In the eye of the storm

Published on

Translation by:

Ed SaundersHow young activists in Russia are overcoming the illusion of power

‘On 5 May there was a demo for the legalisation of hemp in downtown Moscow. They arrested three participants. As usual a group of us went down afterwards and asked the reason why. The officials said, come up to the guard house, we’ll explain everything there. They detained us, twisted our arms behind our backs, threw us onto the tarmac and slammed the guys’ faces into the ground. They throttled us and arrested ten people. Then they accused us of promoting drugs and resisting state authorities’.

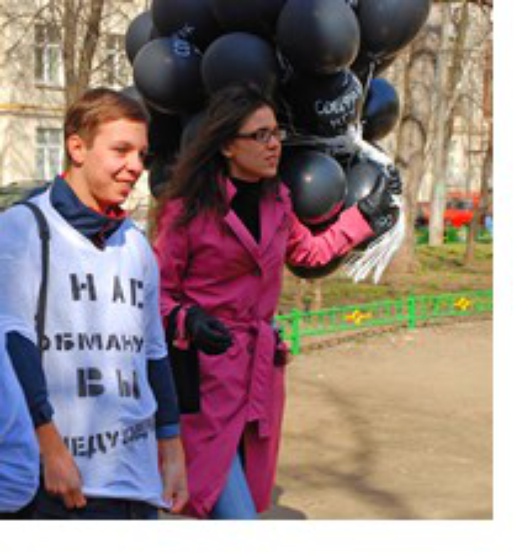

Julia, 25, laughs in disbelief as she recalls the events she describes. ‘We only demanded the legalisation of hemp. That’s legal! It took the court all night to deal with our cases. The girls were fined; the guys got ten to fifteen days detention’. For the past six months, Julia’s group of YHRM activists have been concentrating on putting the constitutional right for freedom of assembly into practice. It is a never ending task – due to numerous violations of the law by the state.

Daddy Kremlin

The Russian state, as the European media have been saying for a long time, is a power machine that increasingly suppresses the freedoms of its population. The Kremlin is at the centre, and the president is in the driving seat. It’s an opinion backed up by the stories of people like Julia. However, she has more in common with official propaganda than it seems. Like the Kremlin’s propaganda, Julia is fixated with the state and sovereignty. ‘The Russian people always need a father’, says a young man, who describes himself as a ‘free radical’. Can it be that this fixation with authority is what makes people powerless in the face of power? ‘The Kremlin creates the reality on the edges of which the ‘democrats’ fight for ‘freedom’. The weak opposition are spinning in the draught of a storm, in the eye of which Putin, the Kremlin, and Moscow are imagined. Everything spins around this eye, which alone watches and rests. Russian roulette threatens all those who rebel against this central core.

The Russian state, as the European media have been saying for a long time, is a power machine that increasingly suppresses the freedoms of its population. The Kremlin is at the centre, and the president is in the driving seat. It’s an opinion backed up by the stories of people like Julia. However, she has more in common with official propaganda than it seems. Like the Kremlin’s propaganda, Julia is fixated with the state and sovereignty. ‘The Russian people always need a father’, says a young man, who describes himself as a ‘free radical’. Can it be that this fixation with authority is what makes people powerless in the face of power? ‘The Kremlin creates the reality on the edges of which the ‘democrats’ fight for ‘freedom’. The weak opposition are spinning in the draught of a storm, in the eye of which Putin, the Kremlin, and Moscow are imagined. Everything spins around this eye, which alone watches and rests. Russian roulette threatens all those who rebel against this central core.

Mastering the hurricane

Dmitrii Makarov’s revolution aspires to something greater than this kind of merry-go-round, da capo al fine. ‘Our work is about creating a new social space where human rights will be observed’, the YHRM lawyer says. There are spaces where this plan is more effective than on Moscow’s streets – like the sociological faculty (SozFak) of Moscow State University (MGU). Along with a group of dissatisfied students, Dmitri and the YHRM have succeeded in opposing the state’s rhetorical storm with something of their own.

From Dmitrii’s point of view the conditions at the SozFak are like an authoritarian political system in miniature: ‘There was a strict regime under a dean, and a passive student majority. Dissatisfied dissidents debated the situation in the kitchen of the student halls’. A handful of critical students founded the action platform 'od group’. ‘The dean appoints the members of the Scientific Committee and the Committee in turn elects the dean,' says Alexandrina, as she explains the SozFak hierarchy. 'It is a closed circle’. ‘At one meeting student reps stood up and criticized us strongly,' adds fellow protester Elia. 'They even called us extremists’. According to Elia, critical voices have been placed as ‘provocateurs’ to ‘threaten the state order’. The teaching at the faculty is also poor – current theories are not taught, and almost no discussion takes place in seminars. Many students obtained places at the faculty by paying bribes, and not through knowledge or interest.

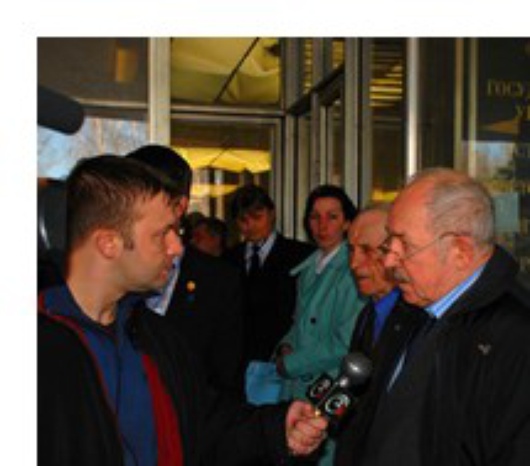

At the beginning of the year the ‘od group’ began staging protests. On 28 February they distributed flyers with their demands in front of the faculty. After only a few minutes, the students were arrested for ‘unauthorised use of mass media’. The incident became a political issue because the independent radio station Echo Moscow and various newspapers were at the scene. Vladimir Dobrenkov, the dean of SozFak, denounced the students’ actions as ‘extremism’. The students defended themselves. They succeeded in obtaining the appointment of a commission to investigate the teaching quality by petitioning the director of MGU, the Ministry of Education and the State Social Forum. As a result, they held up management with promises of a slow change; the Social Chamber judged the lessons to be of poor standard, and Education Ministry experts discovered that the dean of the SozFak had copied material for the majority of his textbooks – plagiarism!

At the beginning of the year the ‘od group’ began staging protests. On 28 February they distributed flyers with their demands in front of the faculty. After only a few minutes, the students were arrested for ‘unauthorised use of mass media’. The incident became a political issue because the independent radio station Echo Moscow and various newspapers were at the scene. Vladimir Dobrenkov, the dean of SozFak, denounced the students’ actions as ‘extremism’. The students defended themselves. They succeeded in obtaining the appointment of a commission to investigate the teaching quality by petitioning the director of MGU, the Ministry of Education and the State Social Forum. As a result, they held up management with promises of a slow change; the Social Chamber judged the lessons to be of poor standard, and Education Ministry experts discovered that the dean of the SozFak had copied material for the majority of his textbooks – plagiarism!

Climate change

In the meantime the ‘od group’ protest had set something in motion: a growing critical public had formed. Scientists, journalists and citizens from home and abroad had declared solidarity with the ‘od-group’. Above all, however, a change of climate had set in at the faculty. Students thinking critically are appearing with previously unknown self-confidence. These successes represent only a partial victory, however, as long as further measures from the MGU management fail to materialise.

In the meantime the ‘od group’ protest had set something in motion: a growing critical public had formed. Scientists, journalists and citizens from home and abroad had declared solidarity with the ‘od-group’. Above all, however, a change of climate had set in at the faculty. Students thinking critically are appearing with previously unknown self-confidence. These successes represent only a partial victory, however, as long as further measures from the MGU management fail to materialise.

The actions of the ‘od group’ are already having an effect far beyond MGU. Stories about the small revolution are being spread via the internet and personal contacts across the whole country. The dean has become a figure of fun. The success story is a symbolic resource that could help young people to laugh about those in power and to become active themselves. All this in a country where everyone looks to the Kremlin, and as a result the Kremlin alone sees everyone.

In-text photos: eye of the storm (Riz Ainuddin/ Flickr), activists/ journalist (Evgeniya Demina)

Translated from Im Auge des Orkans