France’s European migrants disenfranchised

Published on

Translation by:

zoë brogden

zoë brogden

The majority of European migrants in France have no voice in the upcoming elections. They describe the nationalistic overtones of the presidentials as 'overwhelming'

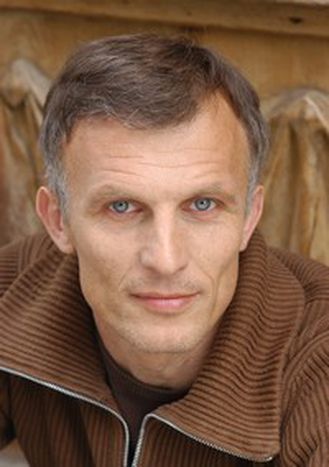

'I’ve paid 21 years of taxes but I can’t vote – it’s madness!' The rage in the voice of Richard Sammel, 46, is difficult to ignore. Despite living in France since the eighties and educating both of his daughters there, the fact he refuses to relinquish his German passport denies him at the ballot box. Sammel, born in Heidelberg, Germany, defines his job title as a 'European actor', always moving where the best offer was available. In essence, this meant six years in Italy, followed by a year in Spain and England. Today, his film roles take him throughout Europe.

His role this time is clearly as a spectator. Ségolène Royal, the Socialist hope, sets her stall out as 'La France Présidente', or 'the French President'. The former Interior Minister and Conservative Nicolas Sarkozy takes a tougher stance on immigration and security policies.

'Content–wise, it’s very flimsy,' complains Sammel. 'The 2005 contest in Germany was very different. The liberal employment market reforms Hartz IV were fought over, and it was possible to have an opinion either way on it. But here? Royal’s only message revolves around her being a woman, while Sarkozy’s speech about problems in the suburbs are completely targeted towards gaining the vote of the extreme right wing.

Vote with your feet

According to official reports from the French Institute for National Statistics (INSEE), around 1.9 million Europeans lived in France in 2004, forming the biggest immigrant group after those of North African descent. However, the numbers post-2004 are now under question, since EU citizens no longer require a residence permit to live in France. What is sure is the fact that most EU immigrants have no French citizenship and therefore are frozen out of the French elections.

Some are voting with their feet, like Sabine, a 26 year-old from Belgium. After extreme-right National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen gained entry to the second round of voting in 2002, she decided to join the public demonstrations against him. 'That was the only chance I had to speak out against him. As Europeans, this is the only way we have of expressing our opinions.' Sabine was born in France, but as both her parents are Belgian nationals, she had to decide whether to keep or relinquish her Belgium passport. She chose to keep it.

Despite being denied the vote, Sabine considers the question of public participation in politics as one of the most significant. Working for the Press Department of a mayor’s office in a Parisian suburb, she explains in bitter tones the everyday failings of democracy. 'The way clients are dealt with there annoys me a lot. The mayor often gives gifts to various interest groups, which on the whole has very little to do with democracy.'

Sabine does however believe that Royal is different, especially after seeing her at the forefront of citizens debates. 'She was really interesting and passionate. For me, Royal has an affinity with the people.'

Three colours for the stars and stripes

The fact that the campaign is being fought on the basis of national identity - and not on Europe - naturally strikes an uneasy chord with EU citizens. Sarkozy has announced that an accession to office for him would mean the creation of a ministry for immigration and national identity. Royal meanwhile has called for all French homes to display the red, white and blue flag. 'Italy, Great Britain and Germany see the least debate about Europe,' complains Sammel. 'We have to understand that being a European doesn’t mean giving up one’s national identity.'

Martina Colombier, a 48 year-old Austrian who has lived in France for 20 years, views the nationalistic rhetoric of the campaign as a reflection of a sense of worry sweeping the nation. For her, the elections are 'embarrassing.' 'A lot is being said, but it has little substance to it. All candidates are swimming in murky waters. They're just about keeping their heads above water to stop themselves from drowning. Because they can’t agree on anything, they just raise the flag and play the Marsellaise.'

The aims of Sarkozy and Le Pen to tighten up immigration and security find little common ground with the Europeans we talked to. This apathy is however not a widespread trend. A study by the Ifop Institute revealed 17% of voters of Italian descent will vote for Le Pen, with around 8% of those of Spanish and Portuguese heritage casting their votes in the ballot boxes of the extreme-right.

The sixties saw a massive influx of migrants from all areas of southern Europe, all hoping to benefit from the booming industry. For them and their descendents, voting for the far right is no longer a taboo. Many of them are in favour of tougher intervention in the suburbs. They are worried that new immigrants could threaten their place in society.

The sixties saw a massive influx of migrants from all areas of southern Europe, all hoping to benefit from the booming industry. For them and their descendents, voting for the far right is no longer a taboo. Many of them are in favour of tougher intervention in the suburbs. They are worried that new immigrants could threaten their place in society.

'France is too bureaucratic'

Guy Benfield, a 37 year-old British citizen resident in France for the past six years, makes the comparison with this home nation. 'Sarkozy wants to exploit and alienate half of society. He’s like Margaret Thatcher: dangerous and capable.' The internet site worker, who has also worked in Italy and Holland, says he feels 'more European than English.' In a similar vein to the former British Prime Minister, Sarkozy wants to pass through liberal reforms. 'If he succeeds, the unemployment rate in France is bound to increase dramatically, just as it did in Britain under Thatcher,' predicts Benfield.

His fellow Englishman, David Spencer, believes differently. Despite his personal left-wing tendencies, the Paris-based marketing worker believes Sarkozy could hold the key improving economic conditions in France. Spencer criticises above all the limitations placed on the working week by former Socialist runner Lionel Jospin at the end of the nineties, which limited the amount of hours one can legally work to 35. 'In comparison to England, France is much too bureaucratic,' he says.

Reform would not be dismissed by Colombier either. The German teacher directs her criticism at the Carte Scolaire, which restricts parents to sending their children to the local school. 'Everyone knows that rich parents send their children to private schools. It would be better to just say ‘we are a land of differences’ instead of constantly ignoring it. But the French can’t get away from their ideals of equality and fraternity. When I tell them that in reality, it’s very different, I always get the same answer: ‘you wouldn’t understand: you’re a foreigner!'

In-text photo: Guy Bensfield (GB)

Translated from „Wir Europäer sind von den Wahlen ausgeschlossen“