Ukrainian democracy speaks Turkish in the Crimea

Published on

Translation by:

sharon rapose

sharon rapose

The Ukrainian Tatars, a minority deported by Stalin all those years ago, still suffer from discrimination. Their support for Yushchenko, leader of the ‘Orange Revolution’, has now turned to fear

Following the presidential elections on December 26th, in Kiev the revellers are still partying after the victory of Yushchenko and the departure of the first international election observers. Elsewhere in Ukraine the situation has been, and still is, far more tense. In Simferopol, the capital of the autonomous republic of Crimea, Yushchenko’s supporters speak not Ukraninan but Turkish and do not even amount to 20% of the local population.

Following the presidential elections on December 26th, in Kiev the revellers are still partying after the victory of Yushchenko and the departure of the first international election observers. Elsewhere in Ukraine the situation has been, and still is, far more tense. In Simferopol, the capital of the autonomous republic of Crimea, Yushchenko’s supporters speak not Ukraninan but Turkish and do not even amount to 20% of the local population.

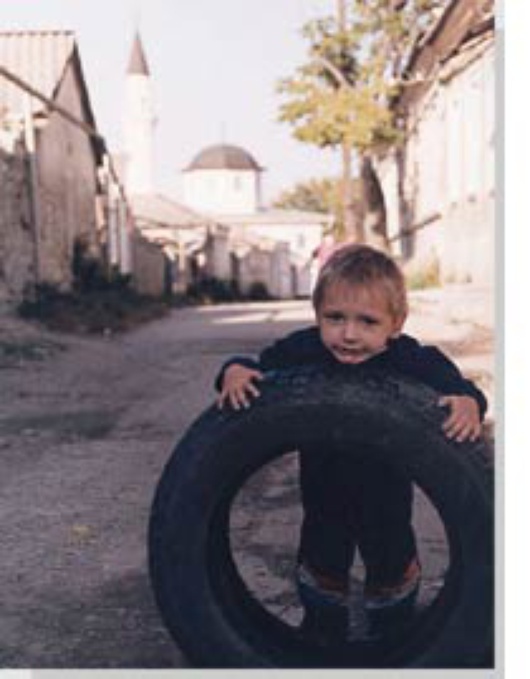

These supporters are the descendants of the Tatars that Stalin deported from the Crimea on a single day in 1944 to the central Asian republics, primarily Uzbekistan. 46% of the deportees perished during the course of this ‘relocation’. In order to grasp the severity of their treatment one just has to look at Lavrenty Beria’s actions. An executioner by profession, who gained experience in the art of genocide during the 1930s, Beria packed all the Tatars attempting to evade capture onto a boat to be sunk in the deepest waters of the Azov Sea. Later, Nikita Khrushchev did not allow the Tatars to return to the Crimea to re-establish an autonomous republic. The Tatar diaspora, again scattered in the steppes as in the times of the Khan Dynasty had to wait until the collapse of communism to recover its quite literal ‘lost ground’ in the Crimea. In their Crimean homeland, the Tatars now make up less than 300,000 of the 2 million inhabitants.

Communism has ended but Russian control remains

Today in Crimean cities such as Simferopol, Sebastopol, and Yalta, 80% of the population is Russian-speaking and the mood is far more Russian than Ukrainian. In the central square of Simferopol, the only accompaniments to the Tatars’ orange pro- Yushchenko flags are a statue of Lenin and the three colours of mother Russia; there is not a trace of the Ukrainian flag. And any time they are required, the Russians appear everywhere. Apart from the Black Sea naval base of Sebastopol, Russian military forces have another ten extraterritorial posts at their disposal, inland. As a result, in the Crimea there is no threshold that cannot be crossed, and no action that cannot be computed by the Kremlin’s intelligence and special services. Since 1991, the Tatars, free of secessionist pretensions, have fought in vain to defend their Turcophone identity and protect their moderate Sufi Islam tradition from infiltration by the more puritanical Wahabi Islam, which Moscow and Kiev have often manipulated and, cynically, encouraged. The Tatars, who have criticised the previous Ukrainian president, Kuchma, of not protecting minority groups, have now brought their case to international attention by becoming members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO).

Another Gorbachev: a Tatar nightmare

As the leader of the ‘Orange Revolution’ and the next president of the fledgling Ukrainian democracy, Yushchenko was the inevitable choice for the Tatars. After the elections of December 26th, Nadir Bekir, a member of the self-declared Tatar parliament since 1991, now fears that the ‘orange hero’ may turn out to be another Gorbachev. “Now that the West considers Yushchenko to be the champion of Ukrainian reform”, muses Bekir, “who will listen should he carry on the same policy of discrimination towards the Tatars?”. And all fear the perfect excuse from the so-called international community: “At least it’s Yushchenko that you have now!”

In addition, the risk exists that post-electoral agreements between the previous and current leaders of Ukraine may compromise the potential for change, despite the Ukrainian “revolution”. After the 12,000 international observers have all returned home, it would be advisable not to stop watching Ukraine, and instead consider cases such as that of the Crimean Tatars as a litmus test for the reforms promised by the new direction. In this way, we might be able to avoid Yushchenko turning into a Gorbachev or a Yeltsin, whereby, beyond appearances, Ukraine would not change at all.

Translated from La democrazia ucraina parla turco a Yalta