The parallel (and enigmatic) life of Russian cinema

Published on

Translation by:

Kate Stansfield

Kate Stansfield

Russia and its cinema are developing behind the EU's back. The films succeeding over there fail over here, and vice versa. Why? From Paris, a panel of experts decipher the unfathomable tastes of audiences on both sides of the former iron curtain over a screening of Pervyi Etazh (‘Ground Floor’)

The Forum of Images in Paris resembles the future imagined in the sixties: oval shapes, red lights, metal structures and staff with black-rimmed glasses. On 2 October a round table on the presence of Russian cinema in Europe is attended by five guest speakers in the presence of one film: Pervyi Etazh (‘Ground Floor’, 1990) by Igor Minaev. Sixty year-old married couples and single young people occupy the stalls. What brings them here on a Saturday afternoon? Russian culture has an enigmatic Dostoyevsky air: bony features, a prominent skull, thin beard and baldness. It is like The Battleship Potemkin (1925): a realist experience, focused and strident.

Russian cinema market today

Despite having more than twice as many inhabitants and twenty-five times the surface area, Russia has half the number of cinemas than France. But it wasn't always this way. ‘The soviet union had 300, 000 cinemas spread over its fifteen republics,’ says Joël Chapron, central and eastern European manager for distributor Unifrance. ‘Every small town, school or collective farm had a screen to project the latest communist propaganda. But the arrival of capitalism changed everything. Today, Russia's vast expanses make distribution so expensive that, for many producers, it isn't worth trying to reach the whole country, so the films never leave the confines of Moscow and St Petersburg.’

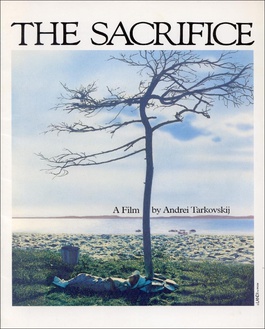

Like everything else in Russia, cinema grew up bound to the superpower of the state. Under Stalin there reigned an obsession with only producing mega-projects with unlimited budgets. After his death in 1953, the studios were decentralised and everything relaxed a little. Soon after, figures like the late Russian-Georgian director Mikhail Kalatozov or Andrei Tarkovsky appeared; the latter’s film The Sacrifice (1986) won two prizes at the Cannes international film festival of the same year.

Like everything else in Russia, cinema grew up bound to the superpower of the state. Under Stalin there reigned an obsession with only producing mega-projects with unlimited budgets. After his death in 1953, the studios were decentralised and everything relaxed a little. Soon after, figures like the late Russian-Georgian director Mikhail Kalatozov or Andrei Tarkovsky appeared; the latter’s film The Sacrifice (1986) won two prizes at the Cannes international film festival of the same year.

Today Russian producers are promoting commercial cinema with Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor, 2004) and Piter FM (2006) for example. Despite their local success though, they are not able to crack Europe. ‘We are talking about different cultures, different tastes,’ continues Joël Chapron. ‘It's like two parallel lives: films that succeed in the EU fail in Russia, and vice versa.’ Christel Vergeade, cultural attaché for the French embassy in Russia, adds: ‘Russian films don't take off in the European Union because here we tend to expect different subjects: the KGB, the mafia... There are certain preconceptions that are difficult to break: many people don't go to see Russian, Argentinian or German films because they are not used to hearing other languages, so many producers distribute trailers featuring not a single spoken word.’

The Ukrainian-born director Igor Minaev grabs the microphone to share his experience as a director at the end of the soviet era. He talks cheerfully, armed with some good anecdotes. ‘I worked in a small studio. It was almost like a family, but controlled. It was very difficult to develop good scripts, but we tried. Luckily, as we ran Cinemateca, we could get hold of foreign films now and again. I remember one time we conspired to see a French film. Quickly and silently, we shut ourselves in a room, and we put on the roll with trembling hands... That film was Emmanuelle (1973).’

The Ukrainian-born director Igor Minaev grabs the microphone to share his experience as a director at the end of the soviet era. He talks cheerfully, armed with some good anecdotes. ‘I worked in a small studio. It was almost like a family, but controlled. It was very difficult to develop good scripts, but we tried. Luckily, as we ran Cinemateca, we could get hold of foreign films now and again. I remember one time we conspired to see a French film. Quickly and silently, we shut ourselves in a room, and we put on the roll with trembling hands... That film was Emmanuelle (1973).’

The round table finishes as it began, in confusion: too many films, too many statistics, too many tastes... Silence. Ground Floor begins: a small Shakespearean tragedy dragged out of deepest, darkest Russia. Like Dostoyevsky’s face.

Images: main screenshot from Piter FM (2006) Robert Lesiak; The Sacrifice movie poster Andrei Tarkovski, 1986

Translated from La vida paralela (y enigmática) del cine ruso