Paper mills of discord along the Uruguay River

Published on

Translation by:

daniele calisti

daniele calisti

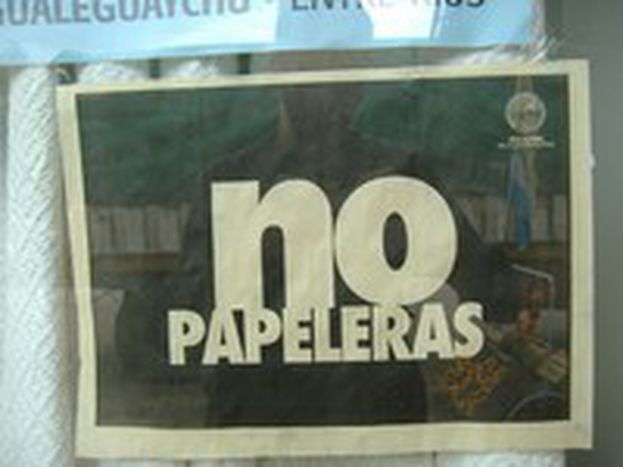

By building pulp mills, Finnish global corporation Botnia 'is willing to export pollution' along the binational stream, Argentina claims. Their announcements of further highway blockades is disrupting trade and travel

Sometimes natural barriers can poison international relations. The Uruguay River, which shares a mutual border between the homonymous little state overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, and the far bigger Argentina, is a good example. Especially when two big companies based in Europe (Finnish corporation Botnia and the Spanish Ence), are willing to work with Montevideo, and build up cellulose factories along the Uruguayan riverside of Fray Bentos.

Riverside row

Foreign investment, scores of jobs; should the project take off, the Montevidean government is already dreaming about all the new opportunities which will be created, with an estimated 2, 000 jobs coming from Botnia alone. But in Argentina, discontent has been accelerating on the same issue since 2005. They say their waterways will be polluted. The citizens of Gualeguaychù, an Argentine city on the river, organised massive roadblocks as a form of protest, and actively hindered the transit of goods and vehicles towards Uruguay.

Estela Vence, a 46-year-old Uruguayan citizen, has lived in Gualeguaychù for many years. She is supportive of the extreme measures. 'I have five children and three grandchildren, and I can barely see them during the roadblocks,' she told Argentine daily newspaper La Naciòn. 'But by opposing the cellulose factory, I am protecting their future.'

The quarrel has hit the big seas. Argentina has brought the case before the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Buenos Aires is accusing their neighbour specifically of violating a number of international provisions protecting international rivers. Argentine authorities claim that the production of cellulose is devastating for the ecosystem because of its environmental contaminants, such as furan and dioxin, which are difficult to biodegrade.

Meanwhile the Uruguayan government is ensuring that cellulose is bleached in a method avoiding using chlorine in gas form. New factories will thus use the so-called ‘ECF’ (elementary chlorine free) process. This environmentally friendly measure will be compulsory for EU member states from October 2007.

Mercosur at risk?

Despite Montevideo’s reassurance, new roadblocks have already been announced for the beginning of 2007. According to Uruguay’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Reinaldo Gargano, this is an 'attempt to finish Mercosur', the South American free trade agreement, which is inspired by the successful history of the European Union.

Recently Ence, a Spanish based company which had planned the construction of a paper mill a few kilometres from the Finnish one, abandoned its original project. They announced that the factory will be situated in the south instead, on the Río de la Plata, whose estuary (nicknamed the widest estuary in the world), opens onto the Atlantic Ocean.

But what is urging European companies to settle in Latin America to produce cellulose? Finnish journalist and biologist Janna Kanninen describes the appeal of the situations. 'In Latin America, the labour force is cheaper. There's a new capacity for eucalyptus markets, which will be ready to be used in ten years, whereas in northern Europe it takes from 60 to 120 years. Moreover, many developing countries have favourable tax regimes and a weak state control.’ There is also a concern to avoid domestic tragedies. In the summer of 2003, for instance, 7500 cubic metres of environmental contaminants flowed out of UPM/Kymmenem's pulp mill (one of Botnia shareholders), into Finland's largest lake, Saimaa.

Translated from Le cartiere della discordia sul Rio Uruguay