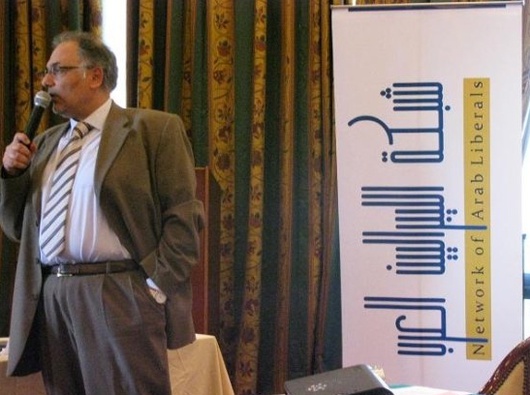

Wael Nawara: 'Secular is a word we Egyptians used to use wrongly'

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah GrayA nocturnal meeting with the second-in-command of the El Ghad ('The Tomorrow') party, Egypt’s main force of liberal opposition to Mubarak’s regime

Call it good conscience. But when I travel to spectacular countries living under illiberal regimes, I cannot avoid causing a bit of chaos for myself. Egypt is no exception when, on a warm Cairo night in late April, I meet Wael Nawara, second-in-command of the Tomorrow party, Egypt’s main force of liberal opposition to Hosni Mubarak’s regime.

Into politics alongside Ayman Noor

We land at Cairo Airport at ten in the evening. The appointment with the dissident Nawara is set for 11pm. The whole interview is a nocturnal affair, and our return flight is booked for the early hours. The schedule is endangered however when our taxi is soon swallowed up by the mad Cairo traffic. Through the din of tooting horns and lights, the driver bashes the car around like a punch ball. At eleven thirty we arrive in an important residential area of Cairo. Nawara opens the door to his apartment. At 49, the former marketing expert and politician in his spare time is now deputy to Ayman Noor, who came second in the 2005 presidential elections. After a globetrotting career in the oil industry, Nawara got the call to return to his homeland and try to change things. 'In 2002 I started thinking about creating a political party. I was convinced of the need for economic reform in order to relaunch my country. But I realised that there are some problems which the economy cannot solve. Political reform is needed.'

We land at Cairo Airport at ten in the evening. The appointment with the dissident Nawara is set for 11pm. The whole interview is a nocturnal affair, and our return flight is booked for the early hours. The schedule is endangered however when our taxi is soon swallowed up by the mad Cairo traffic. Through the din of tooting horns and lights, the driver bashes the car around like a punch ball. At eleven thirty we arrive in an important residential area of Cairo. Nawara opens the door to his apartment. At 49, the former marketing expert and politician in his spare time is now deputy to Ayman Noor, who came second in the 2005 presidential elections. After a globetrotting career in the oil industry, Nawara got the call to return to his homeland and try to change things. 'In 2002 I started thinking about creating a political party. I was convinced of the need for economic reform in order to relaunch my country. But I realised that there are some problems which the economy cannot solve. Political reform is needed.'

Then in 2003 he met Noor and the El Ghad party was founded. 'It was me who directed Ayman’s presidential campaign,' Nawara tells me. The slogan? 'Hope for Change. Obama copied us.' He’s joking (but not that much). Nawara lists the party’s policies: 'Bridging the digital divide, tax relief for small companies, political reform... We had a state contribution of less than one hundred thousand euros (£857). We won 540, 000 votes according to official estimates and 1.7 million according to our own information. After the elections Ayman Noor was arrested by the regime. I went to visit him regularly and I have to say that he did not suffer any maltreatment. Then came the 6 April youth movement; at least twenty five of our members were arrested. Today there are still one hundred or so in prison for political reasons.' In November 2008, 'criminals hired by the regime' burned down the party headquarters.

Parallel state theory

'Egypt is a rich country but it has been robbed by the corruption of Mubarak’s national democratic party, which is now much hated by the people.' In addition to corruption, there are the problems arising from Islamic fundamentalism. 'My mother didn’t wear the veil. In her day less than one third of women did. Today 80% do, although I have to say that over the past few years the trend has been reversed. 9/11 and the 1997 Luxor attacks scared the Egyptians, who are a peaceful people.' For Nawara, Egypt does not need to be 'secular, a word we used to use, wrongly,' but instead needs a healthy separation between the state and islam, but with respect for the religion, since it is engraved in the culture of the country.

'My mother didn’t wear the veil. In her day less than one third of women did'

But which is the country’s biggest problem: Mubarak or the muslim brotherhood, Egypt’s main radical Islamic organisation? 'They are two sides of the same coin,' replied an amused Nawara. 'They’re like Tom and Jerry. The fear of one legitimises the existence of the other.' So when will change come? 'In the next three years. Mubarak’s party has been made weaker by its corruption. But there will not be a big revolution. It will be more like a broad consultation which will legitimise the opposition. In Egypt the situation is what is called a parallel state. For example, the public education system is poor, so many Egyptians send their children to private schools in the afternoons. The official press isn’t free. That’s why there are so many blogs, why Facebook is so popular. But that’s why we need a new president. Mubarak cannot seriously expect to transfer power to his son, as though it were a hereditary monarchy.' But to encourage change there must be international support. Who is the main ally for Egypt’s liberals? The USA or Europe? 'Neither. Our main ally is the Egyptian people,' Nawara replies with aplomb. 'International support is certainly important in a globalised world but, for example, we do not receive any funding from abroad. What we are trying to explain to the United States is that if we do not restore faith in liberal values, the Middle East will fall into the hands of the fundamentalists, from Morocco to Pakistan.'

My time is up, the plane awaits me. Nawara takes me to the airport in his beautiful car, gliding through the now deserted streets. We arrive at 1am. Or so I think. At security I am told that, at exactly one o’clock, Egypt has switched to summertime, putting the clocks forward by one hour. 'Sir, you have missed the flight.' At least I have a clear conscience.

With thanks to France Dutertre

Translated from Io, dissidente d’Egitto, Mubarak e Tom & Jerry