Germans in Austria: Campus Doors are Open to Austria's Big Brother

Published on

Translation by:

Thomas McGuinnWhile hundreds of Southern Europeans pack their suitcases and move to Germany in search of a future, thousands of young Germans emigrate to their ‘little brother’ Austria every year to study in its universities. What does the Alpine country have to offer for thousands of German students who decide to cross the border every academic year to the small and always welcoming Austria?

If you ask any young Austrian whether they like their country, they’ll most likely say “yes”, but with a “but”. That’s what Austrians are like: They’ll always find something to improve, a “but” to add or some criticism to make. Even bearing in mind the general unemployment rate, which stands at 7.6%, and youth unemployment, which stands at 8.2% – figures which Southern Europeans can only dream of – when I asked various students in Vienna whether they liked their country and whether they were considering staying there to live, most of them told me that the country was “good”, but that they found it “boring”. “Nothing ever changes here…we’ve been living with this Grand Coalition for years and yeah, everything’s fine, but nothing ever happens”, Dunja told me reflectively; she’s studying plastic arts at The University of Applied Arts Vienna. If it is so boring, why do hundreds of students from all over the world come to study every year in the country of Mozart, Sisi and Sachertorte?

University for less than 20 euros

I arrived in the Austrian capital with a vague idea of what I was going to find and what I was not. And yes, I know that’s no good. They reckon you’ve got to see the world with an open mind, free from preconceived ideas and prejudices. However, it was more complicated in my case…I had spent a few months there a while back and I couldn’t get the image of an old-fashioned city out of my head. Hipsters would call it ‘vintage’ (well, if that sounds any better); it’s full of art and (haute?) culture which is elegant and stately, but not exactly youthful. And yet, the city of the Hapsburgs is home to the “oldest university in the German-speaking world," as was pointed out to me by the press office at The University of Vienna. This isn’t solely down to the Austrians, but also the large amount of international students who enrol in the degree courses there each year. Most are German. According to information supplied by the institution, out of the 90,000 students registered in the 2013-2014 winter semester, almost 10% (8,600) were from the neighbouring country. This phenomenon seems to have been happening for about ten years. This time, the number of those registered has risen by about 50% — from 62,602 in 2004 to 90,000 last year, an increase which has caused the collapse and overcrowding of university courses.

I arrived in the Austrian capital with a vague idea of what I was going to find and what I was not. And yes, I know that’s no good. They reckon you’ve got to see the world with an open mind, free from preconceived ideas and prejudices. However, it was more complicated in my case…I had spent a few months there a while back and I couldn’t get the image of an old-fashioned city out of my head. Hipsters would call it ‘vintage’ (well, if that sounds any better); it’s full of art and (haute?) culture which is elegant and stately, but not exactly youthful. And yet, the city of the Hapsburgs is home to the “oldest university in the German-speaking world," as was pointed out to me by the press office at The University of Vienna. This isn’t solely down to the Austrians, but also the large amount of international students who enrol in the degree courses there each year. Most are German. According to information supplied by the institution, out of the 90,000 students registered in the 2013-2014 winter semester, almost 10% (8,600) were from the neighbouring country. This phenomenon seems to have been happening for about ten years. This time, the number of those registered has risen by about 50% — from 62,602 in 2004 to 90,000 last year, an increase which has caused the collapse and overcrowding of university courses.

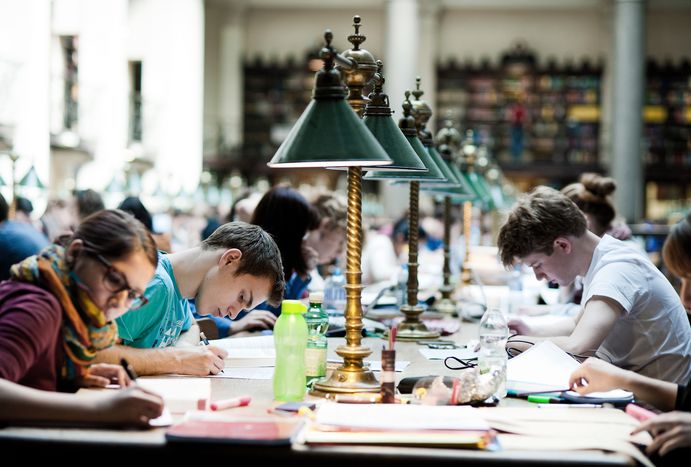

Rachel Miriam is among those 90,000. She’s from Berlin and is the daughter of a Spanish father and a German mother. When she finished college, Rachel was thinking about going to Barcelona, but settled halfway and moved to Vienna. “This city’s like a well: You enter and never leave,” joked the communications expert who’s been living in the “boring” city of Vienna for six years. “I studied at the FH, a slightly more expensive institution than The University of Vienna, but with visiting lecturers and smaller classes,” she explained. When she finished her degree in 2013, she considered going abroad to do a Master’s, but after seeing the fees in the rest of Europe, she decided to stay on in Austria. “My Spanish friend has paid 18,000 euros to do a two-year Master’s course, and I’m paying 18.50 euros per semester here,” she told me. That’s about a thousand times cheaper. Could this be the only reason they’re able to attract so many students to the imperial capital? She answered with an emphatic “No.” “Rent prices are actually more expensive here than in Berlin, but the thing is, it’s pretty much impossible to get into university there.” In Germany, getting into the university courses depends on the minimum grade-point average needed and the competition is fierce. By contrast, anyone in Austria who is able to pay the annual fee of 18.50 euros to the students’ union can enrol onto whatever course they like, with the exception of the five subjects in highest demand, which require you to take an exam before enrolling. “It’s crazy in my country. I came here to study psychology and I couldn’t even do it in the end, because I didn’t pass the exam, but it would’ve been almost impossible for me to study anything in Germany,” I was told by Hanna, Dunja’s classmate at The University of Applied Arts Vienna, who’s enrolled on The University of Vienna’s German Language course. “The courses certainly aren’t personal. I have to sit on the floor sometimes in the Master’s classes to take notes…But, everyone can study here and it’s good quality,” she added.

Rachel Miriam is among those 90,000. She’s from Berlin and is the daughter of a Spanish father and a German mother. When she finished college, Rachel was thinking about going to Barcelona, but settled halfway and moved to Vienna. “This city’s like a well: You enter and never leave,” joked the communications expert who’s been living in the “boring” city of Vienna for six years. “I studied at the FH, a slightly more expensive institution than The University of Vienna, but with visiting lecturers and smaller classes,” she explained. When she finished her degree in 2013, she considered going abroad to do a Master’s, but after seeing the fees in the rest of Europe, she decided to stay on in Austria. “My Spanish friend has paid 18,000 euros to do a two-year Master’s course, and I’m paying 18.50 euros per semester here,” she told me. That’s about a thousand times cheaper. Could this be the only reason they’re able to attract so many students to the imperial capital? She answered with an emphatic “No.” “Rent prices are actually more expensive here than in Berlin, but the thing is, it’s pretty much impossible to get into university there.” In Germany, getting into the university courses depends on the minimum grade-point average needed and the competition is fierce. By contrast, anyone in Austria who is able to pay the annual fee of 18.50 euros to the students’ union can enrol onto whatever course they like, with the exception of the five subjects in highest demand, which require you to take an exam before enrolling. “It’s crazy in my country. I came here to study psychology and I couldn’t even do it in the end, because I didn’t pass the exam, but it would’ve been almost impossible for me to study anything in Germany,” I was told by Hanna, Dunja’s classmate at The University of Applied Arts Vienna, who’s enrolled on The University of Vienna’s German Language course. “The courses certainly aren’t personal. I have to sit on the floor sometimes in the Master’s classes to take notes…But, everyone can study here and it’s good quality,” she added.

Overbooking on campus

But, what about the Austrians? Are they as old-fashioned as people make out? “I’ve not got any problems with them but I have noticed a certain amount of rejection from some people. When they hear my accent, they say things to me like ‘we’re not in Germany,' but maybe they’ve got a problem with being the ‘little brother,’” said Rachel. The little brother? “Yes, Austrians always have to get used to Germany, watch our television programmes, watch our news. And we don’t have to watch theirs, so lots of people are bitter.” It does not seem to be a wide-spread problem in any case, since Hanna assured me that most of her friends are from Austria. Furthermore, the target of the riots a few years ago, when the number of students began to skyrocket, were not against the people who had recently arrived in the country, but the Austrian government. When it started to introduce measures to reduce the amount of people studying there, students hit the streets to demand more economic investment and fewer restrictions, which is something that the Österreichische Hochschülerschaft (OH), or Austrian Students’ Union, is working on. I met the Union’s adviser, Daniel de la Cuesta, at the association’s head office which was deserted at that point in September when the academic year was not yet underway. As well as acting as mediators, the ÖH offers language assistance, legal advice, mental help and even financial support in the extreme case of a student not being able to pay the rent in exceptional circumstances. Daniel pointed out that, “There’s no doubt that the University is very much overbooked, but there’s a very flexible system in place which lets you choose the subjects you’d like to do and it is free of charge to European students.”

The flip side of this idyllic system is that one’s studies can go on for years. Daniel’s thoughts on this matter are that, “An Austrian might finish his degree at 25 years old after having to wait to enrol into certain subjects, but it’s better to do it that way and have experience under your belt than finishing at 22 without ever having step foot in a company, right?” It’s like that, because unlike stricter countries, students in Austria can undertake work experience from their very first course units. At this point in the conversation, Daniel must have seen the twinkle in my eyes, because it was impossible for me to compare all the advantages that he was listing with the rigid Spanish system where I received my education, with fixed four-year degrees and university fees which are sparking real controversy amongst the student body there. “Of course, there’s a limit to the amount of calls you get to pass all subjects. You’re given two semesters’ leeway and then if you don’t keep up your half of the bargain, you’re stripped of all support and start to pay for your credits. Moreover, if you resit a subject more than twice, you get expelled from the university and all doors are closed to you in Austria,” he explained. All in all, it doesn’t seem like a bad deal to me: A good offer must always bring with it the expectation of certain responsibilities.

No country for young people?

But what next? Some Austrians complain that the government is making a solid investment in its university education that benefits many foreigners who leave the country once they have finished their degree. “I like this city very much and I really was thinking about staying here to live, but I have been missing Düsseldorf and my parents a lot for a while now, so I guess I’ll go back home to Germany when I’m done," admits Hanna. Like her, Rachel is also thinking about leaving, because she thinks that Vienna “doesn’t have many opportunities” for her. “I want to go to Germany or Spain, or Switzerland, because not much goes on here, people end up working for either a bank or an insurance company. It’s a small country and there are no big companies, only two or three,” she complains.

But what next? Some Austrians complain that the government is making a solid investment in its university education that benefits many foreigners who leave the country once they have finished their degree. “I like this city very much and I really was thinking about staying here to live, but I have been missing Düsseldorf and my parents a lot for a while now, so I guess I’ll go back home to Germany when I’m done," admits Hanna. Like her, Rachel is also thinking about leaving, because she thinks that Vienna “doesn’t have many opportunities” for her. “I want to go to Germany or Spain, or Switzerland, because not much goes on here, people end up working for either a bank or an insurance company. It’s a small country and there are no big companies, only two or three,” she complains.

This seems to be the failed subject that has stayed with the city. Despite boasting enviable employment rates, fairly solid political stability and a quality of life which put it amongst the top cities on the planet, the elegant Vienna just does not appear to be winning over the new generations. But perhaps this is just a matter of time. I spoke to Austrians during my time here and all of them told me that the city has changed a lot over the last ten years. Alongside its majestic palaces and elaborate concert halls, its romantic parks and cafés, the Neubau located in the city centre is a hotspot for art galleries and second-hand shops, and MuseumsQuartier takes on new life after sundown, as hundreds of young people go there to drink Sturm and mulled wine. Time will tell, but perhaps these young people who are critical of the city today are not quite aware of the fact that they are the ones who are changing Vienna, they are the ones waking it up from its slumber.

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF OUR COLLECTION OF REPORTS ENTITLED “EU-TOPIA: TIME TO VOTE”, IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, THE FRENCH MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE EVENS FOUNDATION.

Translated from Alemanes en Austria: un campus con las puertas abiertas