The Ukraine and the EU: not happening says Russia

Published on

On 28 November, the association agreement between the EU and Ukraine was discussed at the Vilnius summit in Lithuania. It was an exciting prospect for the European Neighbourhood Policy. Except Russia had different ideas. With threats, pressure and blackmail, the Kremlin pulled out techniques from a bygone age to keep its little brother in its pocket

Closer ties between Europe and Ukraine have opened a whole new can of worms. Despite this unique opportunity to work on values such as democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, EU member states were split as to how to act towards Viktor Yanukovych, the loquacious Ukrainian president. However, little by little, pragmatism gained momentum in Brussels. Eventually, Ukraine opened the door to compromise, contemplating allowing Yulia Tymoshenko to seek medical treatment in Germany.

THREATS AND INTIMIDATION

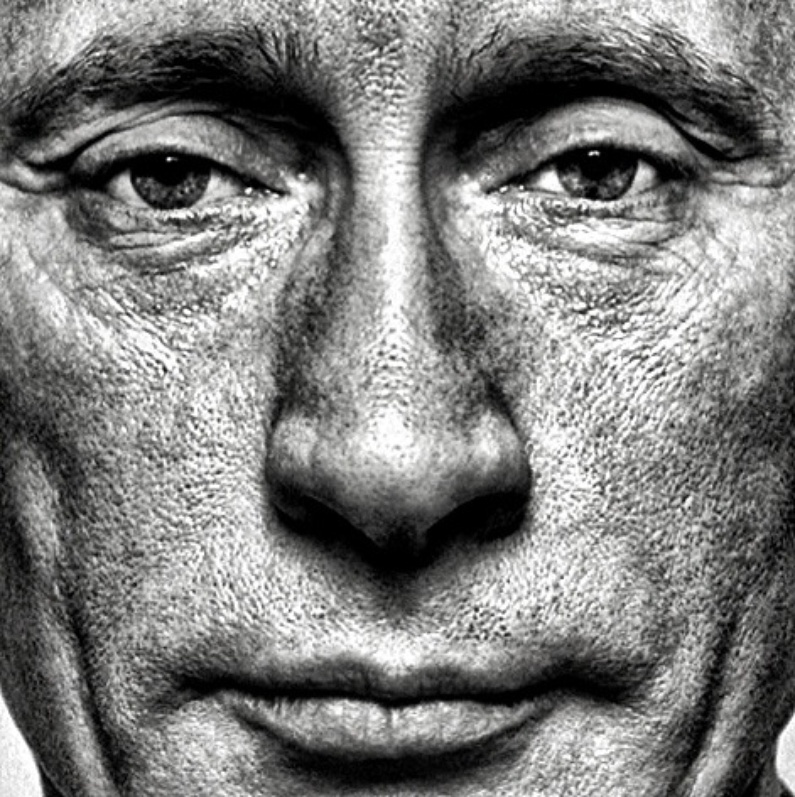

Apart from the positive social impact that an agreement would have on Ukrainian society, the geostrategic benefits are obvious. Better relations with a country such as Ukraine would greatly strengthen Europe's position in a region where Russian hegemony is largely unchallenged. Although the idea of an agreement with Ukraine was gaining ground among European heads of governments and states, another insoluble obstacle reared its Slavic head as the Vilnius summit approached - Vladimir Putin's vicious aversion to closer links between Ukraine and the West. On the contrary, the Kremlin wants Kiev to become fully integrated into its own customs union, which Belarus - considered Europe's last dictatorship - and Kazakhstan have already joined.

The Russian president is standing his ground and will not back down. His main weapon is, of course, gas. Ukrainians are totally dependent on Russian energy, which they buy at an arbitrarily high price. So the tap turning off is a major fear for Ukraine. What's more, Vladimir Putin has exercised his influence over his counterpart, Viktor Yanukovych, implying that he will lend his support to one of Yanukovych's opponents in the next presidential election, due in early 2015.

A THREAT TO EUROPE

In more concrete terms, Moscow has given Ukraine a taste of the commercial sanctions it would suffer if it did form an agreement with Europe. For the last few weeks, the Russian border has been closed to the chocolate manufacturer Roshen, on the pretence of hygiene concerns. If it was expanded to include other Ukrainian products, this kind of restriction could have devastating consequences: Russia buys 25% of Ukrainian exports. This approach has already been used against Lithuania, an EU member, the summit's host, and a strong supporter of an association agreement with Ukraine.

Customs controls imposed on Lithuanian milk imports have become intolerably strict as 28 November approaches. Even worse, the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, to the west of Lithuania, has stocked up on gas. Are they preparing for the Vilnius pipeline to be cut? Dalia Grybauskaité, the president of Lithuania, considers this a plausible hypothesis. Even if it turned out that real economic and energy sanctions were difficult to put in place against Lithuania, with its support from Brussels, the possibility was very real for Ukraine.

Anxious not to offend its troublesome neighbour and, unavoidably, business partner, Ukraine capitulated one week before the summit. In the face of Putin's actions, Viktor Yanukovych made the safe choice and suspended the association agreement with the EU. However, this geopolitical victory for the Russian president, who has once again showed himself to be more skilful than his European counterparts, may not be long-lived. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians in favour of the agreement have taken to the streets to protest, opening the door to signing the agreement at a later date and making Ukraine's official entry into the Russian customs union unlikely.

Translated from L'Ukraine dans l'UE : Poutine ne lâche pas de l'est