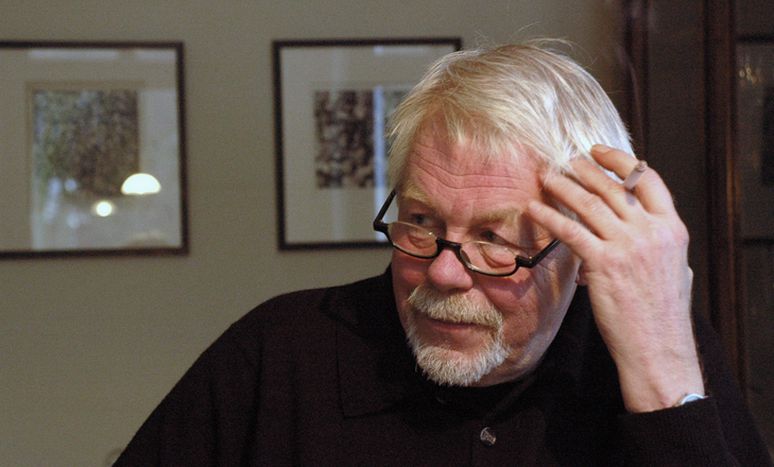

Gerhard Glück:'I live a middle-class life and make middle-class art'

Published on

Translation by:

Andrew Christie

Andrew Christie

Something’s not right in next door’s garden – at home with the award-winning German caricaturist, 65, who paints miniature scenes from across the Swiss border

The hedges in the front gardens are neatly clipped. The high fences dividing the houses are almost out of sight. The Audis and Volvos sit safely in the double garages. The shutters are pulled down at night – often automatically. Everything is well-ordered, with a view of the golf course fairways. Only one person stands out in this idyllic spot: caricaturist Gerhard Glück, probably Germany’s sharpest satirist of the middle-classes, who lives in the heart of middle-class Germany in a beautifully located art-nouveau villa on the hillside overlooking Kassel. Only here is he able to produce the art that has already earned him three German caricaturists’ prizes (2000, 2001 and 2005).

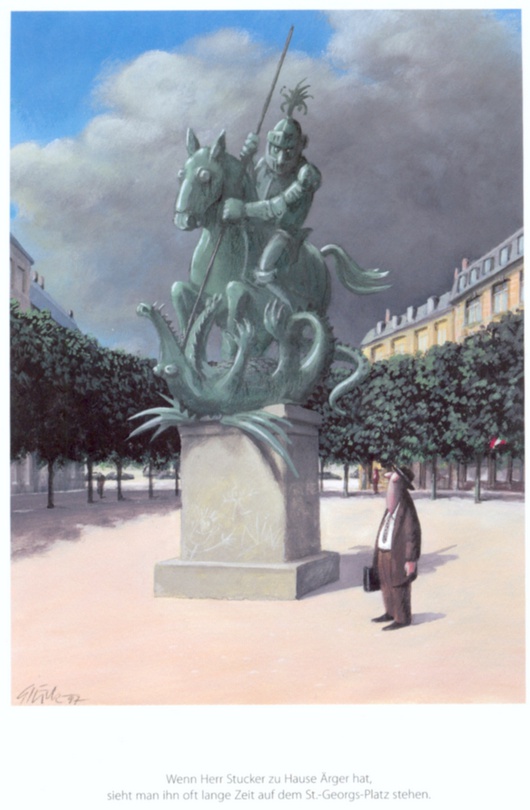

Unlike most of his colleagues, Glück does not quickly sketch political lampoons, but paints miniature scenes with acrylic and tempera. Chinless, sturdy average Europeans are captured in their little day-to-day dramas, with their petty-bourgeois ways. Like Mr Stucker, for instance. He is depicted as a small, grey man with a briefcase and hat, standing before a statue and gazing up at it in awe. On the plinth, a knight is in the process of heroically slaying a writhing dragon with his lance. The caption reads simply: When Mr Stucker has troubles at home, he can often be found passing long periods of time in St. George’s Square.

Unlike most of his colleagues, Glück does not quickly sketch political lampoons, but paints miniature scenes with acrylic and tempera. Chinless, sturdy average Europeans are captured in their little day-to-day dramas, with their petty-bourgeois ways. Like Mr Stucker, for instance. He is depicted as a small, grey man with a briefcase and hat, standing before a statue and gazing up at it in awe. On the plinth, a knight is in the process of heroically slaying a writhing dragon with his lance. The caption reads simply: When Mr Stucker has troubles at home, he can often be found passing long periods of time in St. George’s Square.

Before he became able to live off his comic artwork, Glück was a school art teacher. One day a friend suggested that he send his sketches off to some newspapers. He soon received a reply from the Süddeutsche Zeitung: 'Interested, would like more.' Eventually Glück gave up his teaching job and began to work purely as a caricaturist. For the last decade he has mainly worked for the magazine section of the Neue Zürche Zeitung, the NZZ Folio.

Glück’s law in Switzerland

Working from across the border is not all that straightforward, as Glück has to send original copies of his drawings to Zurich by express delivery – or even, when it is really urgent, via the intercity express train. His pictures are scanned in-house and the colours in the magazine adjusted to complement them. They are later returned to him. 'Sometimes in the past I’ve had to hand over the pictures at customs – a huge problem, if they don’t believe that they are my property.' Now, however, a sort of 'Glück’s law' has been established at the Swiss customs: the funny pictures have become well-known.

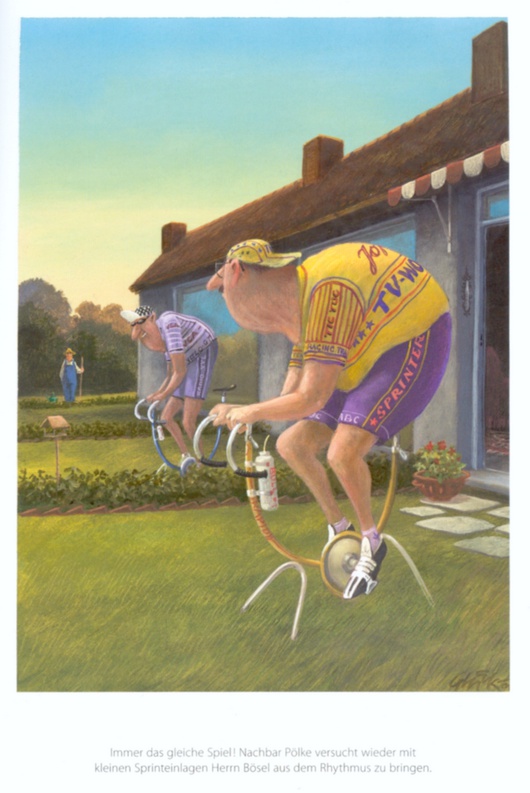

Glück is currently illustrating a collection of Joachim Ringelnatz’s poetry. His pencil sketch shows a street corner with three stumbling drunks. Over his wife’s cake, he explains how the light should fall and how he will change it completely before it is drawn properly. His explanation betrays a man of knowledge, ambition and meticulousness. As he introduces light to the picture with deft hand movements, the embers of his cigarette dangle dangerously, in the end falling neither on the paper nor the cake. Glück takes another long drag and mutters: 'What I draw is just silliness, scraps of entertainment.' He peers over the top of his glasses: 'But flippancy is my bread-and-butter. It would be ridiculous for me to try to tell you I’m a great artist. I live a middle-class life and make middle-class art.' For this 'middle-class art,' the 64-year-old has had numerous books published and exhibitions set up all over Europe. Really, when two competitive neighbours have a race on their exercise bikes and the punch-line is printed in French, right away they can only be one thing: bourgeois Frenchmen.

Glück is currently illustrating a collection of Joachim Ringelnatz’s poetry. His pencil sketch shows a street corner with three stumbling drunks. Over his wife’s cake, he explains how the light should fall and how he will change it completely before it is drawn properly. His explanation betrays a man of knowledge, ambition and meticulousness. As he introduces light to the picture with deft hand movements, the embers of his cigarette dangle dangerously, in the end falling neither on the paper nor the cake. Glück takes another long drag and mutters: 'What I draw is just silliness, scraps of entertainment.' He peers over the top of his glasses: 'But flippancy is my bread-and-butter. It would be ridiculous for me to try to tell you I’m a great artist. I live a middle-class life and make middle-class art.' For this 'middle-class art,' the 64-year-old has had numerous books published and exhibitions set up all over Europe. Really, when two competitive neighbours have a race on their exercise bikes and the punch-line is printed in French, right away they can only be one thing: bourgeois Frenchmen.

The key to Glück’s dry, European humour lies not only in the picture, but also in the two lines of text underneath. Ostensibly, they describe only what is visible, but Glück’s characteristic terseness and sense of absurdity lend the piece another dimension.

Shift

When Glück was working for the Süddeutsche Zeitung in the seventies, his style was different again: 'I didn’t want any text at all, as I was fascinated by the idea of pictures being expressed pantomime-style – in the tradition of great illustrators like Chaval and Bärbel Stangenberg, who were funny without words.' What he does now is essentially, in art-history terms, quite avant-garde: instead of presenting political arguments and overplaying the ugly side of life, his caricatures are first and foremost nice to look at. As he puts it himself, with a nod to the Biedermeier movement (19th century Germany furniture style) and one of its most prominent artists: 'Spitzweg-esque.' Read the text, however, and the charm becomes humorous and the message mischievous.

He finds inspiration for his characters in the papers, on TV and even in next door’s garden. For Glück, the essence of bourgeois society lies there: 'One resident, for example, threatened the whole neighbourhood with legal action. He took a ruler to measure the distance between our hedges!' Deep down, he is indebted to them; almost to the point of owing them royalties: 'My neighbour is one of those incredibly strong women. Once she was playing ball in the garden with a tiny dog. I immediately took out my sketchpad and named my drawing Endangered Creatures.' Glück laughs his cheeky little boy’s laugh and lights his next cigarette. For almost three decades he has drawn at home, where he not only smokes, but by his own admission drinks coffee by the bucketful. And drawing isn’t all he does at home. 'Right now,' he grins, disappearing from the dining room and returning with an acrylic-glass silhouette of a strange dog screwed onto a piece of square wood. 'I had fun at Christmas, messing about a bit with the fretsaw.' The 'cold dog', as Glück calls it, can be lit up from below with an LED, making the edges shimmer in blue light and transforming the dog into a caricature.

Glück does not just create tongue-in-cheek art for the public, but is also an avid hoarder, like Picasso, and crafts oddities for his family. (Glück modestly plays down this comparison.) 'I could also make acrylic-glass ‘cold dogs’ using politicians. And then market them for a fortune,' he says. However, you cannot imagine such low-down tactics from a man who even forgot about the cigarette in his mouth. Well might he be aware of his own bourgeois status – he smokes with the rebellious coolness of the young D'Artagnan in French cinema, Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Glück does not just create tongue-in-cheek art for the public, but is also an avid hoarder, like Picasso, and crafts oddities for his family. (Glück modestly plays down this comparison.) 'I could also make acrylic-glass ‘cold dogs’ using politicians. And then market them for a fortune,' he says. However, you cannot imagine such low-down tactics from a man who even forgot about the cigarette in his mouth. Well might he be aware of his own bourgeois status – he smokes with the rebellious coolness of the young D'Artagnan in French cinema, Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Translated from Die spitzwegigen Spießer des Gerhard Glück