Post-dictatorship Spanish TV: 20 years after Crystal Ball

Published on

Translation by:

Jessie L.‘I adore the economy, capital gain and dysentery!’ chanted an ‘ugly, evil and electrocuting’ puppet with bulging eyes and cables for hair. Bruja Avería (Breakdown Witch) was the wicked witch from the legendary eighties programme. It's been off-air for over twenty years, but audiences are still shocked by its brashness

Laugh, Sir, and the television you will break. Laugh, Madam, and a broken washing machine you will make.

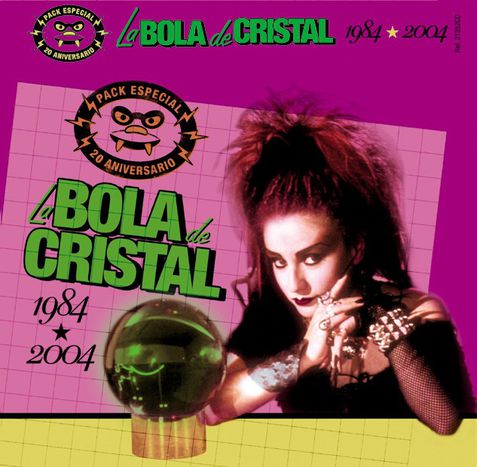

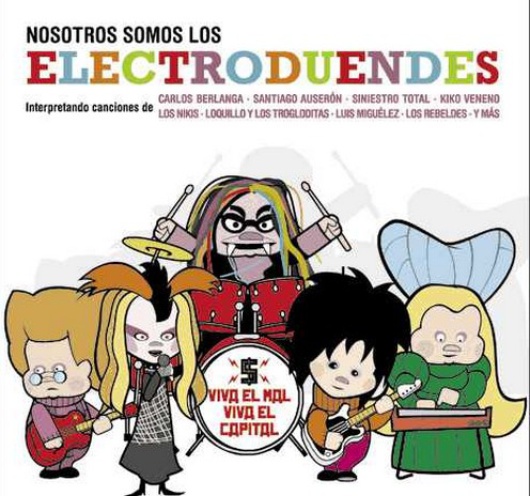

The Crystal Ball ('La Bola de Cristal') was created by director-journalist Lolo Rico and launched in 1984 with the aim of appealing to children of all ages. Each of its four segments (which changed and evolved over the years) targeted a different age group. For the youngest children, there were The Electrogoblins (‘Los Electroduendes’), involving puppets; The Bookviewer(‘El librovisor’) attempted to encourage older children to read; The Magnetic Strip (‘La banda magnética’) was about film and television; and lastly, there was a news programme for young people called The Fourth Part(‘La cuarta parte’) , which was initially shown independently from the rest.

Its child-oriented content soon gave way to much more analytical subject matter, with higher social, cultural and political bearing. Even the show's director has pointed out on various occasions that The Crystal Ball wasn't just for children. Francisco Quintanar, a researcher for the programme since its beginnings, agrees. ‘Nobody in this day and age would put The Fourth Part on children's TV,’ he tells us over the phone, referring to the segment presented by former singer Javier Gurruchaga which covered current events such as apartheid in South Africa and censorship; ‘That stuff is something for prime-time viewing.’

The Crystal Ball reflected the changes taking place throughout Spanish society during the country's transition to democracy. After forty years of dictatorship, there was now guaranteed political amnesty and free press, trade unions and the right to strike were legalised (1977), as was divorce (1981) and laws against adultery were done away with (1978).

The Crystal Ball reflected the changes taking place throughout Spanish society during the country's transition to democracy. After forty years of dictatorship, there was now guaranteed political amnesty and free press, trade unions and the right to strike were legalised (1977), as was divorce (1981) and laws against adultery were done away with (1978).

On the streets, there was a new air of tolerance which nurtured breakthrough socio-cultural movements such as La Movida madrilène ('The Madrilenian groove'). La Movida was epitomised by figures like filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, photographer García Alix and singer and presenter of The Crystal Ball, Alaska, daughter of an exiled Spanish republican soldier and a female exile from the Castro regime. According to Quintanar, this era was vital to the creation of the programme. At that time, he explains, television in Spain was enjoying more liberty in regard to content than ever before, due to various factors. Firstly, a new government had been democratically elected and had to live up to its democratic status by not interfering in broadcasting. Secondly, the repercussions of censorship under the dictatorship had left a distinct void in Spanish television. ‘However,’ adds Carlos Fernández Liria, one of the programme's writers, ‘we have to avoid glamorising the era.’

If I at least had a television, I could maybe put up with exploitation -one of the sayings from the show

Describing The Crystal Ball as 'politically incorrect' is an understatement. ‘It was terrorism,’ jokes Quintanar. Writer and philosopher Fernández Liria confirms that the team had a carte blanche when it came to writing. Only on very few occasions did they receive any warnings ‘from the US embassy or the Iranian one, for criticism of Ronald Reagan or Ayatollah Khomeini, for example.’

One aspect of the programme that Fernández Liria makes sure to draw our attention to is the political nature of the electrogoblins - those ‘goblins of electronics’ who made fun of those ‘dimwatt humanoids’. He tells us that in one series, the electrogoblins went through, chapter by chapter, the first volume of Das Kapital ('Capital', 1867). Fernández Liria highlights the work of his colleague Santiago Alba Rico in explaining marxism and the economy to children - it allowed them to ‘break new ground and talk about something different for a change.’

But beyond the political element, audiences today are still astounded by the insolent and crass tone of the programme. For example, one part gave advice on how to ‘not lose one's dignity during meals’ by ‘energetically protesting about dishes that you don't like’, ‘throwing balls of bread at your little brother’ or, of course, ‘always wiping your mouth with your sleeve.’ In another part, a girl gave children an educational explanation of her pregnancy: ‘I've got a humanoid growing inside me now because my boyfriend and I had sexual relations, of course.’ In a third part, children were given fifteen seconds to imagine something: ‘If you haven't thought of anything yet, maybe you should watch less TV.’

Even though this programme is responsible for ‘making La Movida fashionable,’ it is necessary to avoid making a complete association between the two. It's true that The Crystal Ball is aesthetically similar to and influenced by many of the protagonists of La Movida. However, the programme wasn't broadcast until the mid eighties, as the movement took its dying breaths, and it finished at the end of the decade, within a radically different social and cultural context. The actual programme, in turn, distances itself from La Movida by offering an open commentary on the subject in some of its episodes.

‘The only place you could show something like that again is the web’

Fernández Liria concludes by reflecting about the impossibility of showing a programme like The Crystal Ball on today's commercial television. Quintanar seconds it: ‘The only place you could show something like that again is probably the internet.’

First published on cafebabel.com on 23 January 2009

Translated from La Bola de Cristal y la Movida: ¡Viva el mal, viva el capital!