Melancholy in Berlin: views of three foreign writer residents

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)Very loosely, a 19-year-old Klaus Mann saw 1920s Berlin as 'seductive, gray, scabby, peeling, yet vibrant vitality, nervous, shimmering, phosphorescent, animated, full of tensions and promises.' Italian, Croatian and French writers Gianluca Falanga, Maksim Cristan and Maia Mazaurette give us their noughties take

On a cool morning in late May, the S-Bahn line number 25 leads me to Lankwitz where Gianluca Falanga is awaiting me for a chat. The writer, 33, has spent the last eight years in Berlin. 'I landed in Berlin during a phase in my life where I wanted to leave,' he says, making coffee. 'At the time, in 2002, it was a city in perpetual transformation. I identified with this metamorphosis.'

The Italian writer on Berlin

Gianluca, 32, has worked as a bookseller for several years, where he is a careful observer. 'Berlin is a city with a certain sympathy for an expatriate like myself. Indeed it is said that a 'real Berliner is not from Berlin'. The Salerno-born writer, who publishes mostly in German, considers Berlin unique for its provincial dimension. 'I find the city to be very big but equally unpopulated. It makes it feel a bit like a big village.' However, Gianluca's love for Berlin is matched by his disenchantment with it. 'Sometimes I give Italian lessons in a popular neighbourhood. It's an important experience to discover corners of the city that a mystical-intellectual microcosm doesn't know aboyt, and where the economic crisis is wreaking havoc. It's where we understand that this myth is just a myth, that Berlin is not such a small city and that there are very important economic and social problems.'

Gianluca, 32, has worked as a bookseller for several years, where he is a careful observer. 'Berlin is a city with a certain sympathy for an expatriate like myself. Indeed it is said that a 'real Berliner is not from Berlin'. The Salerno-born writer, who publishes mostly in German, considers Berlin unique for its provincial dimension. 'I find the city to be very big but equally unpopulated. It makes it feel a bit like a big village.' However, Gianluca's love for Berlin is matched by his disenchantment with it. 'Sometimes I give Italian lessons in a popular neighbourhood. It's an important experience to discover corners of the city that a mystical-intellectual microcosm doesn't know aboyt, and where the economic crisis is wreaking havoc. It's where we understand that this myth is just a myth, that Berlin is not such a small city and that there are very important economic and social problems.'

Gianluca believes that the human situations in Berlin are very formative and represent a constant source of inspiration for writing about a city in crisis. 'The crisis is being felt here. The economic trend is negative and the labour market is in a very difficult situation,' he says, with a melancholy air of realism. 'I'm changing my relationship with the city. Before, I would have said that Berlin, which is a city in motion, struck the right balance. Now I no longer believe that this is the case. It's turned out to be a normal city.' Berlin has arrived in the present but finds it difficult to enter it.

The Croatian writer on Balkan Berlin

I leave Lankwitz and head towards Schöneweide, to a bit of an unfriendly area thanks to its post-industrial charm. Maksim Cristan, a forty-three year old Croatian writer, appears at the window of an old factory building, motioning me to come up. His eyes are red from time spent in front of the computer screen. 'I'm so busy with my work that I don't sleep,' he smiles. 'That's how thinkers live.' Cristan speaks in excellent Italian as he exclaims: 'People here have lost their heads.' Maksim gesticulates eccentrically, his actions reminding me of the Italian actor Roberto Begnini, a kind of restless wandering mistrel. 'This city has some problems: it is now returning to neo-liberal normalcy. In this historical period [post-Berlin wall], there have been no jobs.' Maksim has lived in Berlin since October 2008 but he already seems to be disillusioned and realistic. 'The first time you get here is magnificent, everything is free, everything is beautiful. But if we dig a little more, it's not so. When I arrived I thought, finally something real. But freedom only exists to a certain extent. Suddenly my search ended there, because everything that I explored here was false.

I leave Lankwitz and head towards Schöneweide, to a bit of an unfriendly area thanks to its post-industrial charm. Maksim Cristan, a forty-three year old Croatian writer, appears at the window of an old factory building, motioning me to come up. His eyes are red from time spent in front of the computer screen. 'I'm so busy with my work that I don't sleep,' he smiles. 'That's how thinkers live.' Cristan speaks in excellent Italian as he exclaims: 'People here have lost their heads.' Maksim gesticulates eccentrically, his actions reminding me of the Italian actor Roberto Begnini, a kind of restless wandering mistrel. 'This city has some problems: it is now returning to neo-liberal normalcy. In this historical period [post-Berlin wall], there have been no jobs.' Maksim has lived in Berlin since October 2008 but he already seems to be disillusioned and realistic. 'The first time you get here is magnificent, everything is free, everything is beautiful. But if we dig a little more, it's not so. When I arrived I thought, finally something real. But freedom only exists to a certain extent. Suddenly my search ended there, because everything that I explored here was false.

The Croatian thinker dislikes the mentality of the core Berliners. 'As long as you queue properly everything is fine, but the moment you go out of the box, you're taking risks. This is the punitive mentality that is rooted in a part of all Berliners. Once a bus driver even told me that I had to pronounce the words correctly. They try to teach you how to live! But leave me in peace!' he exclaims, laughing. He becomes serious again when I ask him how easy it is to earn a living. 'The most I've earned in two years here are the sixteen euros I made singing with a musician friend one day in the Turkish market.' Maksim sees a clear difference between Berlin and the rest of the Germany. 'Germany is doing well. On the other hand, Berlin is rather like an Alfa Romeo; you take the door handle and it breaks, you lean on a door and it falls off. Ma vaffanculo!' he laughs. He has no regrets though, and is positive about the German capital. 'If I had to choose to live in Berlin again, I wouldn't complain. But I don't choose to live here anymore,' he smiles, adjusting his hat – Maksim plans to move to Italy in autumn.

The Croatian thinker dislikes the mentality of the core Berliners. 'As long as you queue properly everything is fine, but the moment you go out of the box, you're taking risks. This is the punitive mentality that is rooted in a part of all Berliners. Once a bus driver even told me that I had to pronounce the words correctly. They try to teach you how to live! But leave me in peace!' he exclaims, laughing. He becomes serious again when I ask him how easy it is to earn a living. 'The most I've earned in two years here are the sixteen euros I made singing with a musician friend one day in the Turkish market.' Maksim sees a clear difference between Berlin and the rest of the Germany. 'Germany is doing well. On the other hand, Berlin is rather like an Alfa Romeo; you take the door handle and it breaks, you lean on a door and it falls off. Ma vaffanculo!' he laughs. He has no regrets though, and is positive about the German capital. 'If I had to choose to live in Berlin again, I wouldn't complain. But I don't choose to live here anymore,' he smiles, adjusting his hat – Maksim plans to move to Italy in autumn.

The French (female) writer on Berlin

Back on the S-Bahn, I'm now en route to the heart of Berlin. Maia Mazaurette lives in Torstraße, in the central district of Mitte. The 31-year-old Parisian writer and blogger moved to Berlin in July 2006 'because I had had enough of Paris and seeing the same people.' Maia is smiling, even if her day wasn't one of the best. She is more talkative than Maksim, though he talks a lot. Maia is in love with the city, especially of her neighborhood, which is full of small art galleries. 'Here I can work quietly, manage my time, write and then send everything to Paris without too much stress! The day that Berlin gets more expensive I'll go,' she smiles. 'That's another reason why I'm here.' Maia loves the fact that Berlin has a great freedom of spirit, but she acknowledges that not everything is wonderful. 'It's very hard to get into the German circles, because all my friends are foreigners. Germans don't share the same spontaneity.' Maia also points out how much poverty there is in the city. 'It's been years here that people can't find work,' she states resolutely. She also confirms that Berlin is different from Germany. 'There's lots more chaos in Berlin, which has a particular ethnic and social diversity that you can't find in the rest of Germany.' She even jokes about the appearance of the city. 'It's ugly,' she laughs, 'You never know what to show to your friends who are visiting to make them appreciate Berlin. Today Berlin is a bit trendy, but it remains a beautiful city for young people. Fancy a coffee?'

Back on the S-Bahn, I'm now en route to the heart of Berlin. Maia Mazaurette lives in Torstraße, in the central district of Mitte. The 31-year-old Parisian writer and blogger moved to Berlin in July 2006 'because I had had enough of Paris and seeing the same people.' Maia is smiling, even if her day wasn't one of the best. She is more talkative than Maksim, though he talks a lot. Maia is in love with the city, especially of her neighborhood, which is full of small art galleries. 'Here I can work quietly, manage my time, write and then send everything to Paris without too much stress! The day that Berlin gets more expensive I'll go,' she smiles. 'That's another reason why I'm here.' Maia loves the fact that Berlin has a great freedom of spirit, but she acknowledges that not everything is wonderful. 'It's very hard to get into the German circles, because all my friends are foreigners. Germans don't share the same spontaneity.' Maia also points out how much poverty there is in the city. 'It's been years here that people can't find work,' she states resolutely. She also confirms that Berlin is different from Germany. 'There's lots more chaos in Berlin, which has a particular ethnic and social diversity that you can't find in the rest of Germany.' She even jokes about the appearance of the city. 'It's ugly,' she laughs, 'You never know what to show to your friends who are visiting to make them appreciate Berlin. Today Berlin is a bit trendy, but it remains a beautiful city for young people. Fancy a coffee?'

One last cafe to ponder Berlin, an excessively mythologised city which is always fascinating, and where the crisis seems more of an endemic condition which will remain temporary. Of course, being paid in Paris to live in Berlin is not a bad idea. At the terminus of this short literary journey Klaus Mann's words come back to me. They are still valid. I have not found a recipe against the crisis, but I know for sure that I won't be looking for work in Berlin - at least, not yet.

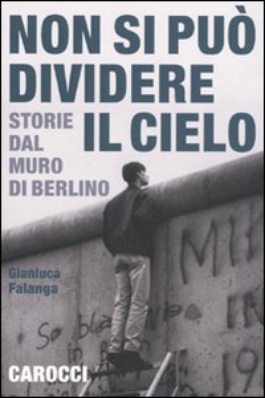

Gianluca Falanga, Non si può dividere il cielo. Storie dal Muro di Berlino, Carocci, Roma, 2009; Maksim Cristan, (fanculopensiero), Feltrinelli, Milano, 2007; Maïa Mazaurette, Osez... les rencontres sur Internet, Fluid Glamour, 2010

Images: ©David Tett/ davidtett.com and ©Chiara Dazi

Translated from Berlino, ritorno al presente: tre scrittori, tre storie, una città