Three Cheers for the EU!

Published on

Translation by:

dominic harrison

dominic harrison

Sport proves it: the majority of people still identify themselves along national lines. However, beneath the surface, all is not as it seems.

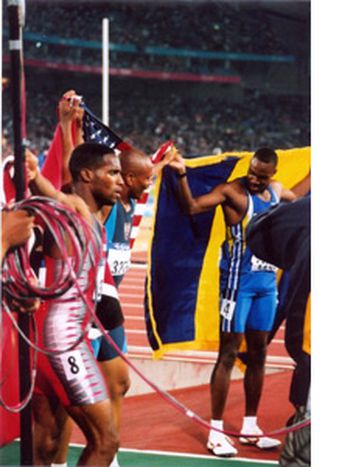

The opening ceremony of the twentieth Winter Olympic Games is a matter of days away: 2,500 participants will march into the stadium in Turin, behind the flags of their 85 respective nations. From the 10 to 26 February, sports fans all over the world will nervously watch ‘their’ athletes- cheering them on, and perhaps even shedding a tear with their fellow nationals when they take to the winners podium to the backdrop of their national anthem. This spectacle would not be half as interesting if one didn’t identify at least a little with those taking part. The bond felt between fan and participant is not based on sympathy or aesthetics, but simply along nationalistic lines. This feels natural to us, but does it really exist?

Farmers, town citizens or aristocrats

Two hundred years ago this just was not the case. This is not to say that there was no group identification back then; identification was merely a lot more flexible. One could simultaneously belong to a number of groups: farmers or aristocrats, Catholics or Protestants, inhabitants of one village or another. In short, self-identification was very much dependent upon social standing. It was not until the end of the 18th Century and the ideals of the French Revolution that the concept of the nation became commonplace – a community of interest, built upon the framework of civic-political values. Identification with the civic-territorial nation would cede attachments to any other group, acting as an umbrella, under which the nation’s disparate elements would unite. The success of this rationale later led to the relationship being turned on its head: the nation became not a community of interest of the nation’s citizens, but an extension of ethnic elements, around which political order was built. Herein lies the root cause of much of today’s global geographical and political conflicts.

Brotherly duel in the World Cup

Now, back to sport. The Olympic Games reveal that dividing the world into nations, in accordance with this principle, is not ‘natural’. In an ice hockey tournament, two teams face each other, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. But, the players of these teams would have cheered on the same team, the Czecholsovakian team side by side as children. The Croatian alpine skier, Janica Kostelic, was born as a Yugoslavian. Similarly, sixteen years ago, different members of the German team, now united in the race for medals, would have cheered on rival contenders for gold.

Looking at the case of immigrants competing in sporting events, it is also not clear which nation the athlete naturally identifies himself with. Recently a storm raged in the German football world, when both the German and Turkish Football Associations raced to claim Nuri Sahin, who grew up in Germany, as one of their own. Both countries wanted the son of Turkish parents to pledge allegiance to their nation. In the end, Turkey won the dispute, as had often happened in previous cases. At the same time, Lukas Podolski, Miroslav Klose und Lukas Sinkiewicz play for the German national team, yet could all have appeared in the Polish national side. In the upcoming 2006 World Cup this summer, a ‘brotherly duel’ is on the cards: Salomon Kalou will play for his newly adopted nation, the Netherlands. Interestingly, first round matches will see Salomon face his brother Bonaventure Kalou, who is representing the Ivory Coast.

Thuringia, a successful ‘nation’

So why does the logic of nationalism work anyway? Why does a Sicilian cheer when a skier from the Lombardy region takes first place in the downhill tournament? And why do Tyroleans get angry at the same sight even though Lomardy is geographically much closer to Austria than Sicily? One could mention numerous other divisions here. During the last Olympics in 2002, the German media constructed a version of the medals table, which showed the German federal state of Thuringia as being the third most successful ‘nation’. So why doesn’t an Alsace, Silesian or even Catalan ‘national’ team exist? Or perhaps even a team, which represents the European Union? An overarching language is not reason enough. Germany and Austria, America and the United Kingdom all exist as separate nations despite sharing mother tongues. Similarly, nations exist in which a number of languages are used, such as Switzerland, Belgium or Canada.

Identification with a nation is strongly reinforced in schools and particularly in history lessons. But the media plays an equally influential role. In the beginning, books and newspapers brought this about; nowadays, television fulfills the same role of creating a sense of togetherness – especially when relaying news of sports events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup.

But perhaps a European identification will develop in upcoming decades. Imagine a future of Frenchmen cheering on English, Finnish and Hungarian sportsmen because ‘their’ athletes belong to a greater whole. We will no longer talk of Americans or Brazilians winning medals, but EU citizens.

Translated from Jubeln für die EU