Lost in Europe: the long story of Dublin II, national laws and EU immigrants

Published on

Translation by:

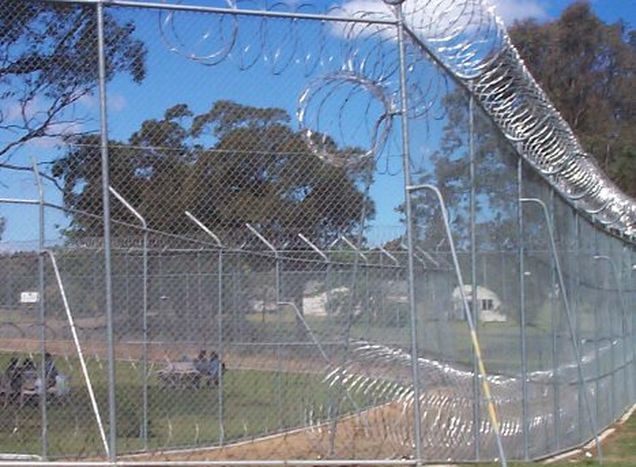

Helen SwainClandestine immigrants, regular immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees or repatriates; these many types of status all boil own to just one condition, that of immigrants faced with a legislative system that is constantly being redefined to be European. They come from so many different places, but in the majority of cases, the only destination awaiting them is temporary detention centres

How is the question being dealt with in Europe? European legislative framework is broad and complex, ranging from the European social paper to the European convention on social security. A milestone on the topic, however, is the Dublin II regulation, which was specifically prepared for a particular category of immigrant: asylum seekers, or, more precisely, anyone who with a 'well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion' (Geneva convention relating to the status of refugees, article 1). To request refugee status is, in fact, an inviolable human right, which states are obliged to provide rapidly and correctly.

Asylum shopping?

The Dublin II regulations refer particularly to asylum seekers, as they were created to prevent the so-called 'asylum shopping' phenomenon; in practice, the objective is to prevent immigrants from simply requesting refugee status in the European country offering the best social guarantees. To this purpose, therefore, it is provided that it is the first Schengen country in which the immigrant arrives and where his/her fingerprints are registered which must examine and receive any asylum requests.

The Dublin II regulations refer particularly to asylum seekers, as they were created to prevent the so-called 'asylum shopping' phenomenon; in practice, the objective is to prevent immigrants from simply requesting refugee status in the European country offering the best social guarantees. To this purpose, therefore, it is provided that it is the first Schengen country in which the immigrant arrives and where his/her fingerprints are registered which must examine and receive any asylum requests.

Thus, if an Iraqi arrives in Europe through Greece, s/he can only ask for asylum in Greece. So far, so good; however. ‘The problem is that not all the member states respect the parameters of protection determined by the European directives and the Geneva convention,' explains Julien Blanc, a veteran collaborator in French and Belgian detention centres. 'For example, in Greece, the recognition rate of asylum requests from Iraqi immigrants stands around 0%, compared to 76% in Sweden. In situations like that, it would be unjust to accuse immigrants of 'asylum shopping', given that in Greece they are denied rights that they can obtain in Sweden. The problem, in technical terms, is the absence of harmonisation among the Schengen countries of the rate of refugee status acknowledgement and of bad practice by some member states. NGOs have denounced the Dublin II system because it does not take into account different member states’ practices of acknowledging refugee status.’ Moreover, the Dublin II system unloads most of the burden of receiving refugees onto the countries in the south and east of the European Union in which, for evident geographical reasons, the majority of demands are registered.

Temporary detention centres on the verge of collapse

'Asylum cannot be submitted to quotas or restrictions. It is an international obligation that pertains to any state that has ratified the Geneva convention,' adds Pierre Henry, director general of France terre d’asile, one of the most important French associations to work with refugees and stateless people. One only has to glance at the situation in the temporary detention centres to grasp the gravity of the situation: Lampedusa is ready to collapse; in Greece there are no more detention centres available and asylum seekers have to sleep in overcrowded hotel rooms or in the street; for Chechens in Slovakia, the situation is similar to that in Greece; in Belgium, conditions are better but centres are equally overcrowded and there are not enough workers.

'Asylum cannot be submitted to quotas or restrictions. It is an international obligation that pertains to any state that has ratified the Geneva convention,' adds Pierre Henry, director general of France terre d’asile, one of the most important French associations to work with refugees and stateless people. One only has to glance at the situation in the temporary detention centres to grasp the gravity of the situation: Lampedusa is ready to collapse; in Greece there are no more detention centres available and asylum seekers have to sleep in overcrowded hotel rooms or in the street; for Chechens in Slovakia, the situation is similar to that in Greece; in Belgium, conditions are better but centres are equally overcrowded and there are not enough workers.

We should not forget that the immigration phenomenon in Europe is a significant one; the percentage of international immigrants is increasing faster than the world population, of which it makes up 3%, or 200 million people, equivalent to the fifth biggest country in the world. 30 to 40 million of these people are in an illegal situation. Although only 20% of the requests for asylum are accepted, the European Union remains the first destination for asylum seekers, and it alone receives more than half the requests presented globally, which is about nine times more than in the US. Principal countries of origin range from nearby countries like Russia, Serbia and Turkey to countries with serious political problems like Afghanistan and Iran.

The EU remains the first destination for asylum seekers, receiving more than half the requests presented globally

To conclude with the words of Jean-François Mattei, the president of the French red cross, pronounced on the occasion of the seminar on migration held at the council of Europe on 19 and 20 February: ‘We must speak for those who no longer have a voice, we must reach out to those whom some people do not wish to see because they are 'illegals'. We must do everything to protect them in what makes our humanity: their human dignity.'

First published 20 April 2009 on eudebate2009.eu

Translated from Lost in Europe: la lunga storia di un immigrato nell’Ue, tra il Dublino II e le leggi nazionali