Life in a refugee camp: changing our preconceptions

Published on

Translation by:

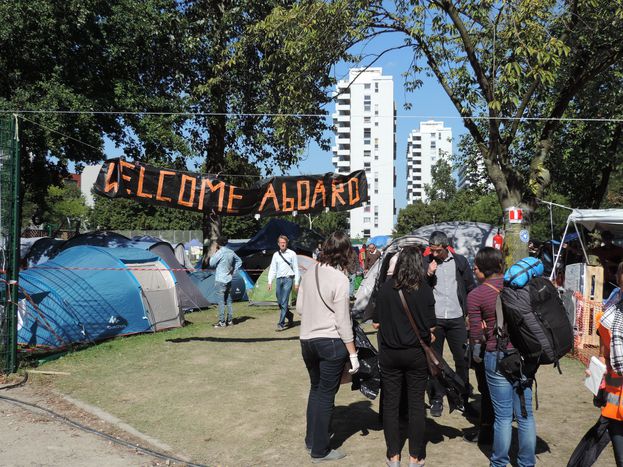

Danica JordenFor the inhabitants of the Parc Maximilien refugee camp in Brussels, day-to-day life continues. Located just across from the Immigration Office, the camp welcomes a steady stream of volunteers and donations as well as the massive influx of refugees. We take a look at how daily life here works.

When visiting the camp you get the impression that it is only able to function thanks to the generosity of local citizens. Using social networks, as well as word of mouth, volunteers have succeeded in creating a great sense of solidarity, fostering a comfortable and welcoming atmosphere to refugees often arriving after long and arduous journeys. Among the tents; clothing and food distribution points, medical assistance, and even schools for both children and adults. Every effort is being made to provide decent conditions for the refugees' arrival.

When I first step into Parc Maximilien, I am a little disoriented. As a Brussels native, even I feel lost in my own city sometimes. I can barely imagine how it must be for those arriving from overseas. The camp is impressively busy, the atmosphere buzzing with constant activity. There's always something for volunteers to do, whether it be cooking, sorting clothing donations, building furniture out of recycled objects, or seeing to camp sanitation. Not really knowing where to begin, I follow a couple of older citizens who are heading towards the school. As it turns out, I wouldn't have been able to find my way without them, the camp is far larger than I had imagined.

When we arrive at the "school" we find it overflowing with life. It's little more than a collection of tents, but children and volunteers alike are hard at work. A young girl colours a picture under the watchful eye of a volunteer. A group of women sort toys and stuffed animals from several large sacks of new donations. They take out bags of sweets, offering them to the delighted children: "We're mums too," they explain to me, "so we can put ourselves in the place of women arriving here with their children. It's a special feeling, we can't do anything to help them over there, so we try to do the most we can here, with what we have available."

A Spontaneous Initiative

Continuing my exploration I am intrigued by a group of women hanging sheets and tablecloths over a series of washing lines, erected amongst the trees. "We're setting up a women's space," one of them explains to me, "we're going to invite them to relax and talk." It's a lovely concept; the sheets create a private corner where women can take a quiet moment to catch their breath.

I ask if they belong to any association. "Not at all," answers Noémie, my first interviewee. "We met here yesterday. I had this idea in mind, then others joined in and we decided to give it a go to see if people liked it." That seems to be for the most part how things work here. Someone comes to the camp to give a donation and soon finds themselves lending a hand as a volunteer. Often people who intended to volunteer in a specific area end up working across more than one. Several volunteers say that they started this way. People go where the need is greatest.

I am intrigued by the idea of Noémie's initiative, but I remain a little doubtful of its potential to succeed. Earlier, I spoke with Isabelle, one of the volunteers taking care of a women's refuge. It's a place where women can go to pray, take a rest or change their babies. Volunteers are providing everything they need, but they haven't yet had much activity. "It has to start slowly," Isabelle explains. "but women are finally beginning to trust us. I think that's been the main problem in the beginning, there's a tendency for people to close themselves off inside their tents. What we've realised is that even though people may have come from more hostile places, they still face hostility here. It's a bit of a jungle for them. Slowly, when they start to recognise a few faces and get to know us better, they visit us more often. It's improving ever day."

Isabelle's testimony could give hope to the space built by Noémie and her new colleagues, if they take the time to gain refugees' trust. But it also makes me think. Her story runs counter to the narrative of refugees seeking to "take advantage" of the system. I discuss this with Amina, another volunteer. Taken aback by comments she reads on the internet, she attempts to set the record straight: "People must realise that those who come here are not only the very poor. They may have little upon arrival, but the majority have university degrees. At home, they have a job, a house... they didn't have a choice, they were forced to leave. Stop saying they are here to take advantage!"

Isabelle's testimony could give hope to the space built by Noémie and her new colleagues, if they take the time to gain refugees' trust. But it also makes me think. Her story runs counter to the narrative of refugees seeking to "take advantage" of the system. I discuss this with Amina, another volunteer. Taken aback by comments she reads on the internet, she attempts to set the record straight: "People must realise that those who come here are not only the very poor. They may have little upon arrival, but the majority have university degrees. At home, they have a job, a house... they didn't have a choice, they were forced to leave. Stop saying they are here to take advantage!"

Nabil, who came to the camp to give French lessons to adults, chimes in with a similar tale. He points out two of his students to me, a lawyer and an architect. The only thing they need besides permission to stay, is help to learn the language so they can find work.

_

Our local Brussels team is currently working on a dossier dedicated to Belgium's refugee camps. Solidarity, a strong effort and a big dollop of humanity... read all about it on the front page of the magazine soon.

Translated from Camp de réfugiés : dépasser les a priori