"This is not a shopfront, it is a confiscated property, a community resource" (2/3)

Published on

Translation by:

Tom Metcalfe

Tom Metcalfe

"New Landlords: when Italian civil society moves in with the mafia" is the latest series from Cafébabel on citizens who are reinvesting goods confiscated from organised crime by the courts. How and why have projects been created for the common good in places which, in the past, have served the interests of the mafia? In the second part of this investigation, we explore the city of Genoa.

The wind swirls around the pedestrianised streets of Genoa's historic centre. You can hardly see the sky amongst the towering buildings. In this concrete labyrinth, you can find everything you need in the small shops squeezed in next to each other. Although there are fewer sailors and tourists here than before, the COVID-19 pandemic has not managed to strip the the area of its typical port city liveliness.

By 9am, the prostitutes and drug dealers already occupy their corner of the street. Across from them, grandfathers and grandmothers pick their vegetables at the greengrocer's and young people hurriedly drink an espresso at the counter of the café before heading off to work.

However, a number of shop roller shutters remain down. Trade has suffered from the health crisis, but that is not the only reason. Some of these shops are also confiscated property of organised crime. And few people here know that yet. Firstly, because there is still a popular belief that the mafia in Italy is a "southern thing". And secondly, the belief that a typical mafioso owns Ferraris and luxurious villas, rather than dirty, run-down shops.

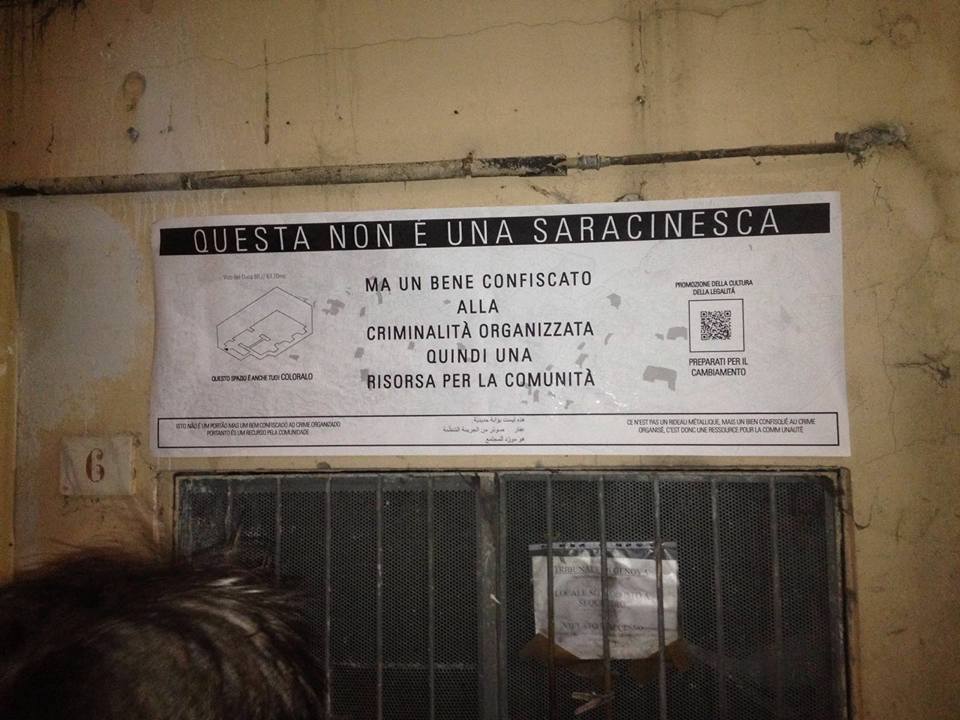

In 2016, following the conviction of the mafia family, the Canfarottas, and the subsequent confiscation of their properties by the courts, a group of scouts supported by activists from Libera - a coalition of 1600 anti-mafia associations born in 1995, as we saw in the first episode of this series - launched a public awareness campaign: the "Chantier de la légalité responsable" (Responsible Legality Campaign) (http://mafieinliguria.it/confisca-canfarotta/).

Their aim is to inform passers-by about the importance of salvaging these properties: “This is not a shopfront, but a confiscated property from organised crime which is now a community resource”, is the message that is beginning to adorn the shop shutters and doors of these former crime hotspots.

29 year-old David Ghio was a part of this great movement at the time. The student and Libera activist recalls: “At the start, we thought about occupying these places, but it was very complicated. We had to do something, since the town hall wasn’t doing anything”. Afterwards, the scouts painted 14 shopfronts with poetic and colourful messages. ”That had a national impact. The issue was even raised at a parliamentary session in Rome.” At that time, the “Canfarotta confiscation” was the largest single seizure of property in Northern Italy.

Local groups of residents and business owners have also organised events over several months and began to lend their support to the initiative in order to prompt the authorities to make an inventory of the available buildings and premises and to launch calls for subsequent projects. Finally, things got moving and the City obtained the management of the first nine properties in February 2017.

Having heard about what was being done elsewhere, the mobilisation of the Genoese was fuelled by the conviction that the social use of confiscated properties was a factor with innumerable benefits, not only from a socio-economic or political point of view, but also from a philosophical and educational standpoint. Throughout Italy, there are thousands of examples.

A whole host of benefits

Italian legislation is going much further than what is being done elsewhere. "Generally, court sentences stay within the parameters of the penal institution and the everyday citizen doesn't notice anything", explains Federico Cafiero de Raho , national Anti-Mafia and Counter-Terrorism Public Prosecutor.

"However, if a citizen realises that a mafia house has been confiscated and that it is being used to address social issues or other projects which can't always be achieved by public institutions, the population learns an important lesson from this", adds the examining magistrate, who has also condemned members of the Camorra mafia."They are living proof of state action".

The free provision of premises facilitates the emergence of social projects which, without them, could not be possible due to a lack of resources. This makes it possible to implement more social policies in specific areas, particularly for vulnerable groups (care centres for people with disabilities, social housing, reception centres for minors or women victims of violence, etc. According to Libera's calculation assets of properties not managed by the local authorities, close to half of projects (55%) fall into this category, - followed by cultural promotion, which is that of sustainable tourism (27%), and then agricultural projects (11%).

This also facilitates the development of heritage, since we avoid deteriorating buildings or unoccupied sites and which could negatively affect the quality of life in the neighbourhood.

Since its inception, the social use of confiscated properties (USBC) has been invested in by social and solidarity economy actors, thanks to their compatible DNA. A large number of agricultural cooperatives also hold confiscated land. These businesses believe in jobs and make use of a new economic deal. This is the case in the "Al di là dei sogni" cooperative in Campania, which employs, amongst others, people with psychiatric care, African migrants, and former prisoners.

Often, the reused confiscated property provides training opportunities for young professionals. "It's a central component for us: you have to create a desirable model, get them to understand it and prove that a social economy is a solution which offers a notable qualitative improvement and real job opportunities", explains Mauro Baldascino, expert and activist.

In his view, it is a way to propose an alternative to the "mafia" economy, but also to galvanise the region with an alternative to direct state aid.

"It is about modifying the relationship with work, and moving from an assisted economy to a more independent economy. Moreover, this more collaborative approach is a new thing in our regions, which have long been characterised by individualism in the past".

In a way, it is the local community that has an opportunity to take charge of itself, to analyse its own needs, and then to set up a project based on them and carry it out itself. The whole history of the anti-mafia movement is linked to the question of citizen emancipation.

"All the work being done by the anti-mafia associations is to rally citizens together so that everyone is conscious of the mafia problem and feels capable of standing up to it in their day-to-day lives.", explains sociologist Elisabetta Bucolo.

The USBC facilitates regaining possession of economic control and local life, in a collective effort which must avoid hero worship, which refers to "a circle of courageous people, which exonerates everyday citizens of any responsibility", she outlines. This makes it possible to convince those who fear the mafia, or who think that nothing can be done against the mafia powers.

_“We can be scared, we can say to ourselves that we can be subjected to violence by people who come back with guns and can kill us”, testifies 35-year old Carmela Papa, administrative officer for the farming cooperative Al di là dei sogni, a 100 hectare property north of Naples which, at its inception, was subject to threats from the Moccia clan who formerly owned the land.

“Some are scared to work here, but the reality is that that is not the case. I prefer to speak to people about the interesting and beautiful things that we do here”, she adds.

Most of the time, the projects which flourish the most from confiscated property are the ones which provide new opportunities for citizens to get involved and enrich their community with activities that maybe didn’t exist beforehand and which allow residents to find a safe space through creating new links between associations.

This is exactly what happened in Quarto Piano. On the 4th floor of 42 de la via Landinelli in Sarzana, a coastal town in Liguria on the Tuscan border. Around a big table, the town’s young people come to do their homework, participate in film club sessions, take cooking courses, etc.

The 3 bedroom apartment has been confiscated from a local businessman accused of having worked with the mafia. The place is self-managed by the associations that use it and this is an argument that the defenders of the USBC use to show its strong political significance, in the sense that it offers practical opportunities to really experiment with the notion of "common good".

In a confiscated former shop in the centre of Genoa, an association for new foreign arrivals has set up a classroom, overlooking the street, to teach Italian.

There’s no better message to send than an open shop front”, outlines Michaela Tirone, president of the Pas à Pas association. “There are already mini-markets everywhere here, so it is better to put a social place there and help the neighbourhood come together in a positive way”_.

Confiscated properties often serve as educational and commemorative places. They bear the names of the innocent victims taken by the mafia. Don Peppe Diana, Giancarlo Siani, or even Francesco Aversano, a young boy killed by Camorra in September 1973 and whose name was given to a park in the commune of Casal di Principe.

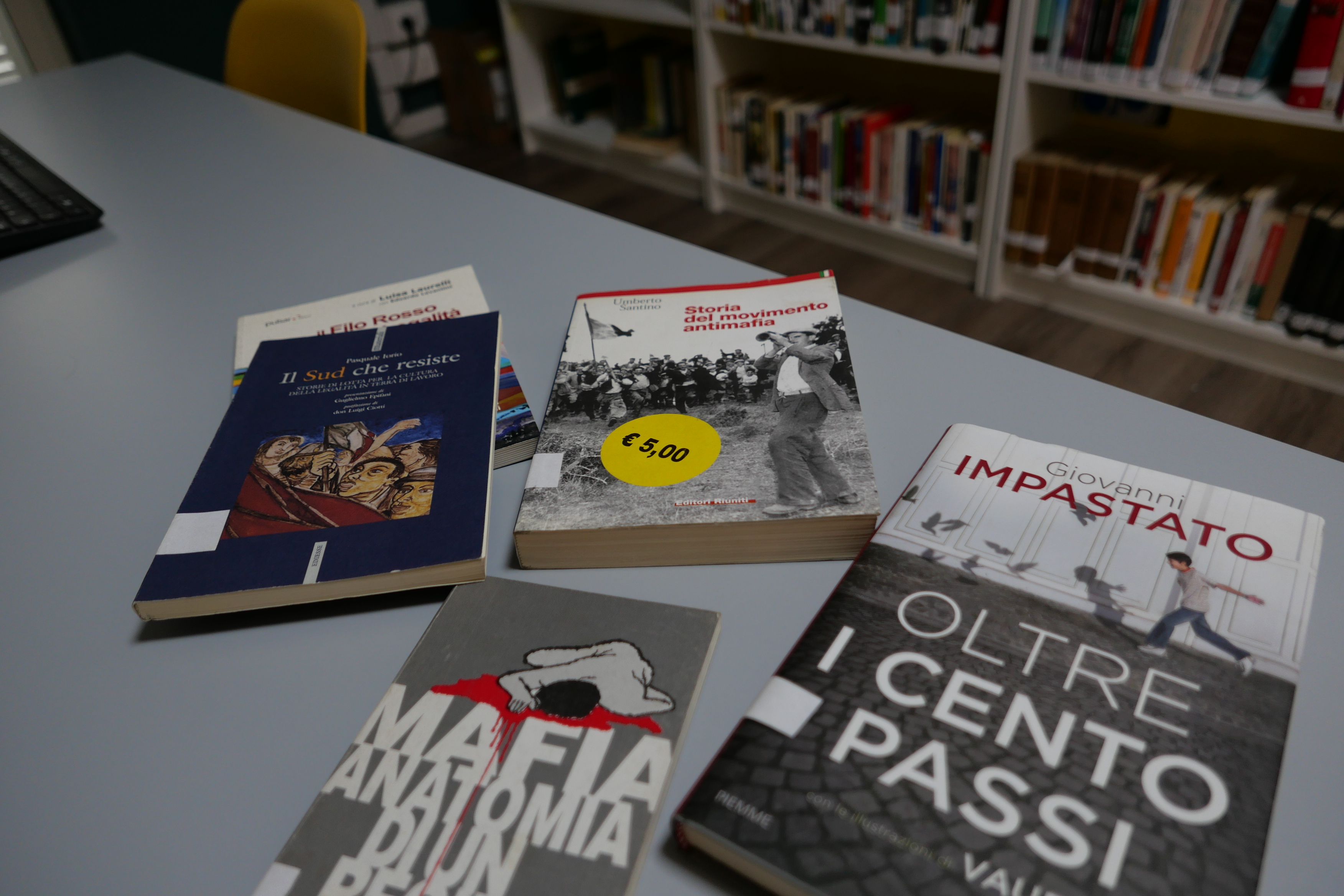

Libraries and documentation centres designed to share resources to promote the culture of legality and the history of the anti-mafia have been installed in Quarto Piano in Sarzana, in la Casa Don Diana, in the cooperative “On the lands of Don Peppe Diana” in Castel Volturno, and in various other places. It is common for school kids or scouts in the area (of which there are a large number of in Italy) to come and visit for a school trip.

The spillover effect

Politically, these places are also there to promote a discourse that runs counter to the beliefs conveyed by the mafia (and by the sometimes complacent media and cultural productions). It is one of the most compelling aspects of what USBC can do for society.

And it is one of the most defended principles championed by all the anti-mafia participants: changing the mentality. There are actually very strong philosophical values that can be associated with successful projects.

By looking to make a positive impact in a place where negativity has thrived, it marks an expression of resilience and a means of “healing” in relation to the “evil” which has been caused by the criminals. “Before I lived a life of crime, but now I am part of the law”, recalls Gaetano Paesano, a former "little hand" in the smuggling business in Naples, who found a job in the Al di là dei sogni cooperative, after his jail sentence. “My parents and friends are happy, except those who are ignorant and are stuck in their old ways”. What better way to redeem myself than to work in a confiscated property?”, he asks.

In the centre of Genoa, former flats used for smuggling, prostitution or rented to Romani families by “unscrupulous landlords” were transformed in social housing.

And it is also a reversal of values between the strong and weak. “To help the weakest is also to help mafia victims. Because the mafia thrives on poverty”, explains anti-mafia activist in Genoa, Davide Ghio. That is why you see so many projects aimed at helping disabled people, migrants, troubled teenagers, former prisoners, long-time unemployed people, etc.

“Before, journalists would come up with he idea that Casal di Principe was Camorra’s territory, saying that we were all corrupt and under the law of silence. This discourse has changed in the last few years. They are interested in the process of change and the path towards redemption which is becoming stronger and stronger. It is now Don Peppe Diana’s territories and no longer Camorra’s”, notes Tina Cioffo.

Finally, each successful project sends a message: “There is a ‘spillover’ effect. When things become reality, it shows others that it is possible to believe that it can happen”, highlights Mauro Baldascino. In the entrance to Quarto Piano, a golden book keeps track of the enthusiasm with which each visitor leaves. Just maybe making them believe that a similar change is possible in their own town.

This article is the second of a three-part series, "New Landlords: when Italian civil society moves in with the mafia".

[Coming up, part 3 examines the issues faced by the social usage of confiscated mafia property projects.]

This project has been carried out in collaboration with researcher Fabrice Rizzoli within the framework of the research project COESO(Collaborative Engagement on Societal Issues) a point of convergence between human and social sciences and participative research. COESO is coordinated by the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales and financed by the European research programme Horizon 2020.

To find out more information on what goes on behind the scenes, visit: https://usbc.hypotheses.org/

Cover photo: The Pas à Pas association in Genoa. ©Mathilde Dorcadie

Translated from « Ceci n’est pas une devanture, c’est un bien confisqué, une ressource de la communauté » (2/3)