Once upon a mosque in Athens: illegal garages but not for raves

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)Around 700, 000 residents of Greece’s 11 million people are muslims. The figure is not exact since the government doesn’t make it easy for the community – essentially, the Greek capital is the only European one not to have a functioning mosque

Muslims have lived in Greece for decades. While many form part of the so-called second generation, meaning they speak the language and behave like other Greeks, they are not official citizens of the Hellenic country. It doesn’t help that the government is denying a petitition for the construction of a mosque.

Neither mosque nor cemetery

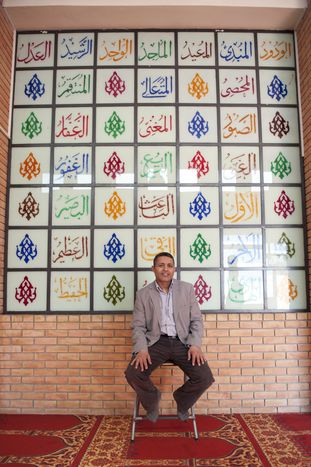

‘We got an offer to fund the mosque from Saudi Arabia, but we rejected it,’ says Naim Elghandour, the Egyptian president of the muslim association of Athens. ‘We don’t want to owe them. We want a public space constructed by the Greek government.’ Naim and his wife have spent almost all of their lifetimes here. Naim has even completed military service, but the couple almost always meet obstacles to being completely integrated. Whilst they manage to reach an agreement on the land to build a mosque upon, they realised shortly after that it would be near the airport. ‘It was madness,’ says Naim. ‘Practically no practising muslim could get there five times a day to pray. There wouldn’t be time to get there and back, no money to pay for this trips and no ideal transport method.’ The community found itself back at square one. ‘The governmental bodies told us that it wasn’t their fault, that they were behind building it. It’s true that they’ve never expressly said ‘no’ – they just haven’t really facilitated anything more than their words.’

‘We don’t want to create a ghetto, a society within a society’

The muslim community of Athens does have one cemetery run locally in Komotini, which means travelling to the north of Greece. The costs of moving funerals there and transportation make this a difficult task. It’s advantageous for the local muslim community to have this asset and thus be stronger in unity and Independence, but it’s not something Ana wants for Athens. ‘We don’t want to create a ghetto, a society within a society,’ she says. Various NGOs have advised the couple to take the case to the courts and international tribunals, but they won’t do so. ‘This would be the last straw. If we were suing our neighbours it would humiliate our friends and colleagues. We don’t want that.’

Al Salam, garage mosque

At 9pm, Mohammed Rossa welcomes me for the final prayers of the day in the neighbourhood of Neos Kosmos. Neon signs decorate the area full of Lidos and sex shops with images of girls disrobing and posing suggestively. Paradoxically, carnal temptation stands before the purification of the spirit. Mohammed left Palestine almost two decades ago to come and live in Greece, though he still does not have citizenship. ‘There is always an excuse,’ he says. ‘First they tell you that you need to have spent ten years in the country, then that you need to have a job, then another… My brothers were lucky. They arrived in Greece some years before me and did get citizenship. Others managed it by passing an envelope along under the table, if you know what I mean.’

A former garage underneath a building serves as an illegal mosque in Neos Kosmos. It’s not the only one in the Greek capital, with around one hundred such places. ‘It’s hard to know exactly when you can organise a meetup and prayer service in your own home or premises,’ explains some men waiting in the hall. A large part of the muslim community live in this zone, making it one of the most popular in the city. Inside, 500 people can be welcomed. A small staircase to the right leads to a small zone with various bathroom facilities to follow the ritual of cleansing the body before praying. In the same shabby room, the dead are washed. To the left, a ramp leads to the prayer room, covered in reddish carpets with some excerpts from the Koran and books about islam on the shelves. It could very well look like an authentic mosque where it not for the noise from the roof’s extractor fans. Mohammed and his wife bought this garage in 1993 because they thought it was necessary to create a space like this. They named the first mosque in Greece Al Salam.

Read 'Building a mosque in Warsaw: is it all trouble and strife?' on cafebabel.com

Julie Jalloul, a young Syrian woman who studies journalism at the university of Athens, appears in the middle of prayers. She remarks how unusual she finds it when people she know criticise ‘those immigrants who live there’ without ever really appreciating that she is ‘one of them’ too. ‘I have lived in Greece all my life, I speak it without an accent. That’s why it’s hard for people to believe that I am actually from Syria,’ she says. She is currently working on a website where she can post news from the islamic world of Greece with others.

It’s hard to imagine a future solution to the problem of the mosque just yet. Greek nerves are still frayed as recent protests and the suicide of a pensioner in the central Syntagma square show, as well as the construction of reception centres for illegal immigrants that the government hopes to have in place by 2013. ‘I guess many muslims who recently arrived would prefer to move somewhere else considering how impossible it is to live here,’ says Julia. ‘Those who have been able to lay down deeper roots are probably having to keep living under the radar, practising their religion in hidden mosques.’

This article is part of the fifth edition in cafebabel.com’s 2012 feature focus series on multiculturalism in Europe. Many thanks to the team at cafebabel.com Athens

Images: Colin Delfosse (outoffocus.be) for ‘Multikulti on the ground 'Athens' by cafebabel.com

Translated from Atenas y su (no) mezquita, un oscuro conflicto