Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders: France's extreme right stealthily advances

Published on

Translation by:

Marie JacksonWith far-right groups decrying the 'dictatorship of Europe', the continent appears to be witnessing a resurgence of nationalism. However, the popularity of these right-wing groups differs from one country to the next. In France, the National Front (FN) is becoming increasingly normalised in the eyes of the electorate.

Whether it's thanks to a new, truly moderate ideology, or simply a result of skewed media coverage, observers are asking whether other far-right parties in Europe could also use such tactics to garner support

Read Marine's interview with Julien Rochedy, leader of the National Front youth group.

At the end of January, FN leader Marine Le Pen appeared alongside leaders of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) at a student ball in Vienna. Some of the student fraternities present, like Olympia, are considered fascist organisations. Extreme-right groups across Europe thus appear to be joining forces to establish a European nationalist front, as further demonstrated by the creation of the European Alliance of National Movements, presided over by French far-right MEP Bruno Gollnisch. However, in order to gain influence at home, far-right parties try hard not to come across as such.

New champions of populism

In a post on the anti-Islamic news blog 'Bivouac-ID,' the author commented on the results of the legislative elections that took place in June 2010 in the Netherlands, where the freedom party (PVV) came third. 'The mindless hacks of the media would do well to remember that Geert Wilders' freedom party defends such values as democracy, the separation of the Church and State, gender equality, gay rights and the fight against anti-semitism. To claim that it is right-wing extremism to defend these values is to engage in full-blown semantic inversion.' Yet although the party defends manifestly republican values, vaunted by both the left and the right, and although it uses these values as the basis for its opposition to Islam, the PVV has also demonstrated considerable fervour for other key issues not listed by the author. Indeed, the website launched by Geert Wilders at the end of February provides indisputable proof of the party’s strong radical undercurrent; Wilders has called for Dutch citizens to use his site to lodge complaints against workers from Central and Eastern Europe, who are supposedly guilty of criminal offences, vandalism, prostitution and public intoxication.

Likewise, the current president of the Danish people's party (DF – Dansk Folkeparti) is a godsend for her party. Over the past decade, Pia Merete Kjærsgaard has helped the party evolve from small movement to key player on the Danish political scene. At the 2011 legislative elections, the DF won 12.3% of the votes, making it the third most powerful party in the country. This achievement is, in part, thanks to Kjaersgaard’s ability to revamp the party image. Her CV has been crucial to her success; having worked as an assistant manager in advertising and insurance, and then as a care-worker for the elderly, Kjærsgaard stood out against her peers drawn from top Danish universities.

What Le Pen and Kjaersgaard have in common is that they are both charismatic personalities. They protest the dictatorship of the media and the dominant neoliberal ideology, which - if we are to believe the controversial FN broadcast of April 2010 ('The Infiltrators') - are side effects of modern democracy. Furthermore, the leader of the FN is not afraid to play the victim. Indeed, Le Pen’s speech on February 12 in Strasbourg is just one example of how she seeks to forge a link between growing domestic insecurity and immigration, claiming: 'I will deliver a shock to left-wingers and the corporate upper class' and 'I don’t know if I will be dragged to court by the thought-police'. With an aim to mobilise working-class voters, Le Pen also perfectly understands how she must attack the outgoing presidential candidate: 'Nicolas [Sarkozy] is floating the referendum idea because, yes, the people are dangerous'. And, thus, the party blends into the political mainstream whilst remaining unchanged at its core.

Becoming part of the political establishment

On Monday, March 6, Marine Le Pen told a journalist who noted her connection to certain shady Austrian politicians at the Viennese student ball that 'in Austria, as in France, we must suffer people like you, those of the extreme left who, for years, have considered all those who disagree with them to be fascists and Nazis'. Le Pen underlined that the FPÖ is no different from the French socialist party. In other words, the FPÖ’s place within official political institutions demonstrates that it is a perfectly respectable party. Getting her wires crossed, the leader of the FN asserted that Martin Graf, member of the FPÖ, was also co-president of the Austrian national assembly and a regular member of the European council. After some fact-checking, it emerged that Graf is in fact a member of the council of Europe, a different institution entirely, but the message remains clear: the integration of a party into large political institutions and the popularity of said party among the electorate are to be taken as guarantees of its good faith.

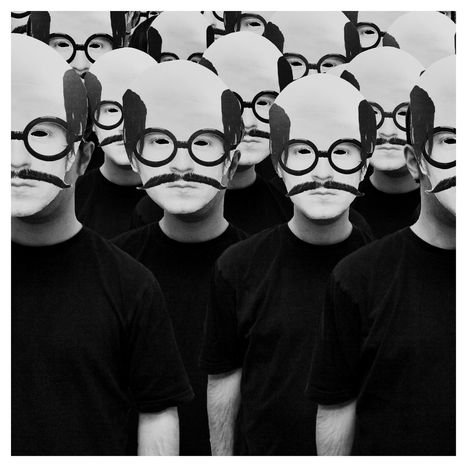

Although Marine Le Pen's arrival on the scene signalled the end of the traditional far-right in France, there are a number of far-right parties in Europe that have not engaged in the same game of pretence, including the national democratic party of Germany and the Italian northern league. Beyond these two examples, there are two branches of right-wing extremism muscling in on Europe: one, a collection of nostalgic fringe elements, and the other, a cluster of political parties armed with modern discourse. But the question remains: for which of these two groups is moderation just a mask, a makeover strategy to gain access to power?

Translated from Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders : l'extême-droite avance masquée