Paris suburbs: 'place of exile'

Published on

Translation by:

jessica adler

jessica adler

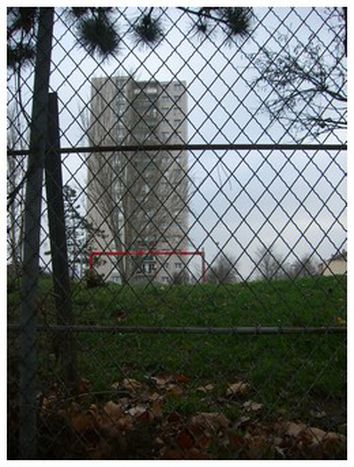

'Banlieue' is the colloquial reversal of 'lieu du ban', literally, 'place of exile'. In the French suburbs, out of work labourers are holed up in prison-style buildings, along with their children, to whom they pass on their despair

In the 1970s French factories needed labour, and immigration from France's former colonies provided the main, and very cheap, source of this. It was then that social housing reached its peak: cold, high-rise buildings in peripheral locations with no shops provided a storehouse for these individuals, who today swell the lists of unemployed, and who brought their families with them before the borders were closed in 1974.

Today, the lack of investment and the marginalisation of these concrete limbos are the fruits of a government plan, the consequences of which were not anticipated. We talk about these consequences and their causes in Les Canibouts, a social centre situated in a particular banlieue: Le Petit Nanterre.

Le Petit Nanterre

This suburb suffers from a double isolation: the river and train tracks separate its inhabitants (9, 000) from the rest of Nanterre's inhabitants (76, 000). Its neighbours are La Defénse, Paris's business district, and Neully sur Seine - its most luxurious suburb - where Sarkozy governed as mayor before arriving at the Elysee as interior minister and today, president. It was there he described the population of suburbs such as Nanterre racaille (scum, rabble).

Nanterre Hospital is known  for being the place where the homeless of Paris used to spend the night when sleeping on the streets was forbidden. And now that it is allowed, it is in the banlieue that young people - according to the politics of zero tolerance - are not allowed to gather in the doorways of houses. With this, it is claimed that episodes such as the burning of a bus in Nanterre at the hands of hoodies on the first anniversary of the riots of 2005 will be avoided.

for being the place where the homeless of Paris used to spend the night when sleeping on the streets was forbidden. And now that it is allowed, it is in the banlieue that young people - according to the politics of zero tolerance - are not allowed to gather in the doorways of houses. With this, it is claimed that episodes such as the burning of a bus in Nanterre at the hands of hoodies on the first anniversary of the riots of 2005 will be avoided.

That is where the socio-cultural centre 'Les Canibouts' is located. Like so many other social initiatives it is self-financed with a very low level of income - the fruit of token charges for certain activities - and highly dependent on outside help. In this case, outside help consists of the CAF ('Caisse d'Allocations Familiales' - the local body that deals with all things related to allowances and benefits). This CAF provides help with hiring the building, the DDJS ('Regional Management for Youth and Sports'), and the local council. Marjorie Vignon, a social worker in Les Canibouts, believes that 'there is a lot of bureaucracy in the application process and few guarantees of getting anywhere, which means that it's difficult to make long-term plans.'

Marjorie is originally from Brittany,  and is responsible for children aged between six and twelve: 'It's a balance between the demands of the citizens and a few contributions which do not cover these demands'. Many initiatives fail as a result of a lack of subsidies and to avoid this they work with the district's other social centre, the Valérie Méot centre, which specialises in families. With the development of the quarter a priority, they organise the Parents' Café - with debates on topics such as children's education and local politics - or the Christmas party, where this year cous-cous was on the menu.

and is responsible for children aged between six and twelve: 'It's a balance between the demands of the citizens and a few contributions which do not cover these demands'. Many initiatives fail as a result of a lack of subsidies and to avoid this they work with the district's other social centre, the Valérie Méot centre, which specialises in families. With the development of the quarter a priority, they organise the Parents' Café - with debates on topics such as children's education and local politics - or the Christmas party, where this year cous-cous was on the menu.

Anti-ghettos

Like Christmas and the cous-cous, religions co-exist in the banlieue although it was Muslims who found the finger of blame pointing at them for the disturbances. Far from applying prejudicial models, sociologist Loic Wacquant uses the term anti-ghetto to affirm that 'European banlieues are heterogeneous. The marginalisation of their inhabitants does not stem from race or ethnicity; but rather from social class.'

In fact, the layout of the French suburbs  hinders neighbourly and community relationships that could, for example, encourage religions to develop. They are designed in a way that makes it difficult for immigrant workers to mix and to enjoy leisure time, encouraging them to save in order to become future homeowners. In neighbourhoods of strangers the perpetual police presence so characteristic of the Republic has more justification.

hinders neighbourly and community relationships that could, for example, encourage religions to develop. They are designed in a way that makes it difficult for immigrant workers to mix and to enjoy leisure time, encouraging them to save in order to become future homeowners. In neighbourhoods of strangers the perpetual police presence so characteristic of the Republic has more justification.

On this subject, Ludovic Alexandre - co-ordinator of adolescents in Les Canibouts - speaks with a sense of irony, standing next to the window of one of the centre's classrooms: 'Where are the burning cars and the aggressive youths?' He channels the creative energy of his young people into theatre, slam and video workshops, and these fund nature trips on weekends and during the holidays.

Ludovic laments the fact that the abuse of police power and lack of state attention are united with 'the vision that the media gives of the banlieues' by endlessly broadcasting images of violent reactions and injured police officers, without dedicating front pages to the beatings given to young banlieusards - shown on Youtube - or to the origins of the protests. These protests are the subject of the book Scum? ('C'est de la racaille ? Eh bien, j'en suis!', by Allési Dell'Umbria) about the riots of autumn 2005, in which a witness states, 'if there were monuments, cars wouldn't have been burned.'

The car is a symbolic element in an era of postfordism and unemployment. In addition, the isolation of some banlieues is such that it is difficult to leave them without one. This is the case in Clichy sous Bois, protagonist of the 2005 riots: there is no metro or train station. It is the poorest of all the banlieues, with unemployment at 45%. The fires are a response to an attempt to focus people's eyes on the suburbs, and to make change happen there.

The car is a symbolic element in an era of postfordism and unemployment. In addition, the isolation of some banlieues is such that it is difficult to leave them without one. This is the case in Clichy sous Bois, protagonist of the 2005 riots: there is no metro or train station. It is the poorest of all the banlieues, with unemployment at 45%. The fires are a response to an attempt to focus people's eyes on the suburbs, and to make change happen there.

Containment by the police is not a solution

Containment by the police stops the situation becoming explosive, but it does not improve it. The proof is the disturbances that occurred in the autumn of 2007, motivated by the death of racaille youths in a police chase. 'This growing police presence coincides with the restrictions on asking for social help,' says Marjorie.

Conscious of the fact that exclusive capitalism needs pockets of poverty, she also explains that 'most of the activities are tools for equality of opportunities', such as courses in literacy, French or IT. There is also a creche, cultural excursions, free legal advice and help seeking work. 'And while children and women attend the centres, men rarely participate,' laments Marjorie, assuring us that they promote mixed activities.

Conscious of the fact that exclusive capitalism needs pockets of poverty, she also explains that 'most of the activities are tools for equality of opportunities', such as courses in literacy, French or IT. There is also a creche, cultural excursions, free legal advice and help seeking work. 'And while children and women attend the centres, men rarely participate,' laments Marjorie, assuring us that they promote mixed activities.

In Marjorie's banlieue and others, people are aware of the increase in imprisoned people, caused, according to the French Justice Ministry, 'not by the increase in criminality, but by penal policies.' For example, between 1996 and 2006, sentences of 20 to 30 years of prison multiplied by 3.5. According to the same ministry report, 'most of the new prisoners are men, young and socially unintegrated.' The situation has also been described by the French prison social workers Union as 'saturated.'

(In-text photos: Marta Palacín Mejías)

Translated from Banlieue: el lugar del destierro