The 'impossible' prisoner cum pizza boys of Naples

Published on

Imagine English young offenders in a 'social chippie', making fish and chips for the community to improve their self-perception and worth to society. In fact, this happens in Campania, where the cultural significance of family (and food) mixes with unconventional symbols of national identity, like rugby. Naples' crime backdrop stays taboo, though it's an important clue to understanding youth

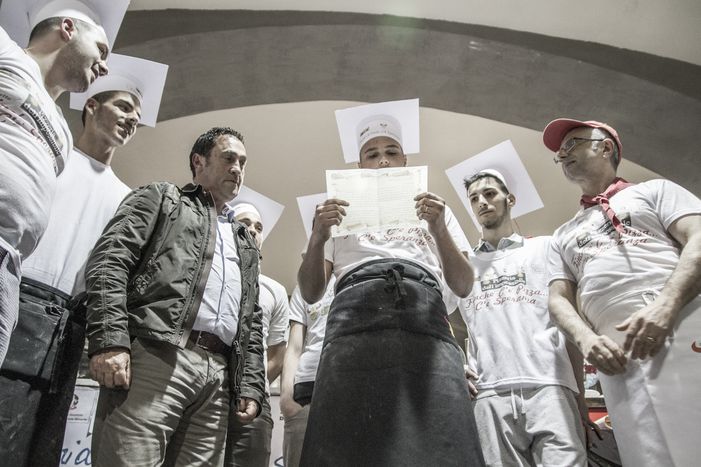

The young lads of the 'Pizzeria dell'Impossibile', decked out in white, are jostling with each other at their graduation ceremony and picking on my lack of Neapolitan. They have completed a 200 hour pizza-making training course over the last six weeks, which saw them churning out fifty free pizzas a day for disadvantaged members of the local community, who claim their meals with tickets given out via churches.

Yet these are no common trainees. These 14 boys have all been convicted of petty crimes and are on day leave from Nisida, home to one of Naples' main penal institute of minors, one of 17 in Italy. Located on an islet in the Mediterranean, the British army once used Nisida as a world war II-era prison; today, it also hosts the European observatory of juvenile crime.

Yet these are no common trainees. These 14 boys have all been convicted of petty crimes and are on day leave from Nisida, home to one of Naples' main penal institute of minors, one of 17 in Italy. Located on an islet in the Mediterranean, the British army once used Nisida as a world war II-era prison; today, it also hosts the European observatory of juvenile crime.

TASTE OF LEGALITY

'I'm a scugnizzo myself,' says Antonio Franco. 'I know about how difficult Naples can be.' He founded the Scugnizzi - aka 'Street Kids' - association in 2005, and has spent a decade working in juvenile rehabilitation, starting with informal activities such as football matches. In 2010, he created the 'If we have pizza, there is hope' scheme with the support of 'la Bufala brothers', a successful brand with Neapolitan roots who run a global chain of restaurants. No rent is due on this formerly empty building which has been renovated with bright yellow walls, just a short walk from the old city centre. The delinquents are usually hired after they are sentenced to Nisida. 'The state can’t give them such stability,' says Antonio.

This training cycle began on 4 February, with fifteen boys aged between 16 and 21. Ten are sent by the courts, whilst Olga Migliaccio, 27, selected five others who were living in more problematic areas of Naples. As a criminologist, the volunteer says that sometimes the approach is hard. ‘The boys don’t want a 'psychologist',' she says. 'The key is not to harbour prejudices, and to joke around with them.’ Around three weeks are devoted to the theory of pizza-making; 'such as why American pizza is not like Neaopolitan pizza,' says Antonio, with a knowing look.

This training cycle began on 4 February, with fifteen boys aged between 16 and 21. Ten are sent by the courts, whilst Olga Migliaccio, 27, selected five others who were living in more problematic areas of Naples. As a criminologist, the volunteer says that sometimes the approach is hard. ‘The boys don’t want a 'psychologist',' she says. 'The key is not to harbour prejudices, and to joke around with them.’ Around three weeks are devoted to the theory of pizza-making; 'such as why American pizza is not like Neaopolitan pizza,' says Antonio, with a knowing look.

In comes the daily delivery of a portion of desserts - the local specialty baba papa, Sicilian cannolo, sfogliatella. The interruption is almost divine, since the young baker responsible for such delights is Gennaro. The 23-year-old is upheld as the model of an integrated young trainee for the association. He lived in Nisida between the ages of 14 and 18, and is still working at a high-end bakery five years on, having successfully made the transition to employment and family values. Gennaro is one of three in the association's history to have done so. ‘Our aim is to try to get these lads out of Nisida before they return to their old ways,' emphasises Antonio. 'Having a job in Naples has always been a utopia; now it’s even harder.’

At the Casa Infante factory, we exchange elevator smiles with a young man, his fine eyebrows raised, a tattoo of a red kiss plastered on the right side of his neck. He smokes, inquisitively. Marco Infante returns, screams out ‘Gennaro!’, and leads the modest young man up the stairs before us. 'When I was young I made an error,' says Gennaro in the office of the Infante brothers, speaking quietly with a thick Neaopolitan accent; his hands and arms are also tattooed, and he wears a stud in his ear. ‘Education and values,’ interrupts Marco, as he sparks up a Marlboro red. 'They showed me the values of life,’ adds Gennaro, who works between 6am and lunchtime, before heading home to be with his two small children. ‘If you want to change something, it has to come from you,’ he says, simply. ‘The crisis hit Naples before it did everywhere else; you have to make your own possibilities.’

At the Casa Infante factory, we exchange elevator smiles with a young man, his fine eyebrows raised, a tattoo of a red kiss plastered on the right side of his neck. He smokes, inquisitively. Marco Infante returns, screams out ‘Gennaro!’, and leads the modest young man up the stairs before us. 'When I was young I made an error,' says Gennaro in the office of the Infante brothers, speaking quietly with a thick Neaopolitan accent; his hands and arms are also tattooed, and he wears a stud in his ear. ‘Education and values,’ interrupts Marco, as he sparks up a Marlboro red. 'They showed me the values of life,’ adds Gennaro, who works between 6am and lunchtime, before heading home to be with his two small children. ‘If you want to change something, it has to come from you,’ he says, simply. ‘The crisis hit Naples before it did everywhere else; you have to make your own possibilities.’

Is pizza the answer? ‘Naples is a poor city,’ explains Antonio. ‘Pizza is unifying, popular, everyone likes it. It’s very easy from an economic standpoint. And I knew the Bufala brothers.’ Daniele, 21, has just come back from working in Malta, and pipes in: 'It’s not important to make pizza. It’s about the social interaction.’

OVAL REDEMPTION

Rugby is another way to bond the young offenders within society. Initially, doubt was cast about the amount of physical contact the sport required by Nisida institute's director, Gianluca Guido. ‘The boys showed him that they could separate their detention from the field. It’s a good sport to exploit their energy, the mood,' says Marco Aiello, 26, outside the main stadium. The social worker has been captain of the 'Amatori Napoli' amateur rugby club for four years, coaching weekly games for eight to nine months a year. An average team is aged between 16 and 17 and is mixed with Italian and Roma youth, although Marco makes no distinctions with regards to the number of non-Italians.

In Naples, images of honorary citizen Diego Maradona grace almost every shop. Rugby is not such a cornerstone of Italian culture as football or pizza; Italy has only been part of the six nations since 2000. ‘The kids learn football on the streets. Everyone has their own rules; no-one knows rugby,' explains social worker Anna Ferraino about ‘la palla storta’ - ‘the strange shaped ball’. 'The youth is more spoilt today, but these guys aren’t used to a pat on the back,' adds Aiello. 'There’s no code of affection or compliments. They don’t see you as a god or an authority, but a brother. Getting their respect is not so hard.' Anna adds: 'The main problems we see are inside the centre, with its structure and building.’

Aiello says that some openly criticise this alternative rehabilitation, asking if the boys are in school or holiday. 'The most important thing is belonging to a group,' says Anna. 'It’s an intellectual capacity, far better than the classroom.' She points out that it’s the ‘after’ which counts, and touches on the topic of the Camorra. 'Some of these kids have ties to the criminal families,' she says. 'Social workers aren’t allowed to have any more contact with them after they leave.' The juvenile detention rate in Italy is low compared to the rest of Europe, since the justice system is characterised by leniency, perhaps due to the simultaneously catholic and criminal societies these children are being raised in. Re-offending rates in Italy are also low on a European level, compared to, say, the UK.

Back at the pizzeria, Antonio Brigida is hugged by his parents, Filimena and Aliberto, and an emotional Antonio Franco, who is set to receive his next 'batch' of troubled boys next Monday. ‘I’m sad. The course is finished. I would like to be a pizzaiolo,’ says 16-year-old Antonio. The ‘impossible’ he has experienced outside of his coastal prison defines the utopian, spontaneous determination of Naples.

Back at the pizzeria, Antonio Brigida is hugged by his parents, Filimena and Aliberto, and an emotional Antonio Franco, who is set to receive his next 'batch' of troubled boys next Monday. ‘I’m sad. The course is finished. I would like to be a pizzaiolo,’ says 16-year-old Antonio. The ‘impossible’ he has experienced outside of his coastal prison defines the utopian, spontaneous determination of Naples.

Thanks to Francesco Raiola, Giorgio Mennella, and especially Antonio Alfano and the invaluable Mario Paciolla and his team, our hosts, at cafebabel Naples

This is the fourth in a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind

This is the fourth in a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind