Europe and the Great White North

Published on

As a G8 member, a middle power and a welfare state, Canada has much to gain from collaboration with the EU. But while Canadians have no great animosity towards Europe, they have no great interest in it either.

The Canadian world view is, above all, Anglocentric. This might come as a surprise from a country that prides itself on being both bilingual and multicultural. On a political level, Canadian governments may be savvy enough to cooperate with European partners, particularly in the area of foreign policy. However, domestic culture and politics in Canada remain primarily influenced by the two English speaking world powers, the United States and the United Kingdom. Europe, as a western industrialised region, ranks third as an influence on Canada, but the European Union itself does not feature in the Canadian political consciousness at all.

Between the old world and the new

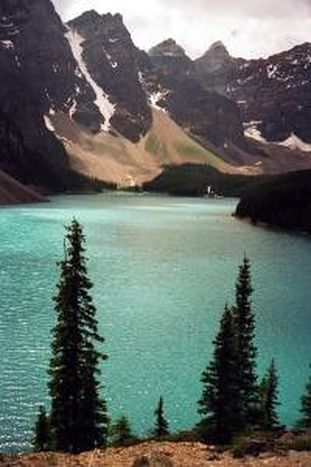

Canada’s biggest neighbour, trading partner and cultural influence is unequivocally the United States. Like most of the world, Canada can hardly escape the onslaught of the American media industry and, although differences in governance and social attitudes are pronounced, much of the material culture is the same. Europe, meanwhile, is associated with “high culture” which Canadians mistrust in favour of hard work and out-door pursuits.

Canada’s relationship with the former colonial powers has greatly diminished over the last century and the influence of the United Kingdom owes more to the hegemony of English-speaking culture in the world than to its colonial past. Indeed, English Canadians look at the British with a mixture of curiosity and bemusement; Brits are perceived as very formal, old fashioned and a bit eccentric. While the role of the Queen of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as Canada’s head of state is a minor thorn in the side of French Canadians, it is a formality most English Canadians rarely think about, particularly the younger generation.

The relationship between French Canadians and France is slightly more fraught, with the former still harbouring resentment towards the latter for trading them off to the English for a piece of India in the 18th century. The Quebecois and other French Canadians also tend to pride themselves on their hard-working, salt-of-the-earth origins and their local culture, and consider themselves less pretentious than their French forbears. Meanwhile the French, despite their rhetoric concerning the Francophonie, take a particularly patronising view of other French-speaking countries and former colonies - usually protesting that they cannot understand them.

Language and culture

The dominance of English-speaking culture in Canada may also be a consequence of the “cultural mosaic” it enjoys. In addition to the original colonial powers, France and Britain, Canada has significant European populations from southern Italy, Greece and Portugal, as well as Poland and Ukraine. Since English is the world-wide lingua franca, it is a point of reference for these disparate groups living together in Canada.

The extent to which language has moulded the Canadian collective consciousness has been thrown into relief by the recent spate of terrorist attacks around the world. While attacks occur globally on a regular basis, the bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York provoked at least a week of outrage and mourning in Canada. The recent London bombings were similarly major news items that were marked by minutes of silence across Canada. The Madrid bombings, by contrast, went almost unnoticed.

Culture versus politics

But while Canada may be culturally Anglophone, its administration is largely Francophone (as are the majority of Canadian Prime Ministers). This is because Francophones are more likely to be bilingual, a requisite in the civil service, and retain the French deference for the civil service which is often distained in English Canada. However, the political similarities and common interests Canada shares with France and other European countries, and indeed with many pillars of EU policy, go completely unnoticed in the domestic arena. Public spending and regulation, for example, is higher in Canada than in the United States, but lower than in Europe. Canadians feel superior to the US for this reason, but never inferior to Europe, nor do they think to make this comparison.

The touchstones of Canadian identity are the principles of tolerance, the social safety net and multilateralism. Like the EU, Canada makes significant “equalisation payments” from richer to poorer regions. Canadians never speak of a “social model,” and are vaguely suspicious of any thing “socialist,” although they are universally proud of the free healthcare system. Canadians are also proud of their role in peacekeeping, international accords like Kyoto and the Anti-Landmine Treaty, and the United Nations but still remain stuck in the shadow of the American elephant next door. As for the EU, the average Canadian would be hard put to say what it is.