Budapest: Your Education, My Emigration

Published on

Translation by:

Kait BolongaroTwo years ago, reforms in higher education in Hungary caused widespread outrage and led many young citizens to pursue happiness abroad. Today, the battle rages on. Is it reasonable to grant students a scholarship in exchange for working in Hungary for as long as they have studied? A photo essay from Budapest.

In response to the wave of emigration of educated students from the country, many of which are heading to Austria or Germany, the Hungarian government announced a reform of the system of higher education. Results? Students receiving scholarships (the only way to study for free at state universities) have to sign a declaration promising to work in Hungary upon graduation for as many years as the have studied. In addition, 16 disciplines are no longer eligible for scholarships, including law, economics and sociology. Why? The need to invest in so-called disciplines of the future: sciences and technology. Financing for universities has decreased by 40% since the reform passed two years. What is the situation now?

Beginning of Reforms

The announcement of changes provoked a lively response from secondary school students and teachers. There were numerous protests organised mostly by the student-teacher organisation Hallgatói Hálózat (HaHa). The group presented six demands: the overall reform of public and higher education; the return to the previous number of scholarships (cut by 3/4s); stop further budget cuts; the abolition of student contracts; not limit the autonomy of universities and open up studies to poorer students. The government did not accept the invitation to mediate. The organisation has been accused of collaborating with opponents of Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People's Party — the ruling coalition.

The announcement of changes provoked a lively response from secondary school students and teachers. There were numerous protests organised mostly by the student-teacher organisation Hallgatói Hálózat (HaHa). The group presented six demands: the overall reform of public and higher education; the return to the previous number of scholarships (cut by 3/4s); stop further budget cuts; the abolition of student contracts; not limit the autonomy of universities and open up studies to poorer students. The government did not accept the invitation to mediate. The organisation has been accused of collaborating with opponents of Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People's Party — the ruling coalition.

Egyetem Square, where students and teachers from Apáczai Csere János Secondary School organised a silent protest two years ago. After a speech outlining the changes introduced by the reforms, the students stood in silence on the benches for several minutes.

Egyetem Square, where students and teachers from Apáczai Csere János Secondary School organised a silent protest two years ago. After a speech outlining the changes introduced by the reforms, the students stood in silence on the benches for several minutes.

The reform also introduced changes to secondary schools. The new legislation made schooling mandatory until the age of 16, instead of 18. As a result of funding cuts, some schools in smaller towns have begun to close.

The reform also introduced changes to secondary schools. The new legislation made schooling mandatory until the age of 16, instead of 18. As a result of funding cuts, some schools in smaller towns have begun to close.

High School's done, What Next?

High school students face a difficult choice: pay to attend university, sign a declaration to obtain a scholarship or go abroad.

High school students face a difficult choice: pay to attend university, sign a declaration to obtain a scholarship or go abroad.

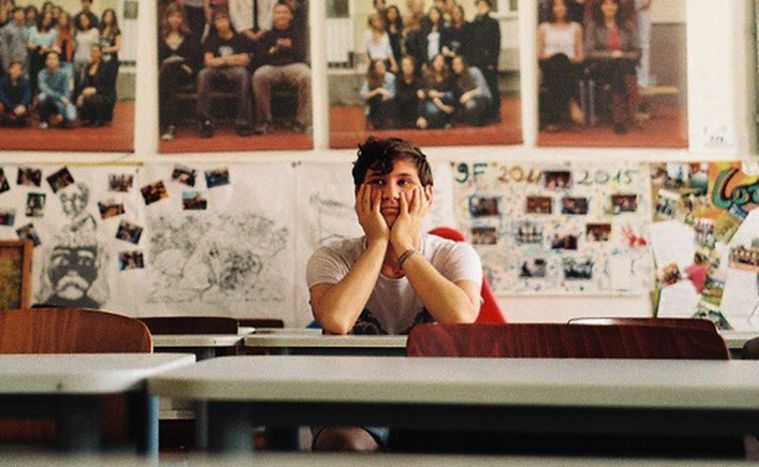

Márton is in the second year of high school. Before the reforms, he would have leaned towards studying media and communication; however, these options are on the list of 16 disciplines that are no longer eligible for government scholarships. He is currently developing a plan B, but says that he will not study something that does not interest him.

Márton is in the second year of high school. Before the reforms, he would have leaned towards studying media and communication; however, these options are on the list of 16 disciplines that are no longer eligible for government scholarships. He is currently developing a plan B, but says that he will not study something that does not interest him.

The state offers student loans, but not everyone wants to assume such a financial liability at the beginning of an academic career. Students pays an average of 4,000 euros for their undergraduate degrees. The unemployment rate among young Hungarians below 25 years old is 20%, while the average monthly salary is 492 euros. In light of such wages, earning 4,000 euros takes eight months, without considering other expenses.

The state offers student loans, but not everyone wants to assume such a financial liability at the beginning of an academic career. Students pays an average of 4,000 euros for their undergraduate degrees. The unemployment rate among young Hungarians below 25 years old is 20%, while the average monthly salary is 492 euros. In light of such wages, earning 4,000 euros takes eight months, without considering other expenses.

Images of Students

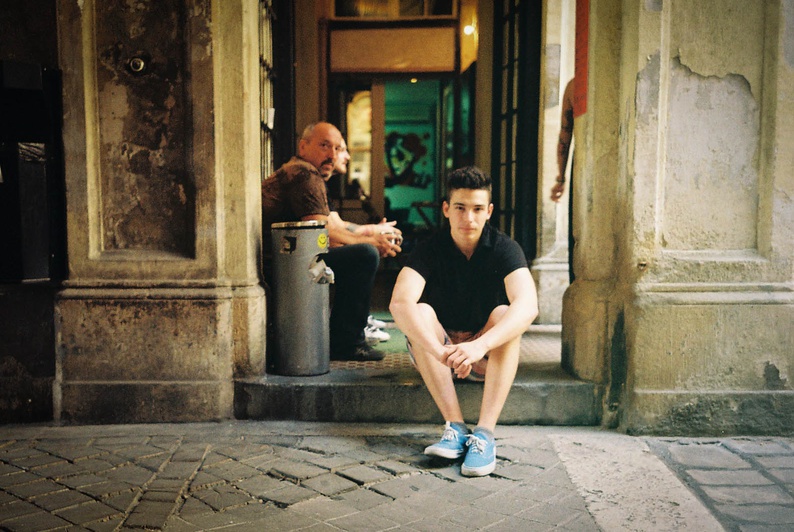

Peter managed to get one of the few scholarship places to study political science. He is from the generation that was first obliged to sign the declaration. According to his contract, after his undergraduate degree, he must work in Hungary for six years. He does not think it's a problem if he breaks the contract. If he doesn't keep the agreement, he could be forced to pay for his studies, but he doesn't care, as the fine would be equal to two months of his salary in western Europe, so he could pay it quickly.

Peter managed to get one of the few scholarship places to study political science. He is from the generation that was first obliged to sign the declaration. According to his contract, after his undergraduate degree, he must work in Hungary for six years. He does not think it's a problem if he breaks the contract. If he doesn't keep the agreement, he could be forced to pay for his studies, but he doesn't care, as the fine would be equal to two months of his salary in western Europe, so he could pay it quickly.

Anna, a student at Corvinus University, believes that the current condition — working in Hungary for as many years as you have studied (it used to be twice as long) — is a reasonable solution, as educated young people leave the country after graduating from the best universities.

Anna, a student at Corvinus University, believes that the current condition — working in Hungary for as many years as you have studied (it used to be twice as long) — is a reasonable solution, as educated young people leave the country after graduating from the best universities.

According to official statistics, one-quarter less students received a scholarship in 2012 than in 2011.

According to official statistics, one-quarter less students received a scholarship in 2012 than in 2011.

Németh is studying linguistics. She believes that if students are required to stay in the country, the state should also provide them with jobs. If she had to go to university now, she would probably go to Vienna, where higher education is free.

Németh is studying linguistics. She believes that if students are required to stay in the country, the state should also provide them with jobs. If she had to go to university now, she would probably go to Vienna, where higher education is free.

Eszter (right) is just finishing high school. She wants to go to England to study film. She would prefer to be in Budapest, but claims that Hungary does not invest in the film industry, making it difficult to find a job.

Eszter (right) is just finishing high school. She wants to go to England to study film. She would prefer to be in Budapest, but claims that Hungary does not invest in the film industry, making it difficult to find a job.

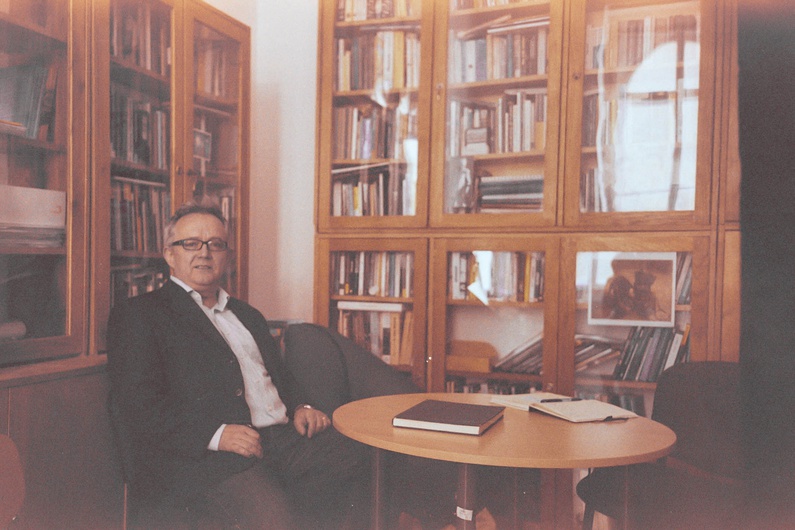

Professor Kovács of the Film Studies department claims that he knows nothing of the declarations signed by students or the financial cuts to higher education. When asked about the prospects of finding a job after graduation, he assures that his students have no problem.

Professor Kovács of the Film Studies department claims that he knows nothing of the declarations signed by students or the financial cuts to higher education. When asked about the prospects of finding a job after graduation, he assures that his students have no problem.

What are the results?

According to Dr Ferenc Hammer, a professor of sociology, the changes introduced by the government will widen the gap between rich and poor families. Wealthier students who do not wish to sign the declaration have the opportunity to go abroad, while the poor who cannot afford it, will take the scholarship and commit to stay in the country. One possible solution could be to introduce a small fee for every student.

The declaration, introduced by the Ministry of Human Resources chaired by Zoltán Baloga, constitutes a violation of European law on the freedom to choose one's profession.

The declaration, introduced by the Ministry of Human Resources chaired by Zoltán Baloga, constitutes a violation of European law on the freedom to choose one's profession.

Fidesz and Christian Democratic People's Party won twelve seats in the European elections. Their slogans were "More respect for Hungarians" and "Getting better in Hungary".

Fidesz and Christian Democratic People's Party won twelve seats in the European elections. Their slogans were "More respect for Hungarians" and "Getting better in Hungary".

Meanwhile, Hungarian students began using the word röghözkötés to describe their situation. It means to bound someone to a piece of land by tethering them to a pole in the ground.

Meanwhile, Hungarian students began using the word röghözkötés to describe their situation. It means to bound someone to a piece of land by tethering them to a pole in the ground.

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE DEDICATED TO BUDAPEST AND IS PART OF THE EU IN MOTION PROJECT INITIATED BY CAFÉBABEL WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION.

Translated from Budapeszt: wasza edukacja, moja emigracja