'Prishtinali': urban faces in a raw capital

Published on

A capital in transition has ‘bigger’ priorities than music and fashion. Dynamic young patriots use these elements of renewal to bring their city closer to Europe

During the Kosovo war, radio station Kontakt tried to 'resuscitate Pristina's urban identity' which it felt had been 'lost' in the crisis between the co-habiting Serbs and Albanians. 'By reminding this very old city - with its identifiable way of life - of its urbanity, we could spur those who ignore each other in the street, to renew their contacts.’ Founder Zvonko Tarle's open letter to Yugoslavia's president, Slobodan Miloševi, was in vain. The multiethnic station was closed down after ten days in 1998.

Folk FM

Today, Pristina has a new 'identifiable way of life' centering around the 'Prishtinali', the city's residents, especially after a new alternative, digital radio station started redefining the city's post-war urbanity in 1999. 'I felt like shit when I came back, although everyone was happy to see each other again,’ explains Dardan Islami, 34, co-founder of Kosovo’s Radio Urban FM and Spray Club. A 100% Serb capital, emptied during the war, went on to be reinhabited by 200, 000 village newcomers. 'They killed the balance,' Islami damns, in his Godfatheresque voice. 'We lost our identity in 24 hours with their folk music and way of living; it was very different from what we know.'

'We lost our identity in 24 hours with folk music'

Urban FM disturbed 'peasant Pristina' with its rock music and non-commercial electronic music. 90% of the latter comes from London, thanks to Islami’s time ‘living life in the fast lane’ as one of west London’s top five barmen (as he was voted in 2006). 'Sticking to an alternative, live format was difficult,' he remembers, of a scene which featured the state-owned Radio Pristina and smaller fellow inexperienced radio stations. Six months, an antenna and transmitter later, Urban FM caught word of mouth. After 9/11 they got hold of their own generator to translate CNN news to the crowds. In 2002 they boarded a 'love train' with multiethnic DJs to trace refugee routes to the Macedonian and Serb borders. With 200, 000 listeners by 2004, in 2006 the team went national, covering 70% of Kosovar territory. Today, it has a staff of eleven and an average age of 23.

Meeting the Prishtinali

Mobile phone lights shine out of one of the downstairs windows of the run down house where Urban FM broadcasts from. The live show, one of five a day, is cancelled tonight due to the power cut. Drivetime presenter and EU youth programme member, Barth Shkreli, 23, and DJ Strella lead us upstairs by candlelight. A fish tank embeds a wall separating the studio, with its spectacular night view of the hills.

The DJs become my Pristina-by-night hosts. A stroke of luck for the spoilt westerner that I am; no real city maps exist here, let alone city listings guides. Jhum, 25, tells me that if one of these existed, he would never advertise 'Tusks' bar off the Mother Teresa boulevard which he co-owns, fearing those dreaded 'peasants' who would filter in from outside the city. At another local, the DJs jokingly introduce me to the ‘president’s daughter’, Rea, daughter of Veton Surroi, who is ironically soon-to-be former leader of the Ora reformist party. Scoop: Dardan Islami has just left Urban FM to run for Ora.

The DJs become my Pristina-by-night hosts. A stroke of luck for the spoilt westerner that I am; no real city maps exist here, let alone city listings guides. Jhum, 25, tells me that if one of these existed, he would never advertise 'Tusks' bar off the Mother Teresa boulevard which he co-owns, fearing those dreaded 'peasants' who would filter in from outside the city. At another local, the DJs jokingly introduce me to the ‘president’s daughter’, Rea, daughter of Veton Surroi, who is ironically soon-to-be former leader of the Ora reformist party. Scoop: Dardan Islami has just left Urban FM to run for Ora.

Capital of a state in which 50% of youth are under 25

At a shisha café later that night, the boys poke fun at him for being election number '69'. Ora poll last in the 17 November local elections, prompting Surroi's resignation, although in the 2006 Human Development UNDP report, 81.4% of youth had pledged to vote. Islami remains firm about being a voice for an urban youth in politics, in a region which 'has moved a step closer because of the question of a political status. These kids have every right to be Europeans.'

'The majority are students who get shit education and job prospects'

Kosovo has Europe's youngest population, according to the same 2006 UNDP report. 21% are aged between 15 - 25, and over 50% of the population is under 25. ‘People today are 23, 24, 25. Think where they were eight years ago. Born in a state of emergency, they experienced war at thirteen and fourteen, left to live in refugee camps and returned in 1999. Nice kids, compared to the times they were brought up in. The majority are students who get shit education and job prospects. And 99% speak English which is strange - many have never lived abroad,' remarks Islami. 75% of Kosovo's population use the internet. 'They're very pro-western,' Islami goes on. ‘They're into music, MTV, movies and there's a certain fashion influence from European trends.’

Fashioning a ‘now’

Enkeleida Shatri, 32, came to Kosovo after the war in 2000. Thanks to her Kosovar doctor husband’s private funding - ‘it’s a bit difficult for a woman to have her own business here’ – her three-year old Akademia Evolucion (Evolution Art and Fashion Institute) will launch Pristina’s first generation of designers when the class of 2005 graduate in summer 2008. On offer: BA degrees in painting, fashion and interior design. In a move with eyes open to Europe, in March 2008 final year students will enjoy the first study exchange partnership to the Institute di Moda Burgo in Milan. ‘A little problem,’ the former Miss Albania contestant frowns, ‘is that the standards of our 51 students are not the same.’

Enkeleida Shatri, 32, came to Kosovo after the war in 2000. Thanks to her Kosovar doctor husband’s private funding - ‘it’s a bit difficult for a woman to have her own business here’ – her three-year old Akademia Evolucion (Evolution Art and Fashion Institute) will launch Pristina’s first generation of designers when the class of 2005 graduate in summer 2008. On offer: BA degrees in painting, fashion and interior design. In a move with eyes open to Europe, in March 2008 final year students will enjoy the first study exchange partnership to the Institute di Moda Burgo in Milan. ‘A little problem,’ the former Miss Albania contestant frowns, ‘is that the standards of our 51 students are not the same.’

Valdrin Sahiti, a third year Prishtinali, is the only male student in his year. The only other is in Italy studying industrial design. 'But this year two more guys will come,' his fellow students chime. Valdrin, 21, smiles when I ask if his first degree in economics and finance degree is more acceptable in a society rooted in patriarchy, despite its evident alternative identity. ‘We have bigger priorities than fashion and art. But we’ll have good careers because Kosovo doesn’t have any good fashion designers. We must do the best for our country.’ ‘It’s the right time and place to work on this now,’ adds Enkeleida. ‘Why leave? We’re not so far from European fashion. People shop, we have Zara and Mango, they watch TV. There was nothing here after the war, so how would we have a culture rooted in fashion?’

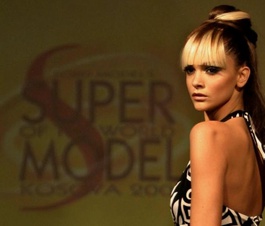

Supermodel, super state

Dhurata Lipovica, 19, waits outside Fama hair salon, her tall figure looming on the rainy, darkening street. After winning a competition to go to New York and be the first Miss Kosovo in the Ford supermodel of the world contest in January 2007, Dhurata prioritised her family, studies – and Kosovo. She was ten during the war, didn’t vote in the 17 November local elections and has never thought about whether she was European ‘because I have never been asked!’ At times she found it tricky to explain where Kosovo was when she was in America. ‘I couldn’t say near Serbia. And no-one knew Albania - but they knew Italy.’

Dhurata Lipovica, 19, waits outside Fama hair salon, her tall figure looming on the rainy, darkening street. After winning a competition to go to New York and be the first Miss Kosovo in the Ford supermodel of the world contest in January 2007, Dhurata prioritised her family, studies – and Kosovo. She was ten during the war, didn’t vote in the 17 November local elections and has never thought about whether she was European ‘because I have never been asked!’ At times she found it tricky to explain where Kosovo was when she was in America. ‘I couldn’t say near Serbia. And no-one knew Albania - but they knew Italy.’

The fashion scene is held back by a lack of resources and family-focused attitudes, the young Prishtinali supermodel reveals. ‘Models usually tell stylists what to do. We need lecturers - we have so much potential but not enough experience. There are no real fashion magazines, no male models. It’s not cool for boys. One left to work in Greece; models are paid so much better there. When an eighteen year old female model friend of mine got a call for Italy, but her father didn’t let her go. Here, you live with your parents until you’re 25.’ She hopes attitudes will loosen up for models to wear bikinis freely in shoots. ‘If we want to be with the Europeans, we have to change.’ The business management student at the American University of Kosovo plans to use her thesis – and her American training, her only external experience - to set up her own agency offering training, unlike agencies here like ‘Tram’, which find models jobs. ‘If we achieve changing the mentality here, we will be a great country in the future, even though we are great now. We will make Pristina look like New York.’

Many, many thanks to Flora Loshi