Prépas Classes, a French trait?

Published on

Translation by:

Maria-Christina DoulamiBe it science, literature or business, these special classes prepare students for the entrance exams of the prestigious French "Grandes écoles". Uniquely, these prep classes have managed to attract the attention of several countries, from China to Brazil.

The Bologna Declaration (19 June 1999) led to a harmonization of the higher education system across Europe. This apparatus, which redesigned the European higher education sector, introduced a system of academic credits - ECTS (European Credit Transfer System and Accumulation) - structured in three cycles: Three-year, Master's and Doctoral degrees.

In a European framework that promotes a system of higher education in the pursuit of greater compatibility between Member States, the unique French educational model, includes certain exceptions: the PCGE or "Preparatory Classes for the Grandes écoles”, which, even today, have a special status and remain a hotly debated topic.

Scientific, literary or business preparatory classes, called "prépas classes" or simply "prépas," train students for the particularly selective admissions process of the prestigious French "Grandes écoles" (École Polytechnique, École Centrale, HEC, ENS, to name a few). The prépas are considered to be an integral part of higher education admissions, and even today, for two to three years, they form a part of the most important high schools across the France.

A bit of history

The creation of this educational apparatus dates back to post-revolutionary France in the late eighteenth century. It was precisely the French Revolution that created the Écoles spéciales to provide training for the military and technical elites of the nation.

Before 1789, admission to centres of excellence, such as the renowned École Polytechnique and École Normale Supérieure (both founded in 1794), was determined by birth. An emblem of the Republican merit system, the establishment of a system of national competitions, with the consequent introduction of the merit criterion, unhinged the foundation of the society of the Ancien Regime. This democratised the selection of elites. Under the Third Republic, between 1880 and 1914, the system of scientific preparatory classes later took shape and would remain almost unchanged until 1970.

The history of literary and business preparatory classes is, however, more recent. It is in 1880 that in some high schools higher rhetoric classes were set up, as part of the preparation for the École Normale Superieure (ENS) competition. After the war, the merit principle was extended to all administrative and economic careers, with the creation of the ENA (École Nationale d'Administration) and the business “Grandes écoles”. Eventually, in the sixties, it led to the creation of the system of "Grandes écoles", with many associated preparatory classes still in force today.

However, it was only in the 70s, in particular, that the business prépas HEC (École des hautes études commerciales) multiplied, and witnessed a dramatic growth since the 80s [1].

And today?

The reputation of the prépas classes remains intact and is still today the "voie royale" ("royal path") to be allowed into the most prestigious schools.

A selection tool of the French elite, there is no longer a unanimous postive view towards these preparatory classes. A range of voices have questioned the effectiveness and, above all, legitimacy in a context where social disparities are strongly evident.

A selection tool of the French elite, there is no longer a unanimous postive view towards these preparatory classes. A range of voices have questioned the effectiveness and, above all, legitimacy in a context where social disparities are strongly evident.

If prépas students are mostly selected from the ranks of the children of the country’s executives, intellectuals and teachers, there ought to be efforts to democratize the system. That would lead to a movement of "diversification of access paths to the “Grandes écoles”, which could, according to Claude Lelièvre, a specialist in the history of the French education system and Professor Emeritus of History of Education at the Sorbonne (Paris V), threaten the long-term future of the PCGE.

For the moment, however, the statistics confirm a stable trend: the total number of students (8% of all students) who attend the prépas classes each year in France, 80% successfully pass the entrance examination to enter the selected school.

A French trait exportable to the world?

A Franco-French system (metropolitan France and overseas communities, Dom-Tom) par excellence, the PCGE has no equivalent elsewhere in the world, except for some French high schools offering their students the opportunity to attend prépas classes, including the Lycée Descartes in Rabat in Morocco or the Lycée Français in Vienna, Austria.

"At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the system (the PCGE) aroused a certain admiration everywhere in Europe. Schools such as the École polytechnique or the École Central served as a model and have been imitated in many countries, including the United States," says Bruno Belhoste, historical specialist at the Université Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne.

This structure of universities, however, has gradually prevailed and in Europe, as elsewhere in the world, the university system is now predominant. In the US, for example, the Engineering Schools and Business Schools have a statute similar in all respects to that of the universities. This is the case not only in the United States, but also in England, where the formation of local elites passes through the mesh of high school and college selection.

As elsewhere in Europe, education in the United Kingdom is based on a single model with regard to England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Scotland, instead, has its own order system. University courses last three years and result in the Bachelor of Arts (BA) or the Bachelor of Science (BSc). That can be followed by a Master’s degree, which lasts from one to two years, and a three-year Doctoral dissertation, which includes a final thesis.

In other examples, Italian high schools, like those in Germany, are mostly designed as preparation for university. However, unlike Germany, any secondary education in Italy allows access to primary level university studies. To enter a German university, it is not necessary to have the ''Abitur"(diploma from the "Gymnasium" or the higher one from the "Gesamtschule"). This condition, however, was partly dropped in 2009.

In Spain, high school has a duration of three years (from 16 to 18 years old), with the possibility of an optional year for college preparation. In Portugal, secondary school courses last three years (ranging from 15 to 18 years old) and are divided into two types: courses mainly oriented to the continuation of studies (CSPOEPE) or general and technological courses (CT), which prepare for professional life.

Greece too, made great efforts from the seventies to modernize its education system, and has complied with the European model. The selection of higher education in Switzerland also consists of two main options, high schools and higher vocational education. Elsewhere, the higher education systems of the Scandinavian countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden) are also comparable to those of other European countries.

The case of the École Centrale de Pekin

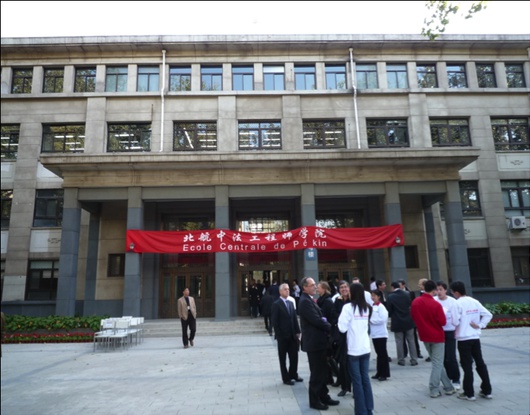

A recent case of exporting the PCGE model outside Europe is represented by the École Centrale de Pekin, which in six years prepares trilingual (Chinese, French, English) high-level engineers. Created in 2005 by a Franco-Chinese partnership, the École Centrale de Pekin, affiliated to the group of French Écoles Centrales (Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Paris), is the first engineering "Grande école" francophone in China. Students undergo a year of learning the language, two years of prépas - integrated - before tackling the three remaining years. Currently attended by 672 students, it has produced its first graduates in 2012.

A recent case of exporting the PCGE model outside Europe is represented by the École Centrale de Pekin, which in six years prepares trilingual (Chinese, French, English) high-level engineers. Created in 2005 by a Franco-Chinese partnership, the École Centrale de Pekin, affiliated to the group of French Écoles Centrales (Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Paris), is the first engineering "Grande école" francophone in China. Students undergo a year of learning the language, two years of prépas - integrated - before tackling the three remaining years. Currently attended by 672 students, it has produced its first graduates in 2012.

So, does this apparatus of international cooperation, which combines the multiple interests of governments and French companies, open the way for other similar experiments? After Beijing, Centrale Paris has exported its model to India where, in September 2014, a campus was opened in partnership with the Indian group Mahindra. Another partnership will be launched in Casablanca, Morocco. And other countries, such as Brazil, are vying among possible new openings.

"The careers of engineers that evolve exclusively in France no longer have reasons of existence. Our graduates have a global vocation. This implies that our students can immerse themselves in diverse cultural contexts. The international opening is now a necessity. Schools must adapt to that reality," says Hervé Biausser, Director of Centrale Paris.

Are we witnessing the beginning of the globalized - "French" – training of planet’s elites? France, exporting its model, can only hope so.

Notes

[1] The intervention of Bruno Belhoste, historical specialist at the Université Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne, the Colloque UPS (May 2003), offers a complete and accurate view of the history of the prépas class, is available (in French) here.

Read here the second part of our investigation on the prépas classes in France.

Translated from Classi prépas, un’eccezione francese?