New EU immigration directive: ‘policy of shame’

Published on

Translation by:

Kate Stansfield

Kate Stansfield

Will a Romanian in Spain be forced to learn the paella recipe off by heart? The new EU immigration policy has been branded as xenophobic by some of the countries concerned

In the next few weeks, European leaders will officially reach an agreement regarding French president Nicolas Sarkozy's proposal for a common immigration policy. Goodbye to more large-scale regularisations and hello to the possibility of demanding that recent arrivals learn the local language and culture. The vision shared by Sarkozy and Italian premier Silvio Berlusconi takes over from that of Spanish PM Rodriguez Zapatero: will a Romanian in Spain be forced to learn the paella recipe off by heart?

In the next few weeks, European leaders will officially reach an agreement regarding French president Nicolas Sarkozy's proposal for a common immigration policy. Goodbye to more large-scale regularisations and hello to the possibility of demanding that recent arrivals learn the local language and culture. The vision shared by Sarkozy and Italian premier Silvio Berlusconi takes over from that of Spanish PM Rodriguez Zapatero: will a Romanian in Spain be forced to learn the paella recipe off by heart?

Immigration, no return

Immigration is no longer an issue that concerns each member state individually. In 2007, for example, Portugal received 100, 000 Ukrainian illegal immigrants whose position was regularised by the Portuguese government to ease the economic crisis sweeping the country at the time. These 'legalised' immigrants migrated towards Spain where they once again found themselves with illegal status. This type of chaotic imbalance in the EU’s system should be avoided by the creation of a common immigration policy that restores order to the phenomenon of immigration.

That was the opinion of Portuguese lawyer Antonio Vitorino, former European commissioner for justice and home affairs. Speaking in San Sebastian in June 2008, his comments were made during a series of summer courses on ‘the role of Europe in the world’. He defended the need for the controversial EU directive on the return of illegal immigrations, for ‘two fundamental reasons.’ On the one hand, he agrees with the objective of creating a ‘common platform for policies concerning the return of illegal immigrants.’ On the other hand, he considers that within migration policy, ‘return is one of the weakest points of its practical implementation by member states.’

‘Policy of shame’

Opposing the opinions held by the ex-commissioner and others, there is a large group that is critical of the new European directive passed in the European parliament in June. With this in mind, Diego López Garrido, Spanish secretary of state for the EU, emphasised that Spanish policy ‘is not going to change’ because the government defends immigration as a ‘positive and enriching phenomenon for our society,’ and one which should therefore be ‘legal’.

In the same country, the Basque government points out that the directive ‘allows measures of isolation that lack any judicial control and fail to guarantee the rights of anyone deprived of freedom have to legal, consular or medical assistance.’

Following its definitive referendum of July 2008 and with a timescale of up to two years for each member country to adapt to its respective legislation, this directive will allow the administrative detention of immigrants who do not have documents. This is allowed for in article 14, paragraph 2, which proposes that ‘decisions of temporary detention will be taken by the judicial authorities, but in urgent cases may be taken by administrative authorities.’

Following its definitive referendum of July 2008 and with a timescale of up to two years for each member country to adapt to its respective legislation, this directive will allow the administrative detention of immigrants who do not have documents. This is allowed for in article 14, paragraph 2, which proposes that ‘decisions of temporary detention will be taken by the judicial authorities, but in urgent cases may be taken by administrative authorities.’

One of the most problematic elements of this directive is the treatment of certain groups of the most disadvantaged immigrants, such as the young, the ill and those whose lives are threatened if they return to their country. Unaccompanied under-18s could be repatriated, even to countries where they have no guardian or family, calling into question the ‘best interests of the minor’ as taken into account by the international convention on the rights of the child in 1989.

America reacts strongly, Europe seeks compensatory measures

Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa, who christened the directive a ‘policy of shame’, declared that ‘it violates the right to free circulation and will make criminals out of those affected. ‘What would have happened if Latin America had adopted this directive with the Spaniards who were exiled from their country?’ In order to calm these tensions, the Spanish government has brought forward a bill that will allow legal immigrants residing in Spain for longer than five years to vote in the municipal elections.

Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa, who christened the directive a ‘policy of shame’, declared that ‘it violates the right to free circulation and will make criminals out of those affected. ‘What would have happened if Latin America had adopted this directive with the Spaniards who were exiled from their country?’ In order to calm these tensions, the Spanish government has brought forward a bill that will allow legal immigrants residing in Spain for longer than five years to vote in the municipal elections.

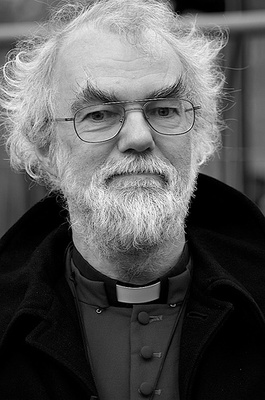

Other EU countries also anticipate measures designed to compensate for the situation. In the United Kingdom, the highest-ranking judge in England and Wales, Lord Philips, defended the idea that certain principles of Islamic (or sharia) law could play a role in the British legal system. Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury and head of the church of England, backed this initiative by stating that the introduction of certain aspects of sharia (or Koranic) law in this country ‘seems an inevitable’ part of promoting social cohesion.

Other EU countries also anticipate measures designed to compensate for the situation. In the United Kingdom, the highest-ranking judge in England and Wales, Lord Philips, defended the idea that certain principles of Islamic (or sharia) law could play a role in the British legal system. Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury and head of the church of England, backed this initiative by stating that the introduction of certain aspects of sharia (or Koranic) law in this country ‘seems an inevitable’ part of promoting social cohesion.

Translated from Nueva directiva migratoria de la UE: “política de la vergüenza”