Why right-wing extremism continues in east Germany

Published on

Translation by:

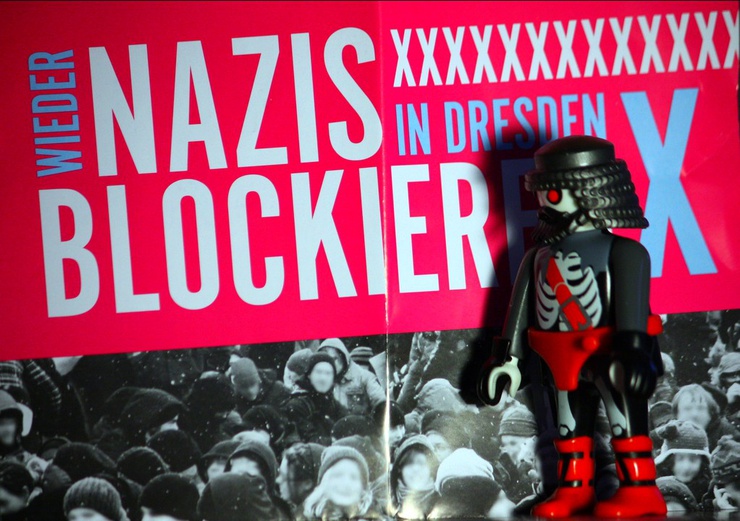

Sebastian BaciuNovember 2011 saw seven people arrested in connection with a right-wing terror cell based in Zwickau in east Germany. The cell was allegedly responsible for ten murders over thirteen years. Since Germany’s reunification in 1991, the formation of extensive ‘no-go’ areas in parts of the former GDR hasn’t gone unnoticed but has remained tolerated

It would be untrue to call Germany the most racist country in Europe. Statistically, right-wing extremist ideas are less widespread here than in France, for example. Nonetheless, the true problem here, namely the violent young men who believe in right-wing extremist ideology and live predominantly in eastern Germany, is often played down. Why did it take the serial murder of several Turkishsmall business owners and one Greek in November 2011 for us to finally realise this?

Murderous racism in Germany

For more than twenty years, the public has reacted with terrifying apathy to this type of murderous racism. Official figures that attempt to tally the violence often play down the facts. According to the Amadeu Antonio foundation, there have been over 150 victims of right-wing extremist violence since Germany’s reunification. However the official statistics of the interior ministry only record between forty and fifty such cases. In the case of the so-called ‘Doner murders’ (a reference to the fact that many of the victims of the Zwickauer cell owned or operated kebab or fast food stalls), investigators spent more than a decade looking for a suspect amongst Turkish criminal groups. They never investigated the theory that these crimes might have been racially motivated. Even the informal name given to this series of murders demonstrates a characteristic lack of empathy.

In eastern Germany, many tend to avert their eyes when confronted with xenophobia. Some writers have attempted to explain the situation. Frey Klier terms it the ‘brown legacy’ of the GDR in reference to the trademark colour of Germany’s national democratic party (NPD), the inheritors of the national socialists. In a different article, author Peter Schneider presents his opinion that the Zwickauer terror cell developed as a result of the GDR’s racist ideology. However, these former comrades tend to conclude their thoughts by waving aside such concerns. ‘Yet these are our children!’ they will say, or ‘They’re dumbasses. They are all far too stupid to think politically.’ This sort of explanation sweeps the problem under the carpet.

No true generational conflict

One often hears the tired mantra that ‘all authority has collapsed since reunification.’ Yet no matter how often this is repeated, it’s far from true. If it were, then ‘our children' would have finally come to terms with their parents’ past during the GDR era and would have long since asked them the necessary questions. Yet there has never been a true generational conflict. Instead, many feel solidarity toward a parental generation which seems to have lost everything– a sentiment perfectly in keeping with the spirit of the closed society inherited from the GDR. In this context, it is important to address the attitude of parents and grandparents as well as that of teachers and those in education. Those who believe that zero hour started with the reunification have learned nothing from history. Even people born after 1989 or who were in school at the time might have been exposed to the authoritarian and xenophobic thought typical of the GDR regime.

‘Unemployment is to blame.’ This fairy tale has held sway even though studies show that unemployment alone doesn’t lead to the formation of a right-wing extremist disposition. Victims of right-wing violence are often the homeless and others whose lives are considered to be ‘worthless’. Many neo-nazis are equipped to the highest technical standard and rarely lag behind the police in terms of their gear. Moreover, the right-wing political scene hardly suffers from a shortage of financiers. The amount of money that has flowed from the federal office for the protection of the constitution to police informants in right-wing circles has stunned the public.

Will against prejudice

Let us be frank. This is not only about poor sods, dumbasses, and the disenfranchised. There are plenty of dignified gentlemen wearing pinstripe suits who use their fortunes to train their ‘boys’. Often, they are helped by parties inside and outside the NPD who do their best to maintain a spotless facade. The Zwickauer bomb-makers, who narrowly escaped the police in 1998, point to an additional problem: regionalism. Officials and police officers have often gone to school with right-wing extremists and might therefore not be entirely unsympathetic to their cause. Small gangs and other decentralised groups prone to violence terrorise entire areas. They are difficult to prohibit and cannot be repressed unless society as a whole takes it upon itself to do so. Meanwhile, the neo-nazi scene in former west Germany has also enjoyed renewed growth since reunification. In addition, it has become more radical and militaristic.

What followed was short-lived disgust, a few sham-debates and ersatz-solutions such as banning the NPD party as well a call for an ‘insurgency of the respectable’. Long term solutions were not on offer. ‘No-go’ areas, gangs and underground neo-nazi radicals – they continue to persist unchallenged. The continued media hype just amplifies the problem. If public discontent is seen solely as a populist ‘fig leaf’, it will likely serve only to exacerbate the situation. It is certainly a good thing that the residents of Zwickau held a silent vigil for the victims of right-wing violence. Nonetheless, the network of ‘brown’ thought that has enveloped the region has still not been shattered. That can only be accomplished by the collective will of courageous citizens and society as a whole. However, prejudice is already rife amongst young people. According to a poll conducted by the criminological research institute of lower Saxony, 40% of German youth wouldn’t like to live next to a Turkish neighbour. This must change. Yet to change anything, both the people and the government must want it.

The author, Inka Bach, is a member of the Berlin-based artist’s initiative 'courage in the face of xenophobia' (Courage gegen Fremdenhass e.V.), founded by Peter Schneider in 1991. Her works include a political diary bearing the title ‘We don’t know the foreigners’ about right-wing extremism and the radio drama ‘Whoever counts the victims also calls their names’, about people who died as a result of rightist violence since Germany’s reunification

Images: main (cc) litteronly; fish (cc) xrrr; flyer (cc) rpenalozan/ all courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Rechtsextremismus in Deutschland: Auch wir sind schuldig