Paula Bonet: "We're Not Allowing Ourselves to Enjoy or Suffer from the Here and Now Anymore"

Published on

Translation by:

Samantha KelloggHalfway between nostalgia and optimism, blue's tranquility and red's strength trap us in the creative universe of Paula Bonet, the Valencian illustrator that has found the best gallery for getting closer to the public is the Internet. We talk with her about armless houses, paper prawns and her new book, written and illustrated entirely by her.

Contemplating an illustration of the famous Paula Bonet means taking a look at yourself and, on ocassion, staying to reflect. Standing still in front of a mirror in which a woman mends a heart, her heart, asking it never to end and another woman knots another's reddish hair, also long but darker, that she just found, by accident, at home in the shower. "The quantity of images that we consume daily and the speed at which everything happens doesn't allow us to stop for a moment and enjoy - or suffer, or simply be conscious - of the here and now," claims Paula Bonet (Vila-real, 1980), who just published her first book, narrated and sketched entirely by her.

Contemplating an illustration of the famous Paula Bonet means taking a look at yourself and, on ocassion, staying to reflect. Standing still in front of a mirror in which a woman mends a heart, her heart, asking it never to end and another woman knots another's reddish hair, also long but darker, that she just found, by accident, at home in the shower. "The quantity of images that we consume daily and the speed at which everything happens doesn't allow us to stop for a moment and enjoy - or suffer, or simply be conscious - of the here and now," claims Paula Bonet (Vila-real, 1980), who just published her first book, narrated and sketched entirely by her.

While she worked with images and text upon the same medium some time ago, "trying to make them need each other", in What you should do when The End appears on the display (Lunwerg Editors, 2014), has finally given free reign to her two artistic passions to "weave something less immediate, more cultivated, where illustrations and literature merge and create a more conscious whole," she relates. "This work may have an implied narrative liberation," the author concludes to the magazine Cafébabel.

Armless houses, paper prawns and oceans of grief

The 0.5 millimeter lead, the Chinese ink or the brush-strokes of aquamarine and red watercolor, that singled out Bonet's style so much, coat each one of the forty stories that this book harbours.

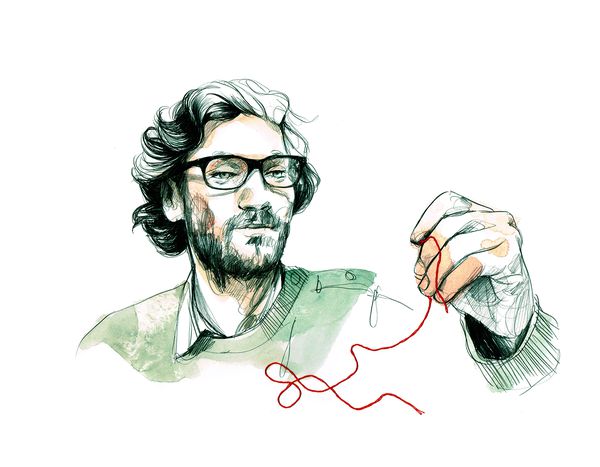

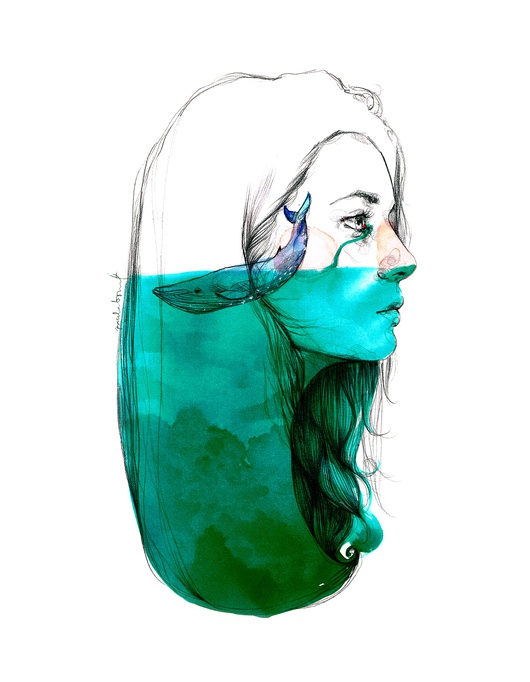

Some stories are nostalgic, like the one about that house which appears to have amputated an arm because you are no longer, others are ambiguous like the one where a woman who got used to asking for a table for one and that finally noticed, what a face and what a smile, the person sitting in the opposite, empty seat had, or more witty and salty stories like the one with that boy that liked prawns so much, he ended up eating a paper one. Bonet confesses that she has a tough time deciding between her own drawings, maybe "making an effort" and drifting by her "most private" work, she could select the illustration for the male character in How to cross a river (story number 12). It already personifies "a friend that disappeared early" and that, whenever she can, likes to remember. The woman flooded by the ocean and the animals that inhabit it, in the piece, Weeping oceans that stay inside you (story number 36) is another of her favourites. "This illustration started a new period in my work," she explains. Despite her artistic training having been concentrated in oil painting and etching - hand engraving, lithography and wood engraving, it was the year 2009 when she threw herself into experimentation in the field of illustration. The canvases expired for her. "Making pictures was my way of communicating with somebody and I needed to buy time. I couldn't spend three days on one idea that expressed something that seemed important to me at that moment," she points out.

Some stories are nostalgic, like the one about that house which appears to have amputated an arm because you are no longer, others are ambiguous like the one where a woman who got used to asking for a table for one and that finally noticed, what a face and what a smile, the person sitting in the opposite, empty seat had, or more witty and salty stories like the one with that boy that liked prawns so much, he ended up eating a paper one. Bonet confesses that she has a tough time deciding between her own drawings, maybe "making an effort" and drifting by her "most private" work, she could select the illustration for the male character in How to cross a river (story number 12). It already personifies "a friend that disappeared early" and that, whenever she can, likes to remember. The woman flooded by the ocean and the animals that inhabit it, in the piece, Weeping oceans that stay inside you (story number 36) is another of her favourites. "This illustration started a new period in my work," she explains. Despite her artistic training having been concentrated in oil painting and etching - hand engraving, lithography and wood engraving, it was the year 2009 when she threw herself into experimentation in the field of illustration. The canvases expired for her. "Making pictures was my way of communicating with somebody and I needed to buy time. I couldn't spend three days on one idea that expressed something that seemed important to me at that moment," she points out.

Between tranqulity and strength

Almost immediately, the strokes that Paula Bonet's work demonstrates so much of started to appear, the use of red hues, that she herself associates with blood, vitality, and strength: or the tact of each detail, like the care with which she outlines her protagonist's hair. However, she maintains that she has a tough time theorising about her creations, yet, the majority of endings make up more a part of the shape than the contents. "When I draw I try to tell a story, the theme of hair care, for example, it's all anecdotal," she notes.

When the people at Vila-real publish one of her pictures on social networks, reactions are immediate. Earlier this week, 814 likes three seconds after sharing the sketch for a poster on her Instagram account. "The Internet isn't the best art gallery that I've been able to exhibit my work in, but it is what has brought me closest to the public. The Web has gotten all the galleries' structure, just as I understood it when I studied Fine Arts, to totter and it was forced to reinvent itself."

It's this new generations of creators, Paula Bonet specifically emphasises, that could predict a paradigm shift in the essence of Art. The generation that could, perhaps, put an end to to the elitism that has always been linked to this discipline

Translated from Paula Bonet: "Ya no nos permitimos disfrutar o sufrir del aquí y ahora"