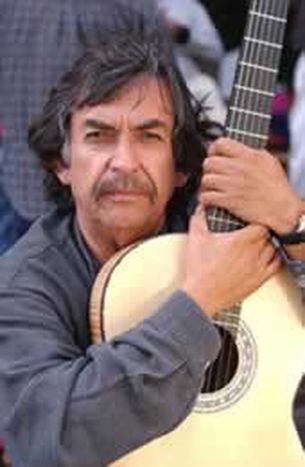

Ángel Parra: 'experiencing exile is painful - they push you towards an abyss'

Published on

Translation by:

kate stansfield

kate stansfield

Based in Paris for the past 35 years, the 64 year old musician son of folklore icon Violeta Parra on Chilean Septembers, exiles and his dead mother's legacy

We are in the Lumen theatre, after a concert in Brussels as a prelude to an upcoming Ángel Parra tour. At the end of two intimate hours spent transported by the songs of Violeta Parra – founder of Chilean folklore – the audience bids farewell to her son, whose voice and guitar have once again managed to pull his spectators out of the present and push them towards a catharsis bursting with nostalgia and celebrations. It is September, 'the most powerful month for Chileans,' Parra emphasises. The month in which, in 1810, Chile declared its independence from Spain; the month in which Salvador Allende rose to power in 1970 and when other powers evicted him in 1973.

Enriching exiles

Parra is also currently launching his third novel, Hands Behind The Head – in which he narrates, always with great humour, his dramatic experience during the first days following Pinochet's coup d'état in 1973. At the same time, he is already editing his fourth novel, which comes out in November. 'It is my way of recounting history: and what history can I tell if it isn’t the history of my people?'

It was Parra’s political connection with the left-wingers of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity that led to his imprisonment in 1973 in the National Stadium and Chacabuco concentration camp, following Pinochet's coup d'état. Later, in 1974, he found himself in exile in Mexico before ending up in Paris in 1976. 'To be able to live the present we must know where we come from. History weighs down on us considerably. When we escape all those experiences alive, we can consider ourselves privileged and reborn,' he explains when talking about his artistic relationship with the past.

Like so many others, Parra found himself in exile. 'The experience of exile is painful because it is an obligation, because they push you towards an abyss and you don’t know what’s going to happen to you. That’s what happened to thousands of people. It is unknown territory, a precipice, and you have to grab hold of whatever you can. For us, the welcome of the European natives, as I call them, has been fundamental. They are always very open to Latin Americans.'

'My case is exceptional because I fit in easily anywhere, but I try to speak not in my name but in that of the 1, 200,000 Chileans who had to leave the country,' he says, reflecting on the incomplete integration of Chileans abroad. 'Many people settled in with their packed suitcase under the bed, thinking of returning to Chile within a matter of days. However, 35 years have passed and there are people who have never returned and never will.' This anxiety about returning to Chile complicated the life of the exiles: 'They didn’t learn the local language, they didn’t become integrated, they worked purely to survive.'

Self-appointed messenger from a Chile still plagued with inequality

Parra now has a new Chilean tour planned. 'My life is that of a circus performer. Like the gypsies, I travel with my tent on my back.' In this coming and going, he lives up to his name: Ángel, the messenger. 'The work I do is like that of a postman: I carry news back and forth. When I go to Chile I meet people who were exiled in Berlin, in Brussels or in Paris and they ask after the people who still live in Europe. And viceversa - when I return to Europe, they ask after the people in Chile. My work is beautiful, full of personal relationships.'

When I ask him about the current political situation in Chile, he stresses the complex situation his country is experiencing. 'Even though democracy arrived seventeen years ago, Chile’s wealth is concentrated in 10% of the population - two million people live in extreme poverty.' Parra isn’t just standing back and doing nothing about this situation. 'In my modest role of communist militant, I do what I can by being there, I open my mouth when I can, because however much the socialist and demochristian companions are in power, they have got used to that power. They're used to the big cars with tinted windows, the secretaries, an entire system of privileges, and they have forgotten why they are there, what role they must fulfill,' laments a Parra who, however, considers it very positive that the current president of Chile is a woman (Michelle Bachelet). He hopes that she can bring about many changes in her remaining two years of office.

Legacy bearers

Along with his sister Isabel and the Violeta Parra Foundation, Parra has arranged to celebrate his mother’s 90th year between 4 October 2007 and the same day in 2008. It will be a whole year of festivities in different parts of the world. I ask Parra if he considers himself heir to his mother’s varied artistic legacy: 'Not only my sister and I but also the people of my generation; not only Chileans but also Argentinians, Peruvians or Bolivians are heirs to Violeta’s work, all Latin Americans,' he insists. In the light of his mother's vast accomplishments, Parra has come to ask if it is worth continuing to write songs. 'The repertoire we’ve inherited from Violeta Parra is so vast and so strong and of such quality. More than 300 songs, not to mention her unpublished works.'

The young Chilean singer Pedro Saavedra interprets The Tree, an Ángel Parra song

Translated from Ángel Parra: “sólo puedo cantar la historia de mi pueblo”