Curry Vavart collective in Paris: occupation as a prelude to art

Published on

Translation by:

Bethan MooreThe Curry Vavart collective has been active in Paris since 2004. It transforms the city’s abandoned and forgotten buildings into performance spaces, workshops, cooperative kitchens and shared allotments. Roaming around the city, they search for new spaces. Vincent is spending the afternoon going from the platforms of Gare de l’Est to an old body shop in the 20th arrondissement

‘The only condition is that there is at least one former railway worker among the members of the collective,’ begins Vincent Prieur, an artist, photographer and sculpture teacher in Paris. The 30-year-old is a member of the Curry Vavart collective. Founded in 2004, it has occupied two buildings at number 72 rue de Riquet, opposite the platforms of Gare de l’Est train station in Paris, since 2012. ‘We have a verbal agreement with SNCF (the French railway company – ed),’ explains Vincent, as the July sun forces his eyes half-closed. ‘They have granted us the use of an old locker room which is around 800 metres squared in size, as well as a training centre of around 600 metres squared.’ Both are surrounded by a garden scattered with bicycles and framed by the platforms of the station, and is known as Shakirail.

In the workshops

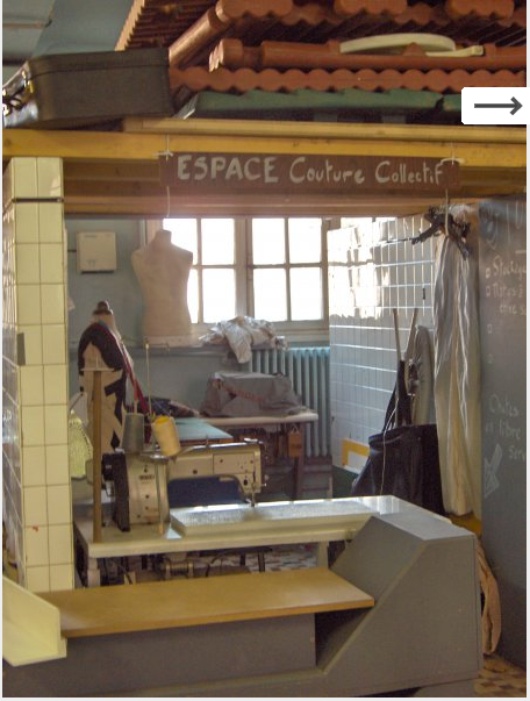

The gate shuts behind us and we cross the threshold. It’s a choice of the door on the left or on the right to discover a phantasmagorical workshop of wonders. The smell of the wood mingles with the smell of glue; traces of dye are spilled on the white of the plaster and the glare of the window pane. These are the laboratories of the artisans and sculptors. Everyone has their own workspace, from costumers to woodworkers, from set designers to special effects artists.

Griet De Vis, 35, works in theatre props and often spends her afternoons here. ‘If you are at the beginning of your career, this is an ideal place to work at,’ she says. ‘You can compare your work with your neighbour and learn new things. For example, I’ve taken up costume design and I’m even learning a bit of dressmaking.’ The average age of the crafts people at Shakirail is between 24 and 36. ‘You come here because you need the space,’ they explain, ‘then you stay for the social atmosphere, the sense of community and all the new friends you make.’

Griet De Vis, 35, works in theatre props and often spends her afternoons here. ‘If you are at the beginning of your career, this is an ideal place to work at,’ she says. ‘You can compare your work with your neighbour and learn new things. For example, I’ve taken up costume design and I’m even learning a bit of dressmaking.’ The average age of the crafts people at Shakirail is between 24 and 36. ‘You come here because you need the space,’ they explain, ‘then you stay for the social atmosphere, the sense of community and all the new friends you make.’

On the floor above, the rehearsal studio is set aside for performance groups. With wooden flooring for dancers, it houses the railway workers’ old lockers, where some still have names on them. There are also wrinkled seats, perhaps coming from what was once a waiting room. Opposite the rehearsal studio, the offices open up in a sort of living room, edged with piles of books, CDs and newspapers, and filled with armchairs and sofas. The collective relies on a network of around ninety volunteers to host approximately eighty performance groups a year, and who put on about a hundred shows. On the other side is the photography laboratory. A modest fee provides the use of its facilities and dark room to develop photos or take lessons provided by the two collective members who run it.

Saucepans, bicycles and shared allotments

To get to the second building, we pass the collective’s old vegetable garden. ‘Unfortunately no one looks after it anymore,’ says a bemused Vincent, who remembers how passengers used to be unnerved by the sight of a dozen crazy people gardening in the allotment a few feet from the station’s platforms. The kitchen is the heart of the squat’s communal life. ‘This is perhaps one of the biggest sinks in the whole city of Paris,’ jokes Vincent, as he explains how it was reclaimed from one of the railway workers’ old showers. On the lower floor, we enter into Yann’s realm, an eccentric bicycle seller who is wearing a pair of old railway boots. He shares his work shop with Camille, ‘who is never here’, and around a hundred bikes of all kinds, which are at times reworked and combined with scrap material and recycled objects.

To get to the second building, we pass the collective’s old vegetable garden. ‘Unfortunately no one looks after it anymore,’ says a bemused Vincent, who remembers how passengers used to be unnerved by the sight of a dozen crazy people gardening in the allotment a few feet from the station’s platforms. The kitchen is the heart of the squat’s communal life. ‘This is perhaps one of the biggest sinks in the whole city of Paris,’ jokes Vincent, as he explains how it was reclaimed from one of the railway workers’ old showers. On the lower floor, we enter into Yann’s realm, an eccentric bicycle seller who is wearing a pair of old railway boots. He shares his work shop with Camille, ‘who is never here’, and around a hundred bikes of all kinds, which are at times reworked and combined with scrap material and recycled objects.

Shakirail is not the first building to be occupied by the collective. They also have plenty of space in the Marchal, in the 20th arrondissement (district of Paris - ed). The old body shop has been renovated by Curry-Vavart, and for the 500 metres squared granted by the Paris city council, the thirty or so artists and artisans who work there pay a total rent of only 250 euros. ‘Everything started in 2004, in what used to be the Théâtre de Verre),’ says Vincent. Things continued with Le Gros Belec, Le Boeuf3 and Les Meubles, as well as other buildings which were occupied and then cleared out in the space of a few months. ‘This nomadic life has never discouraged us,’ jokes Vincent. ‘It’s like a challenge that we’ve accepted. It’s spurred us on each time, knowing that we don’t have much time available to make the most of a location’s potential.’

New ways of communal living

The collective, established several years ago, requires a formal managerial structure, but in reality there are no hierarchies, and a full and stable democracy is in force. ‘Every week we have a meeting where we make decisions together about the management of the spaces,’ explains Vincent. The organisation seems to work well, given that the collective manages to finance all its numerous activities itself. ‘Each resident regularly takes part in buying supplies with an agreed quota, based on their means and their use of the space. Each guest artist contributes a voluntary fee and the evenings organised by the collective help us to earn a total sum of nearly 30, 000 euros a year.’

Inside the building, supplies of wood, metal, glass and musical instruments are saved. ‘Everyone brings in anything they can get hold of,’ says Vincent. ‘There are people who work in galleries and museums bringing in unused materials from exhibitions and shows, and they make it available to everyone.’ In the workshops all the equipment is shared. If anyone has left a tool at home, they can be sure to find one in a neighbour’s area.

Inside the building, supplies of wood, metal, glass and musical instruments are saved. ‘Everyone brings in anything they can get hold of,’ says Vincent. ‘There are people who work in galleries and museums bringing in unused materials from exhibitions and shows, and they make it available to everyone.’ In the workshops all the equipment is shared. If anyone has left a tool at home, they can be sure to find one in a neighbour’s area.

‘We all know each other in this scene,’ says Vincent, referring to their relationship with another collective, Jeudi Noir, ‘but we have a different way of thinking.’ Curry Vavart does not insist on the concept of occupation but rather on one of sharing. ‘We want to implement new opportunities for participation and innovative ways of bringing these big spaces to life. They have been abandoned for so much time; we want to make sharing them a new way of life,’ says Vincent. He reveals that they are already planning to take on the management of a further building this autumn in order to ‘be able to rely on having a space, a part from where you live, in the type of buildings that help inspiration.’ So in this city of 11 metre squared apartments, having even just a corner of an 800 metre squared workshop would expand more than a few horizons.

Translated from Curry Vavart, se l'occupazione è un preludio all'arte