Serb elections: blackmail Europe

Published on

Translation by:

Alison MatthewsSerb incumbent Boris Tadic needs every vote he can get in the second round of presidential elections on 3 February. PM Kostunica supports his pro-European coalition partner - but on his own terms only

Serbian prime minister Vojislav Kostunica is trying to blackmail pro-European presidential candidate and current incumbent Boris Tadic. Kostunica will only support his coalition partner in the second ballot if he gives up his increasingly pro-European agenda. Tadic has so far dismissed this demand. Critics warn that Kostunica will attempt to form a coalition with the ultranationalist radicals instead.

Kostunica’s nationalist-conservative Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) has suggested that Tadic’s pro-Western Democratic Party (DS) alter the existing coalition agreement. This agreement states that Serbia is ready to sign the drafted EU stabilization and association agreements (SAA). However, the text also commits the Serbian government to immediately invalidate the SAA if the EU carries out their planned civil mission in Kosovo and breaches the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) agreement.

Kosovo Independence? No way

All coalition partners oppose Kosovo’s independence and share the view that the deployment of an EU mission requires a decision by the UN Security council. However, Tadic’s DS party isn’t prepared to let the Kosovo argument affect Serbia’s chances for European integration, which is exactly what Kostunica is demanding.

Elections streets in Serbia (Foto: davorko [loves konjikusic.com]/ flickr)

Elections streets in Serbia (Foto: davorko [loves konjikusic.com]/ flickr)

This means that Boris Tadic is now faced with a dilemma: if he wants to win the expected neck-and-neck race on 3 February against ultranationalist Tomislav Nikolic of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), he needs the support of the increasingly euro-sceptic prime minister Vojislav Kostunica. According to data from the Independent Centre for Free Elections and Democracy (CeSID), Tadic won 35.4 percent of the vote in the first elections on the 20th of January 2008, while Nikolic won 39.4 percent.

If Tadic does agree to the suggested changes to the coalition agreement, he risks scaring off would-be voters, most importantly those from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the small, pro-Western opposition party led by Cedomir Javanovic. He is dependent on them for an election victory. He needs to show his own voters and EU politicians in Brussels that he is serious about a fast approach to Serbia joining the EU. Tadic has suggested that the presidential election is more like a referendum for or against the EU. He warns that the election of Nikolic would mean a return to the shadows of the 90s under Slobodan Milosevic.

'No alternative to Europe'

Tadic is fully aware of the difficulty of this situation. He is leaving no-one in any doubt about his pro-European commitments. Without directly mentioning Kostunica’s blackmail attempt, he said at an election speech, 'I will not allow anybody to set conditions for Serbia's European future and for the future of our children. There is no alternative to Europe.'

This is why political observers don’t think that Tadic will agree to Kostunica’s offer. The president needs to make a decision, Marko Blagojevic of the non-governmental centre for free speech and democracy (CeSID) tells the Beta news agency. And it is only logical for him to 'appease his pro-European target group.'

Tadic’s opponent doesn’t just object to an affiliation with Europe on principle; he also favours a closer partnership with Moscow. In this respect, he is on the same wavelength as PM Kostunica, described as a 'Russophile' by The Economist’s Belgrade economic expert Misa Brkic.

Tadic’s opponent doesn’t just object to an affiliation with Europe on principle; he also favours a closer partnership with Moscow. In this respect, he is on the same wavelength as PM Kostunica, described as a 'Russophile' by The Economist’s Belgrade economic expert Misa Brkic.

Parliamentary delegate Nenad Canak, whose small, pro-Western 'League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina' is supported by Tadic, accused Kostunica of acting against his coalition partner and attempting to dissolve government. It is obvious that the DSS 'want to form a coalition government with the radicals,' said radio programme B92. The goal of this coalition would be to 'trade a civilised world for one supported by Russia.'

On 25 January 2008, Serbian infrastructure minister Velimir Ilic signed a billion dollar energy agreement between Russia and Serbia in the presence of Tadic, Kostunica and President Putin. The two countries agreed on the building of the gas pipeline 'South Stream' through Serbia by the Russian gas monopoly Gazprom. In return, Russia now owns the majority of the Serbian gas company, NIS, which was formerly controlled by the Serbian government. This has strengthened Russia’s influence in the European energy market. Critics accuse the Serbian government of selling NIS at far too low a price as a way of thanking Russia for its support in the Kosovo conflict.

The author is a member of the German writers network n-ost

Serbia: a nation in conflict

All eyes are on Serbia. And within the country the feeling of historic injustice is growing. With nationalist sentiment becoming ever more radical, is this the breeding ground for the next disaster?

Since the war that led to the break-up of Yugoslavia, labelled by the mass media as 'the Balkans', the Serbs have been seen as the 'last barbarians in Europe.' Consequently, when the question of Kosovo arose again, the Western media announced renewed radicalism in Serbia.

The incumbent president, pro-European democrat Boris Tadic, who remains inflexible as regards Kosovo, was defeated by ultranationalist Radical Party candidate, Tomislav Nikoli in the first round of the election voter turnout (reaching only 61%).

Since the end of the bloody war of 1992-1995, Serbs have not readily spoken out about public matters. On three occasions during previous presidential elections, low turnout at the ballot box prevented a head of state from being elected. However, the current elections are happening at a particularly significant time for the destiny of the Serbian nation, whose cradle, Kosovo, is inhabited for the most part by Albanians. The country finds itself at a fork in the road: on one side the west, with NATO and the EU, and on the other the east, side by side with their former ally, Russia.

In this situation the EU sees Slovenia as the negotiator. However, Slovenia enjoys neither popularity nor respect within Serbia. The attempts to move the country towards a peaceful resolution regarding Kosovo have not been successful. What the European Union is calling a 'necessary compromise' with the Albanians residing in the province, is seen by Serbia as pressure from Brussels (and the USA) in the light of Belgrade’s European aspirations. It is seen as renouncing the country’s sovereignty and territorial unity.

'How is it possible to force a democratic country to give up part of its territory?' asked prime minister Kostunica addressing the UN Security Council.

'How is it possible?' asks civilian Europe in the face of the extermination of countless people and the war crimes which accompanied the break-up of Yugoslavia?

'How is it possible?' is what the population of Belgrade asked themselves in 1999 when NATO bombs were exploding around them.

They did not accept this 'undeserved' punishment and now they do not want to hear about the 'reward they deserve.' It seems that EU entry is to be seen by the Serbs as a reward, in exchange for renouncing a part of their territory to their 'sworn enemy,' the Albanians.

So who will be surprised this time at the outcome of the negotiations? Who will be the one asking 'how is it possible?' And above all, who will answer this question?

Translated from Italian by Alison Matthews

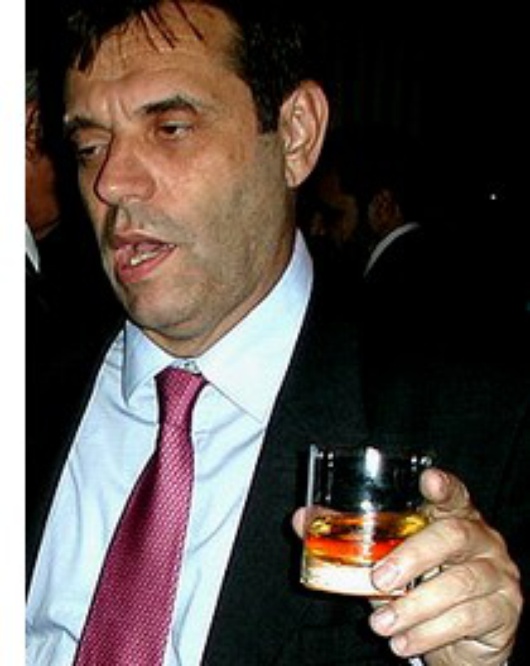

Photos: Kostunica looking a bit worse for wear (in-text: Viktor Sekularac/ Flickr), Elections streets in Serbia (In-text and homepage: davorko [loves konjikusic.com]/ Flickr)

Translated from Serbien: Kostunica will Tadic mit Europa erpressen