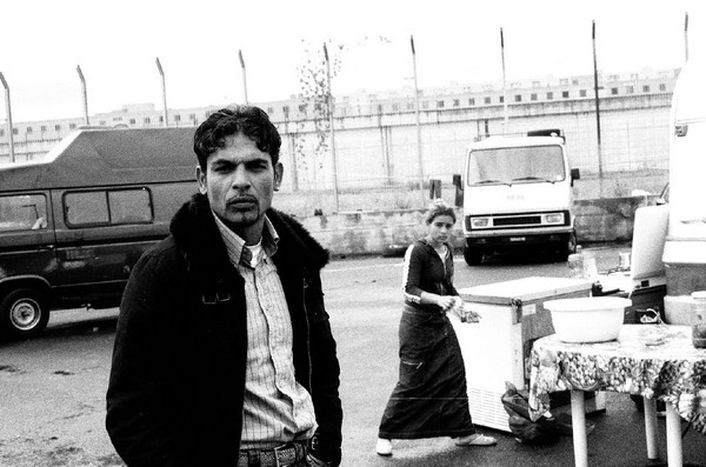

Roma in the Ponticelli district, Naples, speak after the fire

Published on

Translation by:

Mary MaistrelloThe intolerance of the population towards the nomads, who had been living for years on the periphery of the city, has become ever violent, supported by the popular and racist propaganda of the Lega Nord (northern league) political party. We try to understand what is left after the lynchings, the fires, the vigilantes and forced evictions

When it rained heavily in Ponticelli, the noise of the water hitting the shack roofs could be heard even in the city centre. Of the thirteen Roma camps which stood on the periphery of Naples in May 2008, only three remain, maybe four. The flight of the 'gypsies' feels very natural round here: away with the caravans, shacks destroyed, an end to the noisy sheet-metal which annoyed the nearby inhabitants.

Sent away

'We have sent them away,' says Gianni, in answer to directions for Virginia Woolf Street. 'If you’re looking for the Romanians, you won’t find anything. We’ve sent them away. We burned everything after they fled.' There was little in the national papers regarding the fire in May. Of how, one by one, children, men, the old and women were herded out of their homes and forced into the woods. Some only went a short way, waiting for the anger of the Italians to subside, only to see them return at night, instead, to torch everything which they had not destroyed in the afternoon.

'We have sent them away,' says Gianni, in answer to directions for Virginia Woolf Street. 'If you’re looking for the Romanians, you won’t find anything. We’ve sent them away. We burned everything after they fled.' There was little in the national papers regarding the fire in May. Of how, one by one, children, men, the old and women were herded out of their homes and forced into the woods. Some only went a short way, waiting for the anger of the Italians to subside, only to see them return at night, instead, to torch everything which they had not destroyed in the afternoon.

From his ‘kampina’ - the name for caravan often used by Romanians - the signs of the fire of last 13 October on the campsite under the bridge of the A3 Naples-Salerno motorway are still visible. 'They want to send us all away. All of us. They don’t want us anymore. They shout us down: Go away! Go away! They have started calling me 'child snatcher' again. They even called my father that, but then they stopped. We were doing well in Naples.' In Naples they were doing well, he repeats time and again. They were doing well until a Roma girl was accused of trying to snatch a child. After that episode in Ponticelli on 10 May 2008, the intolerance of the population towards the nomads, who had been living for years on the periphery of the city, has become more and more violent, supported by the popular and racist propaganda of the Lega Nord (northern league) political party.

'Security package': police records and evictions

Since last spring, it has been a round of safety measures, evictions and police records in the whole of Italy, from Milan to Foggia, from Naples to Rome, in decrees and initiatives taken at administrative level, and which seem to find popular consensus. Nico holds his daughter Sara in his arms - 'Sara is the mother of the Romanian people' – whilst he tells of his life as a gypsy during the past six months: 'They wanted to take our children’s fingerprints – why? They are children, they live with us. We all live in the same way, we don’t exploit our children.' Sara holds her hand out, palm facing upwards: it’s the sign of the manghel (Roma word for 'beggar'). She's only one year old and she already knows how to beg. She is given a small coin, but she puts it on the table and points to a pen instead. 'We live from charity. If we could work, if someone would give us work, we wouldn’t beg. But maybe, even if we had work, we would beg anyway: that’s how Roma are. That’s how my grandfather’s grandfather grew up, and my grandfather, and my father. That’s how my children are growing up. Holding out your hand to ask for help is not stealing. Living with rats, without a bath and with lice crawling on you is not fun. When you look at me, do you see some rich person having a laugh by living like beggar?' He pronounces the word 'beggar' in a typical Neapolitan accent.

Nico knows well what people say about the nomads: they pretend to be poor, but are really very rich. 'There are those who have money. There are delinquents, there’s loads of them in Naples. And even Neapolitan thieves are called zinka’r (Neapolitan for 'gypsies'). There are many or there are few. I don’t know. I know that often I have nothing to eat, that I can’t wash myself, that I’ve been beaten up, that people look at me in a bad way, that they look at my wife and my girls like they are guilty. If Anna goes out begging and is late getting back, I go and look for her: here we go, I think, they’ve arrested her for exploiting the children and now they’ll take my girls away.'

'Maybe, even if we had work, we would beg anyway: that’s how Roma are'

Before entering the kampina, Anna and her daughter take their shoes off, Julia puts the coins in front of her father and leaves the cornets that she has not managed to sellon a chair. Then she smiles. Nico gets up to see what is happening outside. 'Another six are leaving,' he says. A small van is going down the street which leads to the centre, full of packages and people. 'They’re going back to Romania. They’ll take a coach, which is cheap. The coaches are organised by the Atlassib travel agency, spread throughout a large area of Europe with Bucharest as the destination. In Italy, every night at 11.30pm, coaches leave from Taranto, crossing the peninsula and dropping off dozens of care workers and Roma between Hungary and Romania. 'I’m not going back to Costanza (a Romanian city on the Black Sea - ed). I don’t have the money to pay for four tickets and I don’t want to anyway. (Italian prime minister) Silvio Berlusconi shouldn’t be sending us to Romania. He should be bringing back the Italian (entrepeneurs) who are stealing in Romania, by stretching their arms like this,' he says, pointing his index finger forwards and his thumb upwards to look like a gun: 'boom'.

Translated from Il problema rom in Italia: nel quartiere di Ponticelli dopo i roghi