Destination Wałbrzych: Is Ukrainian Immigration Fixing Depopulation?

Published on

Translation by:

Francesca PaoliniWałbrzych, a town in southeast Poland, is now dealing with depopulation. The phenomenon of Ukrainian immigration is helping to solve this problem. However, the immigrants' working conditions are still uncertain.

"Not only do we need the Ukrainian workforce, but so do their families. We need people who see our town as their new home." These words were spoken by Roman Szełemej, mayor of Wałbrzych, a town located in the south-west Poland. In the last decades, the town has lost more than 30,000 inhabitants. In other words, Wałbrzych is one of the places in Europe, which is suffering from the depopulation phenomenon.

However, Wałbrzych has experienced golden age in the past. Its age of economic prosperity corresponds with its entrance into the Second Reich of the 15th century. During that period, the area became renowned for its mines as well as textile, glass and ceramic industries. To some extent, the current situation of crisis is the consequence of the way in which the transition from a communist economic system to a capitalist one was carried out during the 1990s.

After World War II, Wałbrzych underwent its first wave of depopulation on a vast scale. Many citizens migrated to Germany. However, the new migrants coming from the neighboring regions of Eastern Poland - which will become part of the USSR following the War - were transferred to Wałbrzych. During the communist period, the town maintained its prominent industrial identity with three operating mines and many factories. So how did the current crisis come about?

To some extent, this is a consequence of the way in which the transition from a communist economic system to a capitalist one was carried out in the 1990s. Due to this transformation, public businesses were at first privatized, and then shut down. A considerable proportion of the population lost their jobs. In order to prevent the social collapse, the Polish government created a special economic area, encouraging businesses and companies to invest in that region. Despite some positive outcomes, the manoeuvre did not manage to stop the ongoing drain of human resources.

A new life in Wałbrzych

However, a few years ago something started to change . A new wave of immigration reached the town. In contrast with the past, people are now arriving from beyond the bordering area in western Poland, especially from Ukraine. Today, more than 4,000 Ukrainians work and live in Wałbrzych.

Some of them came just for a seasonal stay, others considers it as a leg of transit, waiting to find a better life elsewhere. But there are also people who want to move in permanently. The latter group of people is also the main beneficiary of a few welcoming initiatives, such as the Polish language courses which take place inside the offices of the local authorities. Apart from this, the Ukrainians often gather at the Orthodox church: their community is now considerably bigger than in the past.

"In order to meet the Ukrainian immigrant community, we have to go inside the factories."

The new citizens are not only employed by the companies located in the economic area, but also in the public service sector, such as transportation. In all this, despite the words of the mayor Szełemej, the local authorities have not yet created supporting or integration programmes addressed to their new inhabitants. For this reason, in order to meet the Ukrainian immigrant community, we have to go inside the factories.

Life stories

Before coming to Wałbrzych, Sveta was working in Poltava as a journalist, a town in the western central part of Ukraine. Because of the start of the War in Donbass, her days were soundtracked by the ongoing warplanes landing and taking-off at the military base close to the town. With the war nearby, Sveta could not live with her fear - that her two children would have to find themselves in a warzone one day. For this reason, when her husband found out that a Polish agency was employing Ukrainian citizens to work in Poland in the industrial sector, she decided to take that leap. At first, only Sveta's husband left. However, three months later, Sveta and their two children joined him. "We did not know exactly where we would have gone, but it did not matter. We only wanted to wake up without hearing the warplanes."

"Life is tough. I am not working in my field. But this is still better than what I got used to."

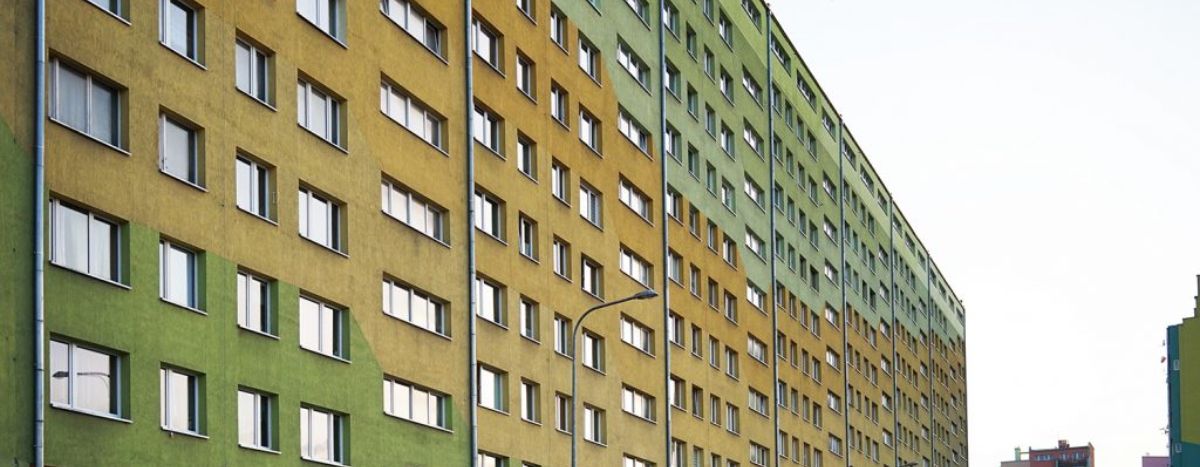

This is how Sveta's family got to Piaskowa Góra, an enormous housing complex in Wałbrzych, where hundreds of Ukrainian workers live. The agency moved them close by the Cersanit, a Polish factory that produces ceramic panels. Her husband is working in the warehouse, in the shipping department. Sveta, instead, is employed in the production line. She puts the glaze on polished ceramic items. "Life is tough. I am not working in my field. But this is still better to what I got used to in Ukraine," Sveta says. She explains that if she makes an error during the working process, the ceramic panel will become unusable. In order to get the minimum wage (10 złoty per hour), Sveta has to guarantee the success rate of 90 percent. In the case she does not manage to sustain this, the factory manager may reduce her monthly wage.

If Sveta is directly employed by her factory, she would earn more, given that the agency holds one third of her salary. Apart from this, her job consists in two working shifts made up of twelve hours, with the starting time at 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., as if to say: the kilns of the company never stop. As a matter of fact, this kind of life only allows Sveta and her husband to see each other only on Sundays. They work on different working shifts to look after their children. A better life for them was everything we wanted. The eldest is attending a Polish elementary school and is now comfortable with it. The youngest is still in nursery school.

"People still consciously perceive the troubled Ukrainian-Polish relationship in Wałbrzych deriving from the historical context."

Even though she came to Poland eight months ago, Sveta is still waiting for her temporary residence permit which will allow her to travel. Having to wait for their documents is the main problem for the Ukrainians living in Poland. Some of Sveta's friends had to wait nearly two years. Solitude is their second problem: "I bumped into Ukrainian people only when at work for a couple of months. A few days before Easter, a friend asked me whether I would have attended the mass. I was shocked when I realized there was an Orthodox Church in Wałbrzych. I had never heard of it for months. How could this happen?" Sveta asks herself. As we talk, other members of the Ukrainian community are present among whom Mariusz Kiślak, a Polish Orthdox priest. "Unfortunately, the majority of the Ukrainian people living in Wałbrzych know nothing about the church. But when you are an immigrant, being part of a community which shares similar problems is very important," comments Sveta.

Becoming grandparents in Poland

Olga and Sasha live in Wałbrzych too. Recently they have become grandparents, but their grandson was born in Ukraine: his parents still live there. They tell their story during a meeting in the local authorities' office, where the immigrants have the chance to attend a Polish language course.

Two years ago, Olga and Sasha were still living in a small village in Crimea. They decided to move abroad since they wanted to save some money for their future. Sasha's brother worked in Wałbrzych as a bus driver. Given that the public transports service needed new workforce, Sasha decided to move. Olga, instead, worked as a vet in Ukraine, but had to find another job in Poland. Her educational qualifications were not recognized and not admitted. "I worked as a housekeeper in many chemists' places. But exactly today I got fired. Do you want to know why?" she asks me infuriated. "I was fired after having an argument with a pharmacist who works there. This person has been having a bad behavior towards me for months and for long I have not understand why. Then, all of a sudden, they scold me: 'My grandfather was killed by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in the Second World War!' UP was, a paramilitary formation first, then it became a partisan one. They fought against the Nazi army of Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union with the aim to create an independent and united Ukrainian country. But how can I feel responsible for a story I have not even been part of?" asks Olga rhetorically. She made an official complaint by the chemist's management offices, claiming that this person did not have the right to mob her due to their family history. However, instead of solving the problem, she got fired.

Unfortunately, as absurd as it might sound, Olga's story is not the only case. In fact, many citizens in Wałbrzych are the descendants of families that were moved here after WWII and were from the Western regions bordering the Ukrainian territory. People still consciously perceive the troubled Ukrainian-Polish relationship in Wałbrzych deriving from this historical context. Luckily enough, contrary to Olga, Sasha is satisfied with his job as a driver. He works eight hours per day, six days per week. He plays the guitar in his free time and sings Ukrainian songs with his friends from the Polish language course. So, there is still room for a care-free life even in Wałbrzych. After all, Olga dreams of opening her Ukrainian restaurant: "I hope I will manage one day, be it in Wałbrzych or elsewhere, it does not matter."

The report is based on some interviews carried out with foreigners working in Wałbrzych, inside the framework of the project, Transeuropa Caravans. The protagonists' real names were modified due to privacy reasons.

Translated from Destinazione Wałbrzych: dallo spopolamento all'immigrazione ucraina