Croatia: Refugees Reloaded

Published on

During the Balkan war of the 90s, thousands of Croat refugees were gathered along the Croatian-Serbian border. Today, the area is still a crucial hotspot for the EU migrant crisis: thousands of Syrian refugees, fleeing the turmoil in the Middle East, are passing through the Slavonski Brod camp. There, former Bosnian refugee Lorena Franjkić is helping them on their journey towards a new life.

Lorena Franjkić leans over a fence and dangles a plastic bag to the other side. A girl of four or five immediately pokes her head inside, working her way through the contents. As Lorena reaches lower to make the bag more easily accessible to the child, an inscription reading "welcome" becomes visible on her fluorescent orange vest.

The girl emerges from the bag. She looks at the ragdoll monkey she has fished out, then frowns, throws it back, and disappears inside the bag again. After a brief commotion, she emerges from the bag holding a doll, smiling. Lorena is smiling, too. She doesn’t ask questions, as if it were quite normal that in a white tent, at minus one degree Celsius, in a place that, only an hour before, the girl's parents didn’t even know existed, a small child is choosing a toy from a garbage bag.

The girl emerges from the bag. She looks at the ragdoll monkey she has fished out, then frowns, throws it back, and disappears inside the bag again. After a brief commotion, she emerges from the bag holding a doll, smiling. Lorena is smiling, too. She doesn’t ask questions, as if it were quite normal that in a white tent, at minus one degree Celsius, in a place that, only an hour before, the girl's parents didn’t even know existed, a small child is choosing a toy from a garbage bag.

"Hani," the girl says, happily pointing to the doll in pink clothes. Other children approach, dig into the bag, take out teddy bears, plastic crocodiles, or velvet monkeys. The girl reappears with another doll. "Who’s that?" Sandra asks in Arabic. Sandra’s father is Syrian, her mother Croatian. She has been helping refugees ever since she fled Aleppo for Croatia. "Hani’s mama," the girl answers, while her mother warns her that she should choose between Hani and her mother since they cannot continue on their way with two dolls. "I’ll take care of them!" the girl exclaims and hugs the dolls firmly.

The girl is one of the 850 refugees who arrived by train on the afternoon of the 25th of January 2016 at the refugee transit camp in Slavonski Brod, a small town on the Croatian border to Bosnia and Herzegovina. It's the border between the EU and the other European countries. The refugees travel from Serbia by train and stop in Slavonski Brod, where they are registered by the police before continuing on their way by train, first to Slovenia and then further, deeper into Europe.

Slavonski Brod is only a brief stop on their journey. The Croatian Ministry of the Interior – in charge of the camp – doesn’t give them much time to rest from their long and weary journey. However, the refugees say that it is the best organised camp on the Balkan route. Lorena is distributing clothes from an assorted heap. A young man asks her for warm shoes. Men's shoes are highly coveted, so there is a shortage. Lorena must lean over the fence in order to estimate whether he really needs a new pair.

It doesn't feel right when she is forced to judge other people's needs like this, but she has no choice – someone might appear who really needs those shoes, and she won’t have any left. Her job sometimes consists of hard decisions, as she cannot help all those in need. But satisfaction prevails. There are the smiling faces of children, refugees raising their thumbs as they shout "Really great!" and messages from those who have finally reached their destinations. Lorena is a volunteer helping those refugees for whom Croatia has become a stop on their way along the Balkan route.

It doesn't feel right when she is forced to judge other people's needs like this, but she has no choice – someone might appear who really needs those shoes, and she won’t have any left. Her job sometimes consists of hard decisions, as she cannot help all those in need. But satisfaction prevails. There are the smiling faces of children, refugees raising their thumbs as they shout "Really great!" and messages from those who have finally reached their destinations. Lorena is a volunteer helping those refugees for whom Croatia has become a stop on their way along the Balkan route.

As she watches the children, Lorena cannot help but remember herself when she was not only their age, but also in their situation. She remembers the tanks and the uniforms of the UN Peace Corps, and the moment that she left the occupied town where she had lived in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was in 1994, when she was barely four years old. She left with her mother for Germany on a refugee bus. Her father stayed and fought in the war. She remembers the toys she received, especially a monkey that she took with her wherever she went, and a white clown, which still sits on her work desk. "The only thing my parents ever say about the war is: 'May it never happen again.' It's only now, when I see these people, that I realise how difficult it must have been for them, and that's probably why they never talk about it," says Lorena. In 1997, they returned from Germany and settled down in Croatia, in a small Dalmatian town.

In the early 1990s, Croatia received around 650,000 refugees, mostly from the occupied Croatian territories, but also from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Around the same time, some 150,000 people fled Croatia. Two and a half decades later, Croatia faces another wave of refugees. "Had I been older during the war, I would have been a peace activist. When this humanitarian crisis started, I knew that I had to help, since human lives are at stake again. I felt that this time I could do something."

When Hungary closed its border with Serbia in September 2015, refugees from the Middle East were left with a single option – to cross Croatia on their way to Western Europe. Thus, in mid-September, thousands of people started entering Croatia across the fields in villages along the Serbian border, where the population had similar memories of the war in former Yugoslavia, since Serbian forces had occupied this area.

Again we can see hundreds of exhausted and hopeless people walking with plastic bags in their hands. In villages along the border, the former refugees came out to meet the present ones, bringing them water bottles and their children's clothes, while women offered them sweets and volunteers created hotspots where refugees could charge their cell phones. "When we had to leave our homes, we also needed other people's help. That’s why we feel for these people who are currently fleeing," says a woman from Tovarnik, the closest village to the border.

605,000 refugees have entered Croatia in the time from when the migrant crisis began to when Lorena went to aid refugees in Slavonski Brod. Since then, almost all of them have already left. Croatia is not a country in which they would willingly choose to stay. Slavonski Brod is now the only place in Croatia with an influx of refugees. "Everyone wants to go to Germany. It’s just like that joke, where a Croat asks a Bosnian what he would do if the world were about to end, and the Bosnian answers: 'I would take my wife and kids and off to Germany we would go!'" says a volunteer in Slavonski Brod.

Croatia is not a country where young people like Lorena would choose to stay either. With its high youth unemployment rate – Croatia being among the EU countries with the highest unemployment rates (third just after Spain and Greece) – as many as 85% of young people have considered moving abroad. The generations that grew up in a society marred by the traumas of war and stunted by meagre economic growth are now stuck in a prolonged economic crisis of increasing social inequalities. As for Lorena's friends, many are studying abroad, just like she is – she travelled down to Slavonski Brod from Brno, in the Czech Republic, where she is enrolled in a joint sociology programme. She plans to continue her studies abroad, but she would like to return to Croatia afterwards. "I have spent a semester in Finland and it's easy to live a carefree life in such an orderly country, but I feel responsible for contributing to my own community. Croatia is my field of struggle," she says.

Croatia is not a country where young people like Lorena would choose to stay either. With its high youth unemployment rate – Croatia being among the EU countries with the highest unemployment rates (third just after Spain and Greece) – as many as 85% of young people have considered moving abroad. The generations that grew up in a society marred by the traumas of war and stunted by meagre economic growth are now stuck in a prolonged economic crisis of increasing social inequalities. As for Lorena's friends, many are studying abroad, just like she is – she travelled down to Slavonski Brod from Brno, in the Czech Republic, where she is enrolled in a joint sociology programme. She plans to continue her studies abroad, but she would like to return to Croatia afterwards. "I have spent a semester in Finland and it's easy to live a carefree life in such an orderly country, but I feel responsible for contributing to my own community. Croatia is my field of struggle," she says.

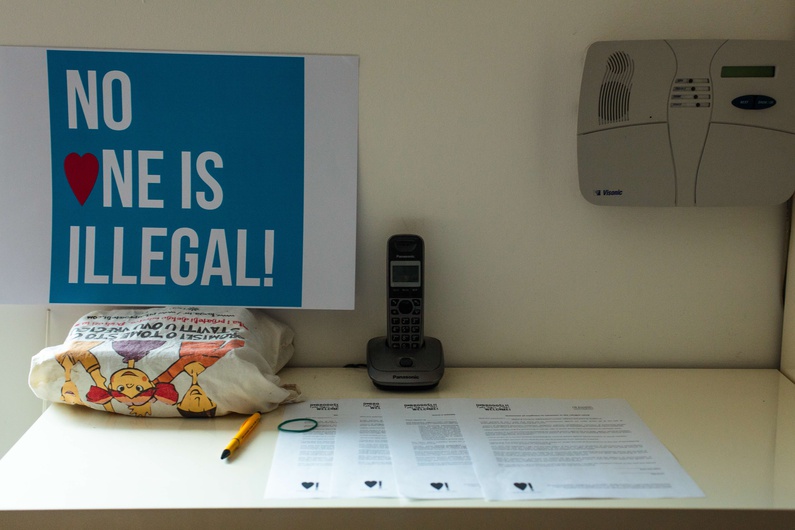

We drive back to Zagreb. Lorena's five-day volunteering shift has ended. We are listening to the news. The new, right wing government has taken the place of the previous, left-of-centre government in Croatia. Lorena fears that closing the borders for refugees will be among the new government's first decisions. She is afraid of nationalism and xenophobia gaining ground. The election campaign of the new government played a card that widened the ideological gap in society. "Young people my age are more traditional and closed-minded than the generations before the war. They have grown up in an ethnically and religiously homogeneous Croatia, where they haven’t gotten used to people being different than them," says Lorena. She still has hundreds of kilometres ahead of her before she reaches Brno, where the little clown is waiting for her that has comforted her over the past 20 years since she was a refugee in Germany. Soon she will return to Slavonski Brod to "welcome" once more new refugees arriving in Europe.

---

---

Text: Barbara Matejčić

Photography: Matic Zorman

---

---