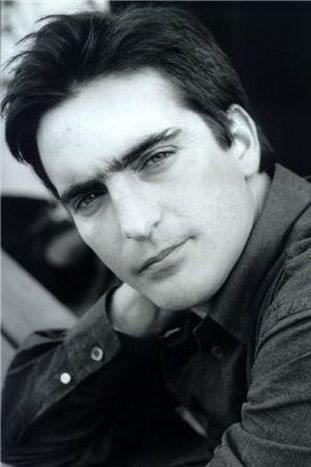

Portuguese singer Camane: 'Nobody in my generation was listening to fado music'

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)While ‘folk music‘ isn’t too popular in most countries, the Portuguese fado attracts a wide range of generations - at least in its home country. The masculine figurehead of a new generation of fadistas, 44, speaks about the genre’s roots

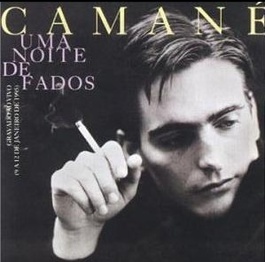

Carlos Manuel Moutinho Paiva dos Santos aka Camane began his career early on in 1967. He was seven when he had his first exposure to the melancholy music on his parent’s old records. Just five years later he won his first amateur singing competition. At seventeen, he became the professional fado singer that he had always dreamed of being. To follow were gigs in the clubs of Lisbon – he was born just outside the Portuguese capital – to guest appearances on various musical productions. Today Camané is one of the most successful figures of a genre which presents the best insight into Portuguese culture.

Carlos Manuel Moutinho Paiva dos Santos aka Camane began his career early on in 1967. He was seven when he had his first exposure to the melancholy music on his parent’s old records. Just five years later he won his first amateur singing competition. At seventeen, he became the professional fado singer that he had always dreamed of being. To follow were gigs in the clubs of Lisbon – he was born just outside the Portuguese capital – to guest appearances on various musical productions. Today Camané is one of the most successful figures of a genre which presents the best insight into Portuguese culture.

Fado: Portuguese ambassador?

‘Of course emotions such as love, lust and hope are everywhere,' explains the 44-year-old, ‘but the way you express them differ from one another when it comes to tempo or rhythm. Argentinians have tango, the Spaniards have flamenco and we Portuguese have fado.’ The word ‘fado’ itself translates to ‘fate’, which is exactly how the music sounds. A wistful voice pines through the music which is accompanied by a rhythm guitar as well as a Portuguese guitar. Songs are usually about goodbyes, sadness, pain and eternally about waiting and hoping.

Even today experts disagree on the origins of fado. Some historians point to comparisons with North African music and see the genre as a relic of Moorish rule. Others believe there is a Brazilian elements of Lundum, the music of the African slaves, to the music and believe it grew in the nineteenth century. What is sure is that fado got more and more successful in the poorest areas of Lisbon. Merchants, vagrants and prostitutes purportedly sang it in their local taverns. This popularity is what makes the genre, says Camane. ‘Fado was always a very urban kind of music,' he explains. 'At the beginning the songs told short stories of people’s lives at the time. Sometimes even gossip was spread that way. Later fado was used more to overtone famous poems.’ The tradition still stands today. The spectrum of works runs from Luís de Camões and Fernando Pessoa to Manuel Alegre.

Even today experts disagree on the origins of fado. Some historians point to comparisons with North African music and see the genre as a relic of Moorish rule. Others believe there is a Brazilian elements of Lundum, the music of the African slaves, to the music and believe it grew in the nineteenth century. What is sure is that fado got more and more successful in the poorest areas of Lisbon. Merchants, vagrants and prostitutes purportedly sang it in their local taverns. This popularity is what makes the genre, says Camane. ‘Fado was always a very urban kind of music,' he explains. 'At the beginning the songs told short stories of people’s lives at the time. Sometimes even gossip was spread that way. Later fado was used more to overtone famous poems.’ The tradition still stands today. The spectrum of works runs from Luís de Camões and Fernando Pessoa to Manuel Alegre.

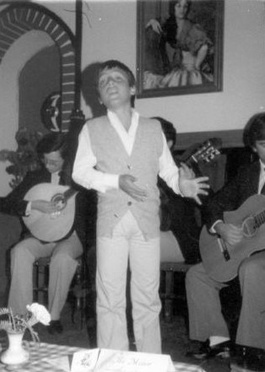

This close link between the music and national identity was also one of its greatest stumbling blocks for a long time. As fado conquered the salons of the finer society and slowly emerged as an international ambassador in the 1930s, it also became an increasingly political instrument of the then-dictator Antonio Salazar. Personally he wasn’t a fan of the ‘maudlin’ style of the music, but he knew well that he could stylise fado as a symbol of the Portuguese nation. The censorship that ensued meant that the open critical nature of the music now projected a conservative world view and a ‘poor, but happy mentality’. The music’s association with the fascist system was so heavy that many young ashamed Portuguese ended up distancing themselves from it towards the end of the dictatorship in 1974. Camane remembers those not-so-good old days well. 'I was seventeen and hanging out in fado clubs when it was ‘music for old men‘. The men there were at least seventy or older. I was laughed at. Nobody in my generation was listening to fado music.'

Modernity versus tradition

Fado’s status has changed again today thanks to the diversity which makes up the genre. The singer Mísia added classical instruments including the accordion, piano and violin, whilst bands such as A Naifa and Donna Maria remix fado songs with electronic beats. Camane himself is famous for leaving the traditional terrain. For example, he collaborated with the group Humanos in 2004, releasing a popular album of songs in homage to pop legend António Variações. Whilst the swing between tradition and the modern seems indispensable to be successful today, Camane emphasises that it is a balancing act. ‘Fado has to be recognised as fado, always. Tradition is important, yet the music has to develop otherwise you don’t experience it. The important thing is to develop it from the inside to the outside, naturally. You can’t force such a thing. The most important thing in fado is and will always be authenticity.’

No matter what the music sounds like, it will always be connected by that red line of saudade, or the Portuguese concept of longing. That doesn’t mean ‘sadness’ though; the feeling is too complex, Camané finishes. 'Fado has this paradox about it. It makes us cry when its joyful and it makes us smile when it sad. It has this power to get rid of sadness and it can change your life. Fado helps us experience ourselves as individuals as well as a people. That’s the great power of this music.’ It’s also thanks to this power that fado remains an omnipresence on the Portuguese scene today.

Images: ©camane.com; © Camané bei MySpace/ videos: (cc) Youtube

Translated from Fadosänger Camané: eine Trauer, die guttut