Mali elections - testing a young democracy

Published on

Translation by:

joanna allan

joanna allan

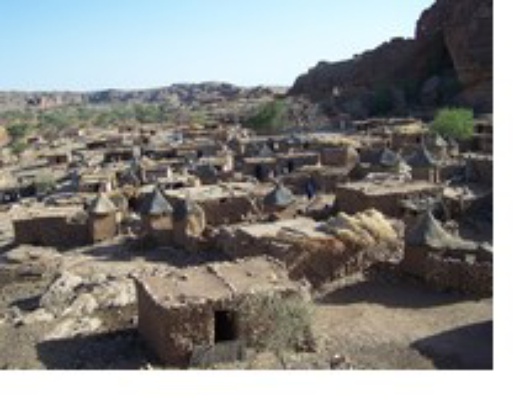

A 13 million strong largely Muslim population, a surface area three times the size of Germany. Alongside Senegal, Mali is a democratic model for western Africa

On 27 April, Mali held the first round of its presidential elections. Irene Horejs, head of the Delegation of the European Commission, spoke to us before the results came out.

Taking European elections as a reference, what are the strong and weak aspects in Mali's case?

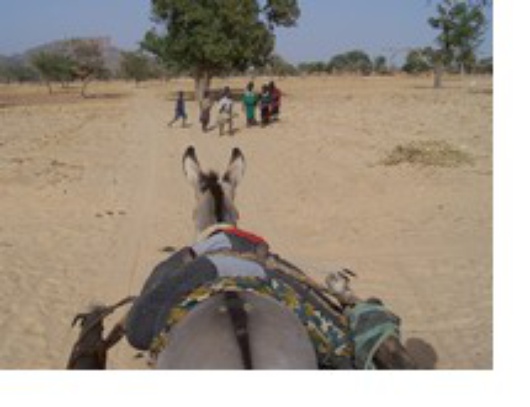

Mali is a huge country with profound infrastructure shortages. It's difficult to organise any event, such as elections, on a national scale. Furthermore, its wide linguistic diversity (with 15 widely spoken languages), and the nomadic nature of a sector of the population, makes everything a little more complicated. These include difficulties in registering voters and handing in cards on time, staff training, distribution of hundreds of ballot boxes, etc.

One should bear in mind the enormous limitations of the electoral budget in a country like Mali. Another factor which we are unfamiliar with in Europe but which is very much present here, is the sense of belonging to a certain ethnic group. This is a crucial factor at the moment of issuing the vote.

From a more technical point of view, the fact that Mali was a French colony until 1960 has not only influenced the structure of the parties on a national level, but has also determined that the electoral model is very similar to the French. On a local level and in terms of contact with the people, the organisation of the elections retains very Malinese characteristics.

From a more technical point of view, the fact that Mali was a French colony until 1960 has not only influenced the structure of the parties on a national level, but has also determined that the electoral model is very similar to the French. On a local level and in terms of contact with the people, the organisation of the elections retains very Malinese characteristics.

What type of help has the European Union provided for the electoral process?

Our role has been limited to financing local electoral education projects. It's about the population making use of its right to elect and doing it in freedom, as well as incorporating behavioural guidelines for the day of the vote. We can say that after fifteen years of healthy democracy, Mali has its own instruments for ensuring electoral transparency.

Mali is one of the poorest countries on the Earth (175 out of 177 on the UN development index). Does the population view these elections with the hope that the result might in some way alleviate their harsh daily conditions?

Participation in the last presidential elections in 2002 was less than 40% (Mali traditionally has one of the lowest voting rates in the world). Therefore, one of the main goals is to increase participation. Bamako (the capital), and along with it the government, are perceived as very distant by a large sector of the population. Furthermore, the high grade of decentralisation encourages a relative disconnection between the population and state administration.

Participation in the last presidential elections in 2002 was less than 40% (Mali traditionally has one of the lowest voting rates in the world). Therefore, one of the main goals is to increase participation. Bamako (the capital), and along with it the government, are perceived as very distant by a large sector of the population. Furthermore, the high grade of decentralisation encourages a relative disconnection between the population and state administration.

What are the possibilities of Amadou Toumani Touré, president since 2002, leaving the position?

To be honest, very slim. That doesn't mean that the maturity of democratic changes in Mali should be put in doubt. It corresponds to the enormous popular support of the president, who, incidentally, isn't attached to any party. In fact, the Malinese political scene is formed by more than one hundred parties, although only four of them really count in these elections, the result of which will predictably be another coalition government.

This plurality can also be noticed in the media. Although it's true that during its electoral campaign, the government to some extent has taken advantage of its control over the state television channel, it's the radio where every candidate has his/her opportunity. Given the lower cost of a radio set and the better reception and higher number of transmissions, every candidate reaches the homes of Mali via this medium.

Translated from Irene Horejs: Mali cuenta con sus propios instrumentos de transparencia electoral