Illegal Immigration : Zero Tolerance Zero Rights

Published on

Translation by:

natasha hurley

natasha hurley

These days, the word ‘immigrant’ is synonymous with ‘criminal’ or ‘terrorist’, in contempt of basic human rights. Security doesn’t rhyme with liberty for immigrants.

At a time when the countries of the European Union are coming to terms with their vulnerability in the face of the terrorist threat, the issue of open borders and freedom of movement has cropped up once again, bringing with it a wave of demands and security measures. These measures are becoming increasingly legitimate in the eyes of the general public, a general public which is now openly fearful of foreigners. What does this turnaround in attitudes towards security imply in terms of individual liberties? Does it fulfil its objectives or does it herald the return of institutionalised xenophobia?

At a time when the countries of the European Union are coming to terms with their vulnerability in the face of the terrorist threat, the issue of open borders and freedom of movement has cropped up once again, bringing with it a wave of demands and security measures. These measures are becoming increasingly legitimate in the eyes of the general public, a general public which is now openly fearful of foreigners. What does this turnaround in attitudes towards security imply in terms of individual liberties? Does it fulfil its objectives or does it herald the return of institutionalised xenophobia?

Criminal Immigrants

At the root of the legislative crackdown on immigrants is the common perception that the immigrant is also a criminal. The construction of this “public enemy”, which is linked to growing economic and social precariousness in the West during the 1990s, has thrived on the speeches of politicians and the media, who were able to capitalise on economic problems and a general feeling of insecurity and social collapse. Foreigners are either seen as parasites fiddling the benefits system or as ‘Mafiosos’. Or, more recently, as terrorist bombers, a.k.a the worst enemy of the West.

This perception is exacerbated not only by the tendency to put legal immigrants, illegal immigrants, second-generation immigrants and asylum seekers in the same boat, but also by the existence of statistical proof which establishes a spurious link between crime and immigration (1).

A European combat

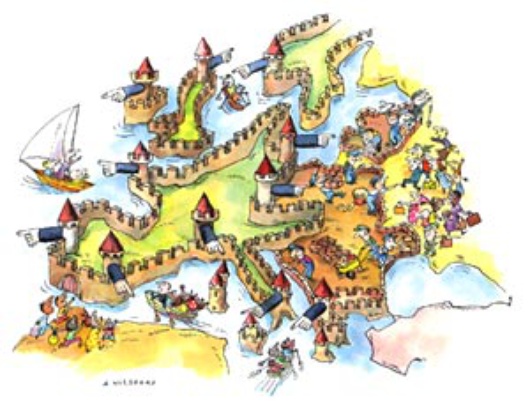

Legislation relating to foreigners carries the imprint of this blurring of boundaries. The fact that the combat against illegal immigration now takes place at the European level has only served to make the ‘danger’ more visible. European leaders, who perceive immigration to be a domestic security issue (2), have adopted instruments which together have led to the de facto construction of fortress Europe. Freedom of movement has forced governments to step up border controls, leading to a toughening up of visa policy, sanctions against people traffickers, co-operation with third countries, and increased identity checks. With enlargement, the accession states will become the guardians of the ‘wall’. They will only gain access to the Schengen area if they prove themselves worthy of it. The existing member states’ anxieties have migrated to this area, and they are now exhorting the new members to create buffer zones in order to repel undesirables coming from the East at their borders.

Ordinary Prisons

As a consequence of this preoccupation, heavy-handed tactics, such as deportation by charter or detention in camps or remand centres, appear legitimate. Their objective is to ensure that illegal aliens disappear from our sight. Behind the desire to shut them away is the notion of the immigrant as criminal or parasite.

There is a profusion of detention centres and camps in Europe (3). In most cases, they house both those who are awaiting examination of their request to enter -and whose itinerary will be subjected to a police investigation a few hours after their arrival in Europe, all the better to send them back to where they came from- and those who are already awaiting ejection, i.e. those who have been stopped at the border or who have received an exclusion order. In some countries (Germany, Britain), these functions are carried out by ordinary prisons and detention takes place under the same conditions as a prison sentence. Of course, the period of detention is laid down by law. But in practice, and with regard to living conditions, the reality of the situation is far removed from the procedural safeguards and humanitarian assistance which should be in place for foreigners (4). Deportation and detention usually take place in a legal grey area which is a sign of States’ inability to combat illegal immigration while upholding basic human rights.

Respect of basic human rights

Zero tolerance for illegal immigration in exchange for more welcoming and lenient measures for legal migrants: the EU wants to open up its borders for third country nationals who are coming to work or study.

The one thing missing from the equation is the protection of basic human rights. It gets a cursory mention by the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights: “Everyone has the right, on arrival at the border of a member state, to be treated with respect for his or her human dignity rather than automatically considered to be criminal or guilty of fraud (…) everyone whose right of entry is disputed must be given a hearing (…) The practice of refoulement ‘at the arrival gate’ thus becomes unacceptable”. What is more, the legal framework relating to the detention of immigrants is rather complex, and all the more so for foreigners, which makes it difficult for them to exercise their rights unassisted.

The security imperative rides roughshod over basic human rights in the name of efficiency in the drive against undesirables. These people are invariably suspected of the worst delinquent -or even terrorist- intentions. However, several studies and much research have endeavoured to deconstruct the putative link between immigration and crime: they show that not only does such an assumption constitute a breach of human rights, but it is also detrimental to the real fight against organised crime and terrorism. Unfortunately, the fear of the immigrant is the stock-in-trade of the media and certain political tendencies. Only an obvious failure of security policies will give those who denounce them and continue to fight for greater respect of established human rights a renewed opportunity to voice their concerns.

Translated from Immigration clandestine : zéro tolérance, zéro droit