Older migrants of Europe: forgotten until when?

Published on

Translation by:

Monica BibersonThey came to work and in the end they stayed. Today the migrants of the 1960s are growing old in the cities of western Europe often in isolation and insecurity. Their discretion has turned them into an invisible generation. Portrait of retired immigrants whom everybody wants already buried

In France and Germany the pension reform is on everyone’s mind and is discussed at every corner but few voices concern themselves with the difficulties encountered by retired immigrants. After all, immigration is supposed to make up for the shortage in labour caused by the aging of the local population but not contribute. We seem almost to forget that migrants grow old too…

Discrimination from 7 to 77 years old

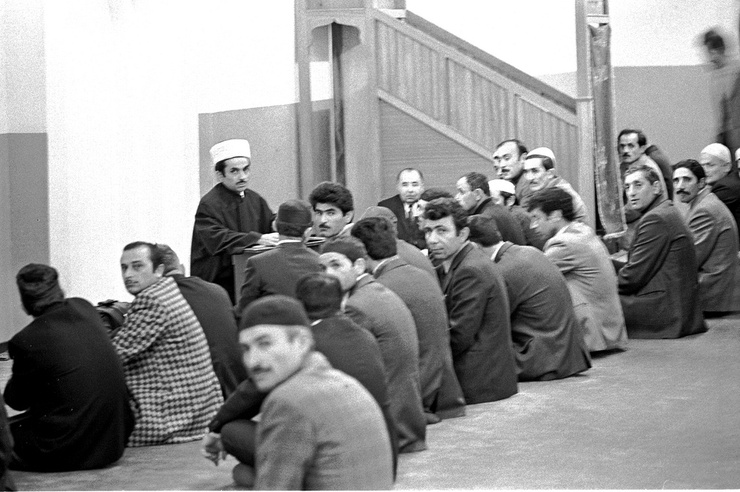

Yet the massive presence of older migrants concerns most countries of Western Europe, the so-called 'historical land of immigration', from France to Germany to the Netherlands to Belgium and the United Kingdom. Despite their growing number – with 500, 000 in Germany and 400, 000 in France – the older migrants aged over 60 remain invisible. In Germany they are called Gastarbeiter ('guest workers') and in France chibanis (Arabic for 'white hair'). The Gastarbeiter came to work in the fifties and sixties from Italy, Spain or the Maghreb and especially from Turkey, while the chibanis were 90% Maghrebi. While of different origins, their journey and the difficulties they have encountered over the years are identical and kept quiet.

Yet the massive presence of older migrants concerns most countries of Western Europe, the so-called 'historical land of immigration', from France to Germany to the Netherlands to Belgium and the United Kingdom. Despite their growing number – with 500, 000 in Germany and 400, 000 in France – the older migrants aged over 60 remain invisible. In Germany they are called Gastarbeiter ('guest workers') and in France chibanis (Arabic for 'white hair'). The Gastarbeiter came to work in the fifties and sixties from Italy, Spain or the Maghreb and especially from Turkey, while the chibanis were 90% Maghrebi. While of different origins, their journey and the difficulties they have encountered over the years are identical and kept quiet.

You do not have to live in France to hear the shouts of the strikers marching against the pension reform. The Polish, Lithuanians and Germans have all commented on the French demonstrations. Could it be that they have also sensed that the question of the 'older migrants' has been buried, as the co-ordinator of the French association of Maghrebi workers (l’Association des Travailleurs Maghrébins en France, ATMF) bemoans? 'Unions do not look at specific cases,' explains Ali El Baz. 'Certainly we talk more and more about women’s specific problems but never about those of the older migrants even though they find themselves in a similar situation.' Ali El Baz objects to the term 'chibani'because he does 'not like all these distinctions – chibanis, beurs – even if people use them sympathetically'. The situation of the older migrants is summed up by this 58-year-old worker in one word: 'Insecure. For one thing, they were hit the hardest by the wave of redundancies caused by the deindustrialisation of Europe in the 1980s. Then they had to go from one small job to another without always being able to pay their pension contributions.'

Disillusions and examples to follow

Who cares about this double disadvantage which today renders the old migrants vulnerable? On the one hand, as shown by the Enracinement (Settling) survey on ageing immigrants in France commissioned by the national pension fund (Caisse nationale d’allocation vieillese), they pay the price for doing what is often hard, backbreaking work: 28% of the chibanis are ill or disabled. On the other hand, because they have fallen prey to dishonest employers or not been able to hold a permanent job since the 1980s, they have worked longer but paid less toward their pension and therefore fewer of them have retired before the age of 65 like the other employees have.

'Even nurses sometimes refuse to attend their migrants’ homes'

Germany abounds with initiatives aiming to make up for the disadvantages its Gastarbeiter are subjected to. The concept of 'ethnic' care homes has been gradually developing. These care facilities receive aged immigrants and are adapted to their needs. The residents come from the same community (Turkish but also Arab or Russian) and can communicate in their native language which helps limit the feeling of exclusion. This system is absent in France where the chibanis tend toward 'self-censorship', as noticed by Ali El Baz in his own town of Clichy la Garenne where the activities offered to seniors do not bring together any of the numerous Maghrebis living in the city. Even nurses sometimes refuse to attend their migrants’ homes, as witnessed by someone who sees his retirement age recede into the future day by day. 'Ethnic' or not, it is desirable, indeed, essential that old migrants be given specific attention.

It's a bit like in Berlin – a city in which 25% of its inhabitants are the offspring of immigrants – where the catholic Sainte-Marie de Kreuzberg care centre and the Evangelical Waldkrankenhaus hospital reserve part of their establishments for old migrants. There are also other initiatives which see the light of day in Germany such as the dissemination of bilingual leaflets in English, French, Spanish and Turkish ('Sosyal Güvenlik') to inform foreigners about the German social security system. These are local initiatives which France does not lack either, for example, the social café (le café social) which welcomes old migrants in the mixed-race neighbourhood of the 18th arrondissement (one of twenty districts) in the north of Paris.

Europe? Don’t know it

While there is no shortage of local goodwill, a long-term 'glocal' vision is a different matter. When we ask Ali El Baz if he has heard of the project launched by the European council 'Elderly migrants – aging with dignity and continuing to play a part in society' ('Migrants âgés – vieillir dans la dignité et rester acteur de la société'), he answers that although he has been a member of the association for many years, he has never heard of it. 'If France does not communicate at the top, it is hard to guess.' It is a shame that communication has failed because this project, launched in 2009, offers guidance to member states in order to facilitate old migrants’ access to medical care, independence, integration and mobility, as well as encourage them to pass on their values, skills and experiences to young people in order to strengthen social cohesion. The talk has been talked – who will now walk?

Beside France and Germany, do you know of other concrete initiatives for keeping older migrants company in other European countries? Let us know!

Images: main (cc) gemeinde.niederhelfenschw il; Turks in Hamburg (cc) Heinrich Klaffs; on a break (cc)kikasso; bench chats (cc)Lucas Ninno/ all courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Les vieux migrants en Europe, une génération oubliée...Jusqu'à quand ?