Jewish life in Budapest: A tale of two cities

Published on

Three years after jobbik became the third largest political force in parliament, the ultra-nationalist party has been accused of once again whipping up anti-semitic feeling. As observers fear a creeping upsurge in nationalist and xenophobic discourse, what chance of revival is there for the jewish community in a city that so many of their ancestors once called home?

Veering off one of Budapest’s vast Parisian-style boulevards, I plunge into the gloom of Dob Utca, one of the streets in the so-called ‘jewish quarter’ that comprised the wartime ghetto in District VII. A curious mix of kosher restaurants, second hand clothes stores and the labyrinthine Romkocsma populate the area and the architecture is a blend of ornate, fading façades and dull grey walls some peppered with bullet holes.

Despite Budapest being home to one of the world’s second largest synagogues, Eduard Deblinger tells me that the country’s orthodox community has dwindled to ‘only a few hundred’. Is the president of the Hungarian autonomous orthodox israelite congregation a shepherd without a flock? 'People travel to Israel to live a more religious life, and because it’s difficult here, they don’t return,' says Deblinger. 'We receive a lot of orthodox tourism but people are putting Hungary at the bottom of their lists because of the anti-semitism they hear of.'

Despite Budapest being home to one of the world’s second largest synagogues, Eduard Deblinger tells me that the country’s orthodox community has dwindled to ‘only a few hundred’. Is the president of the Hungarian autonomous orthodox israelite congregation a shepherd without a flock? 'People travel to Israel to live a more religious life, and because it’s difficult here, they don’t return,' says Deblinger. 'We receive a lot of orthodox tourism but people are putting Hungary at the bottom of their lists because of the anti-semitism they hear of.'

Scandals

As Hungary was still reeling from a jobbik MP’s ‘lists of jews’ furore in November 2012, the student council at the social sciences faculty in Hungary’s oldest university ELTE was suddenly suspended, accused of allegedly keeping illegal databases containing derogatory comments on first year students. The insults supposedly ranged from descriptions of girls’ or hipsters’ appearance to the ominous listing of political persuasion, sexual orientation and whether jewish or not. 'There was a lot of wilful ignorance or denial from university teachers that basically the department to a very large extent became a stronghold for the jobbik party,’ says Kristof Domina, director of the Budapest-based Athena Institute. ‘The student council decides who receives subsidies for their education; the question is if these people were discriminated against.’

Read 'Magyar muslims: Budapest’s integrated communities' on cafebabel.com

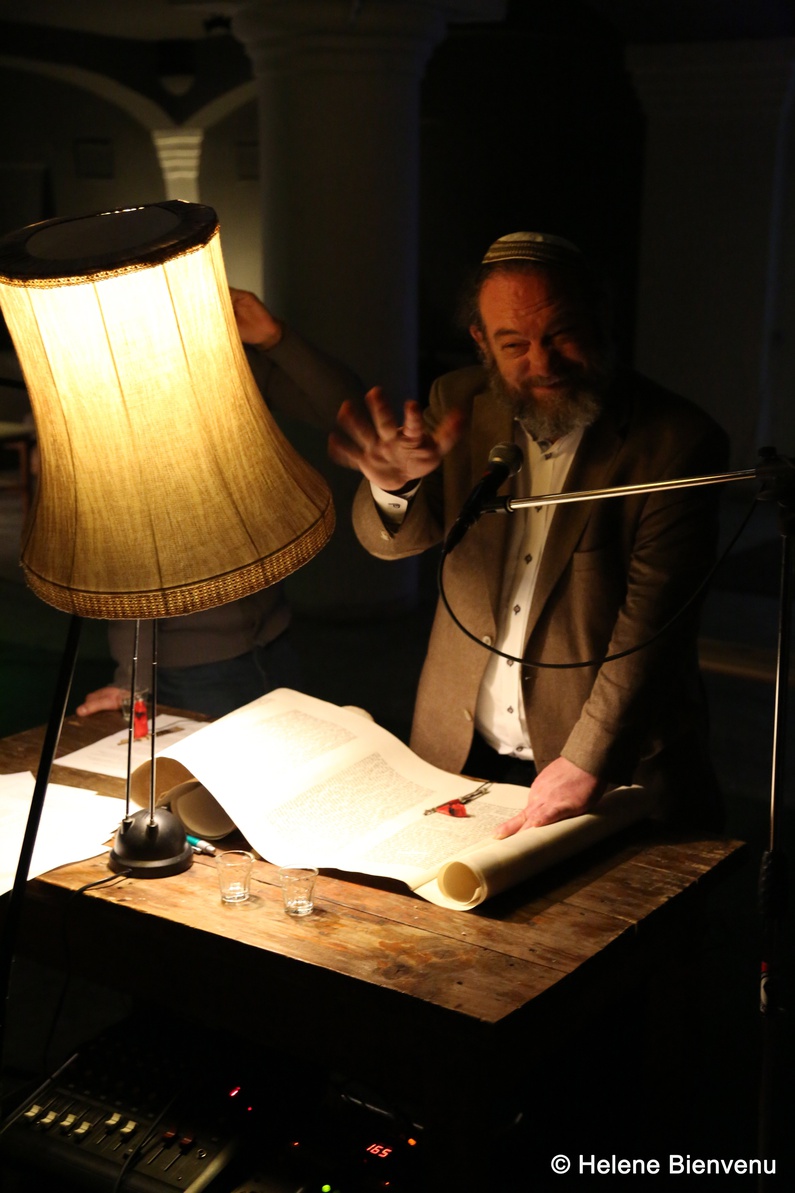

This latest scandal breaks in the build-up to Purim, a festival celebrating the salvation of the jews in ancient Persia. The jewish cultural youth group Marom have organised a grand party at Siraly café; in an act of defiance and ridicule, a dress code has been hastily added – minorities that feature on the student council’s now notorious lists. For the main ceremony and the traditional recital of the book of Esther or 'Megillah', I am given only one instruction – ‘drink’. In the smoky confines of the basement David Lazar, the visiting chief rabbi of Stockholm, pauses to gulp down a shot of vodka before continuing to chant. Throughout the 45-minute recital, spoken simultaneously in Hebrew and Hungarian, the assembled crowd of young Budapestians nod along, chat to friends, order beer and break out into a regular chorus of ‘Haman!’ followed by much stamping of feet and trills of noise-makers every time the tale’s villain is mentioned.

Purim, often referred to as the carnival of the jewish calendar, is a traditionally rowdy affair. Marom’s party stands in sharp contrast to the comparatively chilly and demure atmosphere of the city’s synagogues. This, says the rabbi, is precisely the point. 'It's very important in the 21st century to recognise that not all jewish expression is done through the synagogue. This fantastic group found a way to combine both their jewish roots, practices and prayer together with social action on behalf of their country, which is going through rough times.'

Purim, often referred to as the carnival of the jewish calendar, is a traditionally rowdy affair. Marom’s party stands in sharp contrast to the comparatively chilly and demure atmosphere of the city’s synagogues. This, says the rabbi, is precisely the point. 'It's very important in the 21st century to recognise that not all jewish expression is done through the synagogue. This fantastic group found a way to combine both their jewish roots, practices and prayer together with social action on behalf of their country, which is going through rough times.'

Shtiebels and shoes

Under nazism, jews were deported and killed. Under communism, jewish community organisations were suppressed. Is this the generation that can rebuild Budapest's jewish soul? 'Many of us grew up with no real connections with our identity,’ says Lacko Bernath, a history student and Marom member. ‘It's a tragedy that you feel that you're connected to your jewishness only when you see a nazi on the TV or a far right politician who is an idiot. You cannot find your identity from negative communication. That's what we are working to change.’ Other attendees are more cautious. ‘There is worse than jobbik, but I would definitely flee to Israel if they ever got into power. I know a lot of jews that would,’ says Bence Kovacs. As tables and scrolls are packed away, the DJs fire up the music and the audience streams out onto the dance floor to continue the festivities. In some interpretations of the Talmud, Purim requires one to get so intoxicated that you can no longer tell the difference between good and evil. The gyrating crowd at Siraly probes this ethical matter until an indeterminate hour of the morning.

Under nazism, jews were deported and killed. Under communism, jewish community organisations were suppressed. Is this the generation that can rebuild Budapest's jewish soul? 'Many of us grew up with no real connections with our identity,’ says Lacko Bernath, a history student and Marom member. ‘It's a tragedy that you feel that you're connected to your jewishness only when you see a nazi on the TV or a far right politician who is an idiot. You cannot find your identity from negative communication. That's what we are working to change.’ Other attendees are more cautious. ‘There is worse than jobbik, but I would definitely flee to Israel if they ever got into power. I know a lot of jews that would,’ says Bence Kovacs. As tables and scrolls are packed away, the DJs fire up the music and the audience streams out onto the dance floor to continue the festivities. In some interpretations of the Talmud, Purim requires one to get so intoxicated that you can no longer tell the difference between good and evil. The gyrating crowd at Siraly probes this ethical matter until an indeterminate hour of the morning.

In the run-down yet vibrant District VIII, a non-descript courtyard in Teleki Square conceals the entrance of a unique synagogue in Budapest. Formed by hasidic jews from Ukraine in the late 20th century, this little prayer house or ‘shtiebel’ is the last of its kind. It has been rescued from abandonment by the community. It’s another Purim festival here and the shitebel’s pious founders would be proud of the faithful restoration, if slightly shocked by the dressing up – a pirate welcomes me in whilst an alien offers me a shot of Palinka. This is a far cry from the ‘jewish quarter’, as the shtiebel’s chairman Andras Mayer explains. 'Our ancestors would be insulted by that name. They took part in the 1848 revolution, fighting the Austrians together. They considered themselves as Hungarians with a jewish religion.’ And what of the jobbik party, whose headquarters are not far from here? 'This is not just a jewish issue. Any sane human being who has anything to do with democracy should be against them.'

'Our ancestors considered themselves as Hungarians with a jewish religion’

A light rain passes over the Danube and water collects inside a child’s shoe on the river’s edge. The ‘shoes on the Danube’ memorial instils a profoundly uneasy sensation. One stands on the same spot where, during world war II, jewish men, women and children were lined up, ordered to remove their shoes and then executed by gunmen of the fascist arrow cross party, falling into the lapping water below and carried away by the current. It is a common sight to see attendees of jobbik’s political rallies hoist flags and wear insignia eerily similar to that of arrow cross. Although there seems to be encouraging signs of jewish community engagement through subversive and colourful events, some minds in Budapest fear that, unless the country urgently confronts and dissects its complex recent history, the voices of sanity risk being swept away.

Special thanks to Ráhel Németh of cafebabel.com Budapest, and Nora Feldmar

Special thanks to Ráhel Németh of cafebabel.com Budapest, and Nora Feldmar

This is the first in a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Athens, Warsaw, Naples, Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind

This is the first in a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Athens, Warsaw, Naples, Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind

Images: main © Hélène Bienvenu; in-text 'rabbi hand' and ‘cowboy purim’ © Hélène Bienvenu; ‘kosher sign’ and ‘danube shoes’ © Andrew Connelly; homepage image crops of girl by shoes monument by (cc) archer10 (Dennis)/ Dennis Jarvis/ flickr