struggle against capitalism. It was a time during which 'the Yellow Peril' was tinged red. China, following in the steps of the USSR but with a more popular form of communism than that struggling under the weight of Stalinism, threatened the basis of western nations by bringing class struggle, once more, to the forefront. It came at a time when the youth of France was ready to take to the streets.

Demonisation of Chinese capitalism

Other times, other customs. A wave of fear swept the European Union last January following the lifting of the “Multi-Fibre Agreement”. The decision was ratified during negotiations within the World Trade Organisation, thus signalling the end of quotas imposed by Europe on imports of Chinese textiles. Peter Mandelson, European Commissioner for Trade, said in April 2005, “there is reason to be worried. Europe cannot stay put and do nothing”.

Europe’s fear of China has met with some ironic quirks: as the sworn enemy of western capitalism a mere 30 years ago, it is as an emerging power of this very same capitalism that China now instils fear in Europe. Governed today by the iron fist of a so-called communist administration and converted to the principles of market economy, China embodies the terrifying image of a highly capitalist world bent on profit-making, ignoring the most elementary of democratic principles, ranging from the respect of human rights to working conditions.

Media torn between criticism and celebration

China is often criticised for embracing globalisation and its failings. But one must remark that China also receives praise for its sustained economic growth, estimated at around 9% per year ever since 1978. Manel Olle, professor in the department of Asian and Oriental Studies at the university of Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, reminds us that the image of China in the media tends to oscillate between eulogy and blame, depending on whether we concentrate on the speed of its economic development or on the social inequalities that it generates and its persistent lack in political liberties.

According to Manel Olle, these variations seem to follow rather accurately the state of the relationship between the United States and China. Thus, with then President Jiang Zemin’s journey to the USA in 1997 and the returned visit of his American counterpart Bill Clinton in 1998, the American press – and, by extension, the European press – seemed to suddenly discover that China was not as menacing or badly intentioned as previously thought. The dramatic events at Tiananmen Square in June 1989, when the army repressed student uprisings by killing almost 1,400 people and wounding a further 10,000, was a different story.

Who is to blame?

When trying to avoid falling into the trap of media U-turns, there are two things to remember. Firstly, when we talk about the ‘Yellow Peril’ and demonise China for having become the sweatshop of a deregulated world, creating products at a derisory price and placing them on the international market, we must not forget that many of those responsible for maintaining Chinese manual labour in unacceptable conditions are actually Western companies. For instance, the factory making Timberland shoes, known as Kingmaker in China, employs 4,700 people – 80% of them are women and there is an indeterminate but significant number of children working for 45 pence an hour, 16 hours a day. Similarly, Puma makes its employees work 16 hours a day in the Cantonese town of Dongguan, with only one day off every two weeks. Secondly, China is so big, complex and contradictory, that we can, from one moment to the next, present radically opposed stereotyped images. They may not be false, but they are limited to small realities which are not representative of the entire country.

Translated from L’Europe et l'angoisse du « péril jaune »