Photos: Prague Spring, forty years on

Published on

Translation by:

Nabeelah ShabbirOn 21 August Prague commemorated forty years of it’s famous democratic ‘spring’, which ended revolt in the capital this past century. The spontaneous protest caught the world by surprise, before it was reprimanded by the Soviet regime. Images

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Vršovice neighborhood, Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Vršovice neighborhood, Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Wenceslas Square. A nod to French photographer of Czech origin Josef Koudelka, at the place where at the time he took a photo with the watch on his hand showing noon on the empty square, after the invasion of Soviet tanks (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Wenceslas Square. A nod to French photographer of Czech origin Josef Koudelka, at the place where at the time he took a photo with the watch on his hand showing noon on the empty square, after the invasion of Soviet tanks (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Commemorative plaque showing Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc, two students who set themselves on fire in protest against the normalisation regime imposed by the USSR (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Commemorative plaque showing Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc, two students who set themselves on fire in protest against the normalisation regime imposed by the USSR (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Prague, Ujezd, Malá Strana. Memorial to the victims of communism by Czech sculptor Olbram Zoubek and architects Jan Kerel and Zdenek Hoelzel, inaugurated on 22 May 2002 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Prague, Ujezd, Malá Strana. Memorial to the victims of communism by Czech sculptor Olbram Zoubek and architects Jan Kerel and Zdenek Hoelzel, inaugurated on 22 May 2002 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

The young Slovak Jana Neupauerova works for the Forum 2000 foundation founded by former Czech president Vaclav Havel. 'For me the end of communism means to open up to the world, but if we want to work on something we like we have to leave Slovakia for Prague' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

The young Slovak Jana Neupauerova works for the Forum 2000 foundation founded by former Czech president Vaclav Havel. 'For me the end of communism means to open up to the world, but if we want to work on something we like we have to leave Slovakia for Prague' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Vestiges of former factory chimneys in a residential neighborhood in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Vestiges of former factory chimneys in a residential neighborhood in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Petr Fleischmann, consultant to the ministry of foreign affairs, translates his last written article aloud. 'The visual changes of the city as well as the free circulation of people and ideas have had the biggest impact on me since the end of communism' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Petr Fleischmann, consultant to the ministry of foreign affairs, translates his last written article aloud. 'The visual changes of the city as well as the free circulation of people and ideas have had the biggest impact on me since the end of communism' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Kids playing in the street (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Kids playing in the street (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

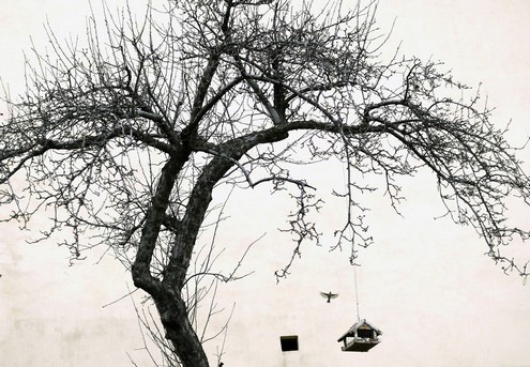

Springtime begins in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Springtime begins in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Michal and Petr in the popular neighborhood of Vršovice, where Petr Fleischman was brought up (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Michal and Petr in the popular neighborhood of Vršovice, where Petr Fleischman was brought up (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Petr Uhl, co-founder of Charter 77, created in opposition to the so-called period of normalisation, is still active in politics. 'The place of freedom where I lived all my life is very important to me.' After the division of the country, Uhl asked to have double nationality of Czech and Slovak, a case unforeseen by the law. He had to fight over five years to be able to have the double Czechoslovakian nationality, 'and only now I can celebrate' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Petr Uhl, co-founder of Charter 77, created in opposition to the so-called period of normalisation, is still active in politics. 'The place of freedom where I lived all my life is very important to me.' After the division of the country, Uhl asked to have double nationality of Czech and Slovak, a case unforeseen by the law. He had to fight over five years to be able to have the double Czechoslovakian nationality, 'and only now I can celebrate' (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Bus stop, Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Bus stop, Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Tramway in the streets of Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Tramway in the streets of Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

Czech Republic, Prague, March 2008 (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

A spring time in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

A spring time in Prague (Photo: ©Boris Svartzman)

It’s not been that long since the communist party took power in the Czech Republic, when its members thought they understood the needs of Czech society. A number of citizen dissidents, such as Vaclav Havel or Peter Uhl, and the men from the party, like Alexander Dubcek, helped mark the end of the sixties with the arrival of a new and free society. Socialism with a human face, rooted in the progressive indifference of the population until the systematic logic imposed by the USSR, seemed possible at last.

But above all the anniversary of the ‘Prague Spring’ reminds us of the support that Soviet repression received from the countries who had signed the Warsaw pact. A reality which froze all autonomy, of every abnormality for this power which didn’t doubt calling the period that followed as a period of ‘normalisation.’ More than repression, shouldn’t we be celebrating the immense battle for freedom, paralysed the day that the soviets intervened?

Petr Fleischman is a foreign affairs consultant in the Czech Republic. In 1968, he took part in the Paris barricades: ‘I had fun with my friends, but anytime I could get my hands on a radio, I would switch it on to find out how it was going in Prague. What happened there was symbolically much more important than May 1968,’ he recalls.

In the west, westernised countries protested for a concept of freedom which had been limited geographically by the communist bloc. For Petr Fleischman, Prague’s successes momentarily allowed ‘the left of democratic countries to dream that an economic and political regime, which eliminated the damages of capitalism with respect to human liberties, was possible.’ Now commemorating such an event in a world governed by economic liberalism is susceptible to forgetting the aspirations led to make a system which we don’t want to destroy more human.

So, did freedom come with the end of communism? If the country is built on a purification of its past and does not deny any opportunities of redemption of the idea of communism, doesn’t it delete the idea that that at one point, communism was a common aspiration? Like Fleischmann, we could think that ‘if the regime came down, the mental structures established in this time continued to exist in an equally dogmatic anti-communism.’ As if history forgot to figure out how to emerge in the following generations.

Thanks to Vítek Nejedlo

First published 29 April 2008 on cafebabel.com

Translated from Photos : 40 ans après le Printemps de Prague