François Ruffin: "We're not strong, so we have to be clever"

Published on

Translation by:

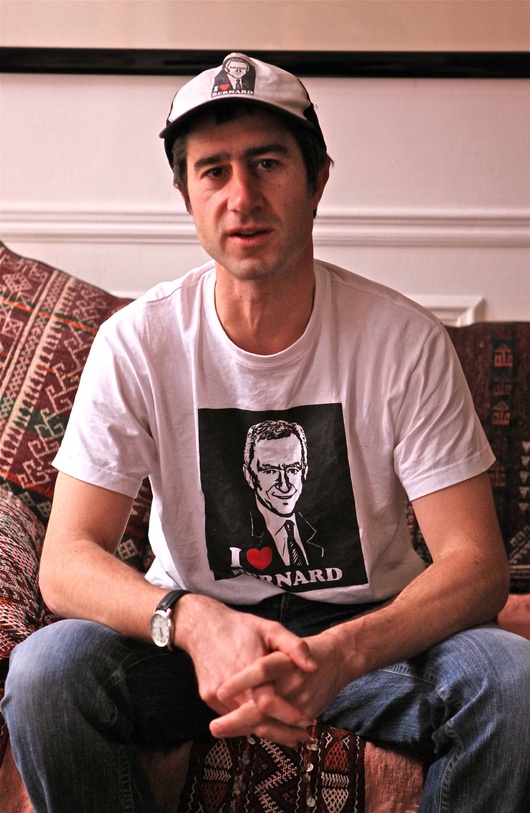

Arwen DeweyHis film Merci Patron! sparked Nuit Debout and the Loi Travail protests: two of the largest, but sadly short-lived, French social movements of the year. Now, six months after it all started, François Ruffin brings up Molière and Marivaux as he talks about the production of his film and its impact today as a symbol of the struggle.

cafébabel: Was the script for the film Merci Patron! written in advance, or did you create it as the actual events were happening?

François Ruffin: Fighting always means adapting to the terrain, and since we're not the strongest, we have to be the cleverest. The idea began with the Bernard Arnault [CEO of LVHM] t-shirt. I knew the Klurs [the family featured in the film], and Samaritaine, so I already had a few reference points. But really, there's something magical about this film: it’s all based on one meeting between the Klurs and the commissioner [the intermediary between the Klurs and Bernard Arnault]. The film was created live and on-screen. Its spectators become part of the action and end up committed to the fight.

cafébabel: Did you plan your moves out in advance?

François Ruffin: No, we had no way of knowing that Bernard Arnault would reply to the letter we sent him. But when he did respond, it created an infinite number of imaginative possibilities for the script. The whole thing started with a misunderstanding straight out of Marivaux or Molière, and from there everything else just fell together. The bond I established with the commissioner turned it into a film about espionage and counter-intelligence. We even managed to send a Trojan horse into LVHM to poison them.

cafébabel: We see in the film that Bernard Arnault's intermediary is afraid of your newspaper, Fakir. It almost seems like he's more afraid of Fakir than he is of other major media companies. Do you know why?

François Ruffin: The commissioner's exact words are "It's the vocal minority that gets things done." So yes, for him, Fakir is more of a threat than Le Monde, France Inter, Jean-Luc Mélenchon [former Minister of Vocational Education, ed.] or François Hollande. But I don't think it's Fakir itself that scares him. I think he couldn't care less about the newspaper. It’s Fakir's activism, its ability to stubbornly stick with a story, and its ability to bring people from different worlds together: the unions, activists, the press... I would put it this way: Minorities can do a lot if they can manage to reach others, the masses, the people. A train without any cars behind it isn't much use. The question is, how do you get the cars behind a vocal minority?

Trailer for Merci Patron!

cafébabel: How exactly do you go about reaching the masses and the people?

François Ruffin: The paper needs to come out of the shadows. We’re talking about activism, which has been the focus of Fakir for many years. We’ve gone from information to activism. We regularly have one, two, or three stories going on at once, symbolic cases that we argue about with our subscribers, who are also activists. I think that exposure is counterproductive these days. When you tell people, "There are companies relocating to Poland," they already know that. "Rich people are putting their money in tax havens," they know that too. Exposés just reinforce that feeling of helplessness. So instead, we have to reach people by showing them the possibility of change. We find one little example and show people that the problem can be solved. What happened to the Klurs has universal value. Bernard Arnault is the wealthiest man in France, but if we try, look what we can accomplish. The Klurs are a valuable example.

cafébabel: Is what happened to the Klurs something that can be duplicated?

François Ruffin: Not in the same way, no, we can't re-use the same tactics. The film is about the balance of power. How do you recreate a balance of power when you're David facing a behemoth of a Goliath? I believe in engaging people's emotions. There’s so much talk about how storytelling is a bad thing, but I think that's all wrong. Storytelling plays a role in people's lives, and it needs to be used in a progressive way. You can't get people to act without reaching them emotionally. When we tell the Klurs' story it's not abstract information anymore, it isn't 7 million people living in poverty. It becomes Jocelyne and Serge, and despite themselves they become the representatives of millions of people across the country. You have to bring the faces out of the crowd. There is more in their story than you'll find in all the speeches about job insecurity combined.

cafébabel: Since the film came out, have you noticed a change in the visibility of your newspaper and your activism?

François Ruffin: Yes, absolutely. But in the same way I ran a campaign to support the Klurs, I'm organizing a campaign to bring the film out of the shadows. This film can reach anyone. I’m convinced that it can bridge social barriers, and I've come up with a strategy to make that happen. There are several obstacles that need to be dealt with! But sometimes our enemies help us. When Bernard Arnault replied to our letter, for example, it created an opening.

cafébabel: What advice would you give to local and community newspapers and other alternative newspapers in this fairly precarious system? Is it absolutely necessary to combine activism and exposure? Are there other ways of going about it?

cafébabel: What advice would you give to local and community newspapers and other alternative newspapers in this fairly precarious system? Is it absolutely necessary to combine activism and exposure? Are there other ways of going about it?

François Ruffin: I've never really cared about the survival of Fakir as a newspaper. I’ve always been more interested in how Fakir can succeed in having a political effect. And on that count, we have to constantly question ourselves. I’d say that, economically speaking, as long as we only have to pay the printer, we manage. The projects that die don't die for economic reasons, but because the people working on them, writing them, don't see any reason to continue. The question is, how do we find reasons to keep doing what we're doing?

cafébabel: When we see things like what's happening with Caterpillar in Belgium, it brings to mind issues that you've been reporting on for years. What’s the future of the worker's struggle in Europe?

François Ruffin: Fakir was created when Yoplait's factory was offshored. We've been standing up for worker's rights ever since. The labour movement is the heart of Fakir, and that includes the decline of the already-struggling labouring class. People call me a workerist, but I don't really agree. I am in a certain sense, because labour and industry are an important part of Fakir, but at the same time "workerist" suggests that workers are the future of humanity, and that's not what I believe. I believe that the working class is suffering, and that it's being hit hard by globalization. I stand in solidarity with the working class because it's being hit so hard, but that doesn't mean that I believe our entire future depends on the workers, or at least, not only on them. Their fights can last for ages. Goodyear lasted seven years because of the determination of the unions and the workers. They bought themselves some time. But in the end, the factory was offshored. The strongest possible movement against Caterpillar/ Goodyear will ultimately fail if the macro-economy doesn't change. I’m on the side of protectionism. I question the free circulation of capital and merchandise, and as long as we don't have the will to regulate, we can't move forward.

cafébabel: After Merci Patron!, what's next?

François Ruffin: The next film is being written every day. Right now, we're looking at an Ecopla factory in Saint-Vincent-de-Mercuze. We're bugging Macron, the former Minister of Finance. We’re partnering with the unions too… but that probably won't make it into the next film.

___

This article was written by the editorial staff of cafébabel Brussels. All rights reserved.

Translated from François Ruffin : « Nous ne sommes pas les plus forts, il faut être plus rusés »