Tomasz Sobieraj: 'You don't have to write poems about shit, piss or hiccups'

Published on

Translation by:

Lydia BigosThe Polish writer is also a self-taught fine art photographer who exhibits in the UK, Germany, Austria and Spain. We talk about the problems of contemporary literature, how to resolve commercialism with art and how his home city of Łódź treats its artists

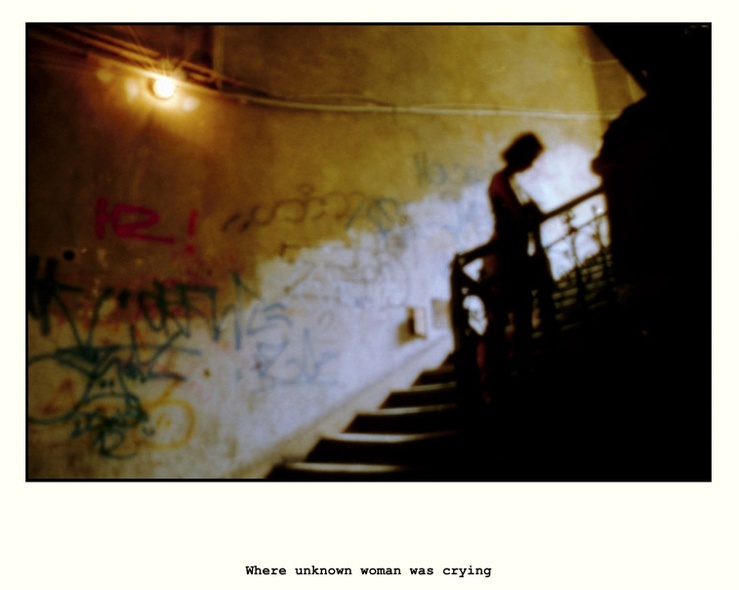

'It will only change the fact that there is now somewhere nice to go and have a cup of coffee in Łódź,' says Tomasz Sobieraj about the opening of the new Museum of Art, where we meet at the cafe Boston. It's located in the Manufaktura, a huge commmercial centre with shops, museums, restaurantsand cinemas, which was constructed partly in a former factory. His art is deeply inspired by the post-industrial nature of this city; it’s difficult to imagine some of his photo poems, like Enklawa ('Enclave') or Kolosalna morda miasta ('Colossal mug of the city'), coming from any other place. 'Łódź is a peculiar town. I'm very happy that I live here, it was a conscious decision to do so and I like it here.' However, does Łódź really have a lot to offer for an artist? Sobieraj bluntly replies: not completely. 'Unfortunately, in Łódź, the most important people are the ones that live in other countries. But maybe this is just a typical characteristic of Poland. You can put on any play if you are from Paris or New York.' Museums in Łódź, Sobieraj says, run away from new faces in the hunt for something safe and secure. There are only a handful of artists from Łódź who are constantly promoting themselves.

Age of convention

Sobieraj talks very quickly, is very expressive and always wears a big smile. We talk too about his love for coffee, the book that his wife has recently published, and at times, he interrupts himself to inform me he's going off record. As a writer, poet and photographer, it is difficult to define which artistic trait is most prominent. Sobieraj has had enough of the conservative outlook on photography. Some people have talent, like Mozart did. Others have to work hard, like Salieri. 'But you have to be Mozart, Salieri, Mickiewicz and Pushkin all at the same time,' he insists; be talented and work hard as an artist. As we talk, he often repeats the words of famous writers and philosophers that inspire him. Nor do you need to have the right degree to call yourself an artist, he adds, and Sobieraj knows what he is talking about; he is a geographer, hydrologist and climatologist by trade. During his time as a clerk - a 'good but slavish job', as he says on his website - he would hide the different pieces he wrote for himself, to impress himself with what he was capable of doing.

Sobieraj doesn't believe in artists only living on what they have created for themselves. ‘Everything costs money, and you need to live. I earn a living through commercial photography and from my poems or essays.'  Luckily, the commissions he receives - wedding photography, catalogue and calendar shoots - are not too time-consuming. Sobieraj likes to paraphrase Julian Tuwim, a poet from Łódź who believed that it was good practice to commit three to four working days per month to commercial work, to be able to do as you liked the rest of the time. Fortunately, his clients approach his portfolio and vision with common sense, and all parties are able to reach a satisfying compromise.

Luckily, the commissions he receives - wedding photography, catalogue and calendar shoots - are not too time-consuming. Sobieraj likes to paraphrase Julian Tuwim, a poet from Łódź who believed that it was good practice to commit three to four working days per month to commercial work, to be able to do as you liked the rest of the time. Fortunately, his clients approach his portfolio and vision with common sense, and all parties are able to reach a satisfying compromise.

Sobieraj the writer

Sobieraj’s opinion on contemporary literature and current popular trends are characterised by a lack of thought and aesthetic reversal, leading to his decision to publicise his works. 'I intend to stay adaptable, someone who converts literature according to their own path. I want logical thinking, aesthetics, the importance of words and philosophical reflection to be important again.' He is not fazed by the fact that his art is hermetic and far from popular culture; people prefer to consume than read a book. 'One in a thousand people read classical literature. Is it important? The only important thing is that people are happy. In the past only the elite could read, but the world is changing.'

'Philosophical reflection' and hermetecism are visible traits in his latest collection of stories, Dom nadzoru ('House Surveillance', Adam Marszałek publishing house). Polish critic Zygmund Herman has called it 'a new form in literature drawing freely from a variety of borderline epic genres.' Sobieraj’s stories are an extension of his own views on art; he believes that future generations will remember those who thought outside the box and were able to reach over and beyond the expectations set out for them, like Poland's Byron, Juliusz Słowacki. Writing differently has been a big advantage for Sobieraj. 'Art doesn’t have to escape from real life, but it also shouldn't be life,' he emphasies. 'You don't have to write poems about 'shit, piss or hiccups.' Sobieraj's next project is writing a national Polish poem full of public references and digression in poetic prose. It remains to be seen how it will work out.

'Philosophical reflection' and hermetecism are visible traits in his latest collection of stories, Dom nadzoru ('House Surveillance', Adam Marszałek publishing house). Polish critic Zygmund Herman has called it 'a new form in literature drawing freely from a variety of borderline epic genres.' Sobieraj’s stories are an extension of his own views on art; he believes that future generations will remember those who thought outside the box and were able to reach over and beyond the expectations set out for them, like Poland's Byron, Juliusz Słowacki. Writing differently has been a big advantage for Sobieraj. 'Art doesn’t have to escape from real life, but it also shouldn't be life,' he emphasies. 'You don't have to write poems about 'shit, piss or hiccups.' Sobieraj's next project is writing a national Polish poem full of public references and digression in poetic prose. It remains to be seen how it will work out.

Translated from Tomasz Sobieraj: „Trzeba być i Mozartem, i Salierim”