The emotional ice age

Published on

Translation by:

vicki bryan

vicki bryan

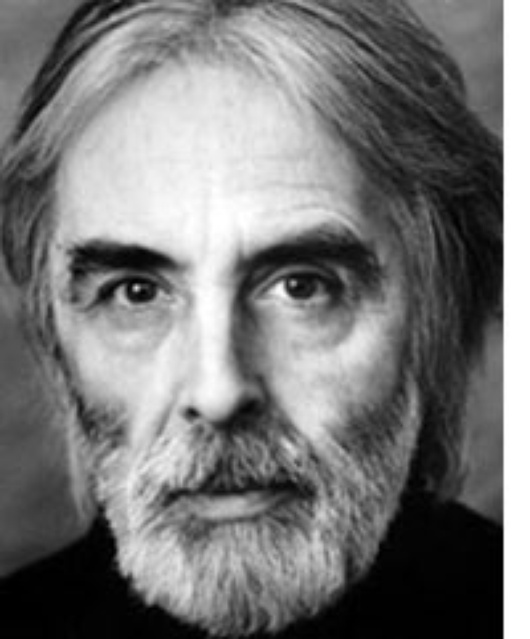

Films by Austrian director Michael Haneke pose unsettling questions which he refuses to answer, and which you’ll never forget

Whoever managed to sit through until the end of the film ‘The Seventh Continent’ would have sat in stunned silence for several minutes in front of a crackling screen. The film closes with the image of a father, who has taken poison, waiting for his life to end, while next to him his wife and child lie already dead. The screen cuts to black to signify death, with the collective suicide of the family symbolising release from a moribund existence. The audience are left to return, somewhat disturbed, to their own lives in which symbols of middle-class life, such as a food processor or electric garage door, have suddenly become metaphors for inhumanity.

Whoever managed to sit through until the end of the film ‘The Seventh Continent’ would have sat in stunned silence for several minutes in front of a crackling screen. The film closes with the image of a father, who has taken poison, waiting for his life to end, while next to him his wife and child lie already dead. The screen cuts to black to signify death, with the collective suicide of the family symbolising release from a moribund existence. The audience are left to return, somewhat disturbed, to their own lives in which symbols of middle-class life, such as a food processor or electric garage door, have suddenly become metaphors for inhumanity.

As senseless as reality

This ‘glaciation of emotions’ in our post-modern consumer and media society is the main theme in the works of Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke. It is not entertainment or distraction that cinema-goers will find when they go to watch such films as ‘Benny’s Video’, in which a teenager films himself slaughtering a friend with a stun-gun, or ‘Funny Games’, an ice-cold horror film parody which catches the viewer out at his own voyeurism and then throws him into a nightmarish world that is just as meaningless as life itself. “I wanted to show that, in the end, not all is right with the world – your friendly neighbour is just as likely to turn around and kill you as the Arab terrorist that the whole world is so afraid of at the moment”, explains Haneke, thereby prompting us to think about ‘reality’ as portrayed by the media and our own desire for tension and shock. In contrast to the plot of a typical thriller, those who go to see Haneke’s films are not rewarded with a happy ending, in which good wins over evil and people die for a reason. At the end of ‘The Piano Teacher’, based on the book by Nobel Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek, Isabelle Huppert stabs herself in the stomach and staggers, injured, out of shot – her suicide is a failure, just as all of her other actions that were led by emotion. In his films, the thin veneer of life is scratched away and suppressed feelings are released, with the result that the freed person will strike the person who comes along next, or even themselves. Death and suffering remain meaningless, incomprehensible and inevitable.

Refuge in France

The eternal idyll that is Austria, with its gleaming alpine landscape that hides a suppressed past, forms the starting point for the incisive criticism of society by such authors as Thomas Bernhard, Elfriede Jelinek, and filmmakers such as Haneke, none of whom seem to feel any sort of pleasure for their own country. For Haneke, however, this glaciation of emotions is not just an Austrian phenomenon. After the presentation of ‘The Seventh Continent’ at Cannes, where Haneke is a regular guest and most recently caused a stir with ‘The Piano Teacher’, a journalist asked him whether life in Austria really was that bad. “Since then, I’ve tried not to link my films to particular places. They should have relevance wherever they’re shown.”

Haneke, who is so critical of his own country, has had far more success in France, the home of cinema, than in his own petit-bourgeois homeland. His last film “The Time of the Wolf” is a French production and boasts French stars such as Patrice Chereau, Beatrice Dalle and also Isabelle Huppert. In the film, people are left to fight for the most basic of things, such as water, food, or shelter, following an indeterminate catastrophe. It’s at this time of need that they reveal their true colours – to them, other human beings become wolves. Once again, Haneke avoids the comfortable plot progression of a typical Hollywood film whereby the story is resolved following a dramatic climax and the viewer can neatly file away the satisfying horrors of the film in the folder marked ‘consumer goods’. Rather, there is no answer, no meaningful end. All that’s there to begin with and all that’s left is life itself, and the disturbing aspects of the film will take root in the minds of the viewing public. Or, as Haneke puts it: “Films that deal with the horror of society can only ever be formulated as questions. And if a question is asked insistently enough, then the viewer will not forget it as quickly as an answer that has reassured him.”

Haneke’s new film, due to be released in 2005, is called ‘Hidden’. Again, it is a French production, with French actress Juliette Binoche in the leading role, which, against the backdrop of the Algerian war, looks at the question of personal guilt and responsibility. No doubt we shall be leaving the cinema feeling somewhat disturbed.

Translated from Emotionale Eiszeit