Neopaganism: A Two-faced Belief?

Published on

Translation by:

Gabriel ButtigiegFrom Romania to Greece, neopaganism tries to raise itself to the ranks of the dominant religions. While these beliefs draw in young Europeans in search of an alternative spirituality, they also feed a nationalistic ideology. Have the Pagan gods made their return to Europe?

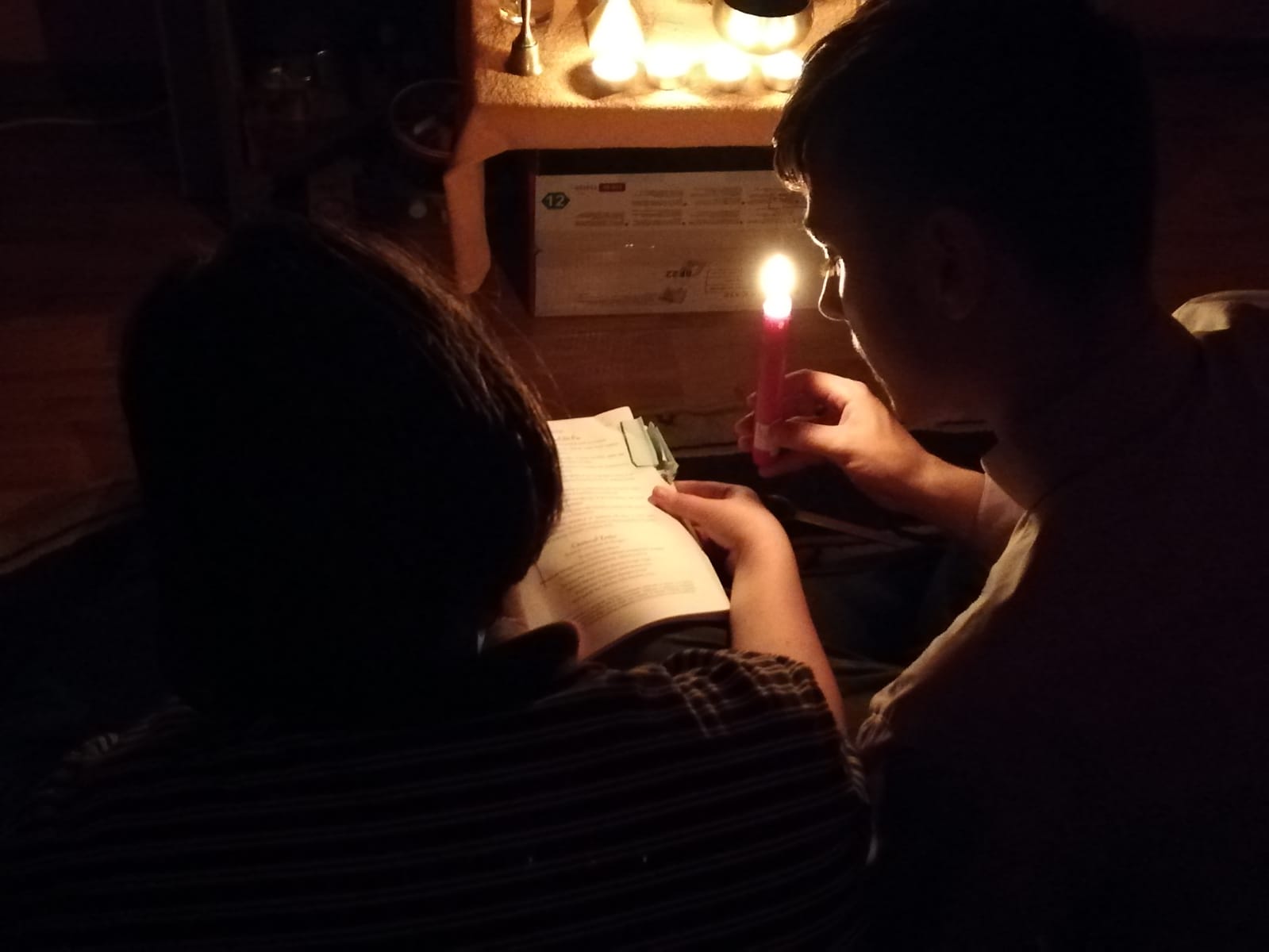

The chamber is plunged into darkness, the air is heavy with incense. Cosmin lights the green candle, the representation of man and nature, then the red, which represents birth and femininity. Cosmin puts the candles on the altar - an empty printer covered with a red cloth. A disparate collection of objects and symbols can already be found here: two little cups - one empty, the other half full of salt - a crystal pyramid, a Tibetan chanting bowl, a pendant representing Baphomet and, among the candles, a bust of a Pharaoh. With his prayer book in hand and the "Relaxing Wiccan Chants and Songs" playlist playing on Youtube, Cosmin is ready for his ritual.

"It's just a little ceremony, like evening prayer, so it's not very impressive," he says, as an excuse. With a candle in hand, Cosmin then turns towards the West, and begins his invocation. The scene unfolds in Baia Mare,Romania, an old industrial city at the foot of the Maramures a small chain of mountains in the north of the country known for its traditional festivals and wooden churches. It's just these old traditions and beliefs that interest Cosmin, president of the Neopagan Association of Romania, Ropaganism.

"You can take the practice of another religion that you find interesting and integrate it to your own prayers."

Neopaganism, that is, the resurgence of ancient beliefs and polytheistic religions present in Europe before the arrival of Christianity, is gaining more and more adepts on the Old Continent. If the majority of the most well-known and active neopagan groups are in Scandinavian countries, the inhabitants of the Balkans and Eastern Europe are also increasingly drawn by this new way of understandin spirituality thought the "return to traditions". László-Attila Hubbes explains in the book that he co-wrote, Modern Pagan Faith in Central Europe, that "neopagan religions are based on archaic doctrines, but ones which are updated to fit with modern needs." The new practitioners therefore do not hesitate to tint their ancient beliefs with concepts such as ecology, feminism, or even, in Cosmin's case, a true tolerance for homosexuality.

The new guard

Dressed in a grey priest's shirt with a Roman collar, sleeves carefully buttoned to the wrists, around his neck Cosmin wears a badge proudly proclaiming his membership in Ropaganism, of which he is both the founder and president. At only 19 years old, he tells his story well beyond his years. Raised as a Christian, he very quickly drifted away after he found out he was gay. At school, he found himself confronted with uninhibited religion-based homophobia. "I didn't recognise myself in any of these models. I did nobody any wrong but because I was gay, I should go to hell? It's not something I was able to accept," he confesses today. Nevertheless, he felt the need for spirituality, and so he turned to the internet to answer his questions. Through his research, he discovered Kemetism, a mix between Egyptian mythology, the famous Book of the Dead, and a certain type of magic. For him, it was a veritable revelation.

Cosmin, who feels "spiritually connected" to the Egyptian pantheon, points out the lack of strict dogma as a strong argument. "You can take the practice of another religion that you find interesting and integrate into your own prayers. As there isn't really a model, you can do what you want"

In 2018, he founded Ropaganism, an association which has gathered almost two thousand people in Romania. According to a study led by his association and based on data gathered by the National Statistics Institute, they could be almost 200,000 neopagans in the country. Cosmin receives the faithful in his spare room, the official headquarters of the association. On the walls are "protection spells," like prayers, and blessings hung up with scotch tape, side by side with a curtain bearing the association's logo. In his office, Cosmin has the Romanian flag to accompany a rainbow flag. A temporary installation, he says jokingly, while waiting for the association to finish the construction of its first temple in Brasov, the country's second largest city.

In the case of Ropaganism, the internet plays a major role in the recruitment of younger members, although proselytism is not " an activity that we practice," Cosmin explains. Numerous Facebook groups and other sites dedicated to sharing these cults are very easily accessed, to the point that, according to László, "neopaganism is probably the most marginal religion with quickest growth."

If believers can just "pass for weird people" as Cosmin summarises, in the neopagan sphere, neo-nazis equally gravitate towards it, including the Norwegian Varg Vikernes, who was arrested in 2013 for suspicion of terrorist projects.

The nationalist temptation

In part, it's this modern approach with a strong online presence which draws more people toward neopaganism. The Russian ethnologist Victor Schnirelmann estimates that the popularity of ancient beliefs is linked to the sentiment of being a part of their superiority culture. This starts to explain that neopaganism very often accompanied with exacerbated nationalism. In his study, László-Attlita Hubbes affirms this: "In analysing the Romanian neopagan groups, we see that all these extreme political parties were very present on the neopagan exchange platforms. The young are particularly exposed to their discourse and their political radicalisation." Coupled with the popularity of support online groups, this combination is potentially dangerous.

The most virulent and known of all these right-wing neopagan organisations is the Gebeleizis Society, founded in 2003 by Romanians Andrei Molnar and his brother Vasile. The association is known by its site which, in the midst of pamphlets on the superiority of Zamolxianism (the religion of Dacians and Thracians, two ancient peoples on the territory of present day Romania between 100 BCE and the first century CE, ndlr), relayed Arian propaganda, antisemitic messages and SS songs and symbols. They have also published texts calling for the rights of the Romani to be revoked. Dissolved in 2004, the association has nevertheless left a trail behind it, notably through online messages.

See also: Rodnovery in Poland: Don't call us Pagans

Cosmin assures us that he refuses to be affiliated with the Gebeleizis Society and that he does not at all share the same point of view on religion, although nationalist sentiments are often reflected in his discourse. "We want to promote our ancient roots, those of Thracians and Dacians. It's our real history, but the Church wants us to believe the opposite." The lies of Christianity and the supposed grandeur of the Dacians and Thracians are themes and images often taken up by small extreme right-wing groups. Zalmonixianistes make up approximately half of the members of his association, Cosmin estimates. Nevertheless, he assures us that he refused former members of Gebeleizis.

In the flames

In addition to ceremonies, Cosmin meditates between two to three times per week. "You must stay completely still in front of a mirror, with the lights out, with just candles and incense. You must go into a trance and look into the flames at the bottom of the mirror. And in that moment, our past lives appear in front of us", he says. Thank to this technique, he has even been able to see his own past and discover that he was the reincarnation of Alexander the Great and Ramses IV, among others.

"We want to be recognised as a real religion, but for the moment, the state doesn't listen to us at all."

Mona has not had the chance to contemplate her past lives. She is the vice president of Ropaganism, in charge of the region of Maramures. Today, she goes to Baia Mare to sign papers, in hope that her association is recognised. Unlike Cosmin, she is not a Kemetist. Mona identifies as a Wicca sorceress. Stemming from a mix of several beliefs and sources, including shamanism, druidism and certain Scandinavian mythologies, Wicca is a modern form of sorcery which draws in most part from the forces of nature. Now 34 years old, Mona converted in 2008 after searching how to do spells on the internet. Since then, she is a fervent practitioner. "It's something that has changed my life, my view of things. To be a Wicca sorceress is, first of all, to search for the balance between the good and the bad; that gives me the strength to try and have a positive impact on people." More than the magic that could be imagined, Mona interprets the fact of being a Wiccan sorceress rather like spiritual empowerment. The spells are closer to prayers than real curses, she explains.

To think big

Ropaganism aims to regroup all neopagans in Romania and help develop their spirituality. "It's very hard in Romania to totally assume our beliefs. The Church still has a lot of influence and, in our circle, that can be disapproved of." Cosmin recalls that his family beat him with a wooden cross when he announced that he was a neopagan. Today, he hardly has any contact with them.

But Cosmin also has more political ambitions. "We want to be recognised as a real religion, but for the moment, the Church is not listening to us. They say that Satanism cannot be official accepted. It's ridiculous because the freedom of religion is guaranteed by the Romanian constitution and not everyone is a Satanist in the association." His voice is full of anger, his eyebrows furrowed. "I just want to build a better world, but the authorities pretend they don't hear me." Last year, he sent numerous messages to different Romanian deputies in order to have a law passed that recognises their organisation. It hasn't received any response, but since then, he believes that he has been recorded by the secret services. "When I'm on the telephone, I often hear echoes. It's the sign that they're listening to me. That makes me very nervous, but it's my mission. I will continue to the end."

Other members of his association help him to reach his objective. Notably, the branch in Brasov, which has in the last few months obtained permission to build the first temple in the country. For the moment, it's only a vague terrain, but Cosmin and the other members of the office have high hopes.

Cosmin and Mona's ambitions for Ropaganism are not limited to the national level. The association already counts less than sixteen offices abroad welcoming Romanian neopagans living in France or in Germany. They still haven't had much success, Cosmin admits, but "they're only a the first step." For the moment, their international strategy is centred on cooperation with other neopagan organisations in neighbouring countries, where they are growing in number. In Hungary, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Slovenia or even in Greece, these organisations enjoy a greater importance, notably thanks to the ECER (European Congress of Ethnic Religion), that fights for the recognition of these religion. Ropaganism has still not been made part of it, but Cosmin is in contact in the hope of still further increasing is influence and of "federating all the neopagans of Europe".

On Olympus

In Greece, they're not called neopagans, but Hellenists. Installed in an apartment on the third floor of a tower block in the heart of Athens, their temple smells of myrrh, a mix of honey and spices. In the strangling heat of the Greek summer, the temple is fresh, and protected by the statues of the gods. No sign indicates its presence from the outside, although the location has recently been officially recognised as a place of worship.

"We have simply been very discreet for a long time, but our gods never died."

Ellena, the 45 year old High Priestess, is in charge of visits to the temple. Red drapes cover the walls and an imposing altar takes centre stage in the middle of the room. It is covered with sculptures, censers and even a ceremonial knife. The 12 main gods of the Greek pantheon are represented. Zeus and his throne at the centre of the room alongside his wife Héra, and Athena, the protective goddess of the city.

Hellenists don't consider themselves neopagans, since their religion has never completely disappeared. "We have simply been very discreet for a very long time, but our Gods never died," Ellena explains. The resurgence of Hellenism has been aided by the creation of their association, the YSEE (the supreme counsel of Hellenists in Greece) in 1997. Since then, their numbers have continued to grow, so much that after years of administrative processes with the Greek authorities, Hellenism was officially recognised in 2017. The cult is now considered a "real" religion, and celebrates marriages (over since 2017) and baptisms. In a country where orthodox religion is still very present, the announcement came out of the blue. Since then, membership has grown by 40%, Ellena says.

The young woman has considered herself a Hellenist since she was 18 years old. "It just seemed logical to me," she says today. "It's the religion of our ancestors, they are our traditions. For me, it explains the world far better than Christianity. The gods are more human, for example, they're jealous, and together they form a whole." Aphrodite represents universal love, Hestia the hearth, Hera the maternal figure. Ellena has been a member of the association since its creation, before becoming the High Priestess in 2014. She met her husband there, Costas, and here today with their daughter.

Between 100 and 200 people attend their monthly ceremonies, the most important of which are organised during solstices. Wearing an olive branch diadem, Ellena wears a white toga set with a red sash on these occasions. In the middle of the smoke of the burning myrrh, she sings hymns dedicated to the divinities. Oliver oil, flowers, honey, wine and bread make part of the offerings.

In addition to ceremonies, the YSEE also organise philosophical meetings, where different speakers explain the mythology and engage in theological debates. For Costas, this is different to other religions, "which demand blind obedience to certain principles. You learn more about the world and people with Hellenism."

A subversive heritage

Just like Kemetism, Hellenism is echoed in certain political parties. During the Greek economic crisis, the ultra-nationalist, far-right party Golden Dawn emerged. Described by its opponents as neo-Nazis, it isn't overtly Hellenist, but it draws heavily from its imagery. For example, it uses the crown of olives in its official logo and often makes reference to the grandeur of the ancient Greek civilisation within its discourse. The YSEE fiercely defends itself from any such affiliation with Golden Dawn. During an interview from 2018 on The Outline, the founder of the YSEE, Vlassis, was categorical: "There is no place for totalitarianism here. Fascist ideology is completely incompatible with ours." Ellena intends to enforce this vision.

But not all Hellenist groups are so categorical. This is what the neopaganism news blog supports - The Wild Hunt Panagiotis Marinis, founder of the Hellenist association Elliniki Etairia Arxaiofilon, following declarations in favour of Golden Dawn. Alexandros Kalozoides, a Greek researcher who is interested in the link between paganism and extremist political parties in Greece, goes even further: "The YSEE completely disavows Golden Dawn. But their adherents can be recognised in their discourse." An esoteric Greek magazine Esotérique, also points a finger to passages of Golden Dawn discourse which explicitly make reference to the Iliad, the mythical epic of the Trojan War. "It's exactly what happened with German Nazism, which tried to link the modern period with a past grandeur, the ultimate aim being to underline a certain cultural and racial superiority" Alexandros Kalozoides concludes.

See also: Chypre : twelve gods and a man

In the temple of the YSEE, they aren't worried about politics. Ellena prepares the next ceremony for the full moon, which will be given in honour of Hera, the mother of gods. Now that the Greek State recognises Hellenism, "it is time to try and change states of mind," says Sophia, another member present in the temple. "Certain members of my family still feel my religion suspect and think it's bizarre," she explains. "I often remember remarks at school, but now things are better, my friends and my professors at university are open-minded."

The temple doors closes. Ellena says goodbye by making a final blessing: "May the gods always shine on you."

This trip was made possible thank to a partnership with the European agency Interrail

Cover photo: © Grégoire Dao

See also: Partez en interrail journalistique avec Cafébabel

Translated from Néo-paganisme : des croyances aux deux visages ?