Crisis in European journalism

Published on

Translation by:

Helen SwainBetween the precarious nature of the work and fear for the vocation, journalism hardly dares to testify anymore against its patrons, the big communications companies. The public’s right to information is decreasing alarmingly as a result of the current economic crisis

‘Never in such a short time has there been such a decrease in pluralism and such a rapid loss of the very substance of democracy – freedom of information and of expression,' denounces Audije Alpaca, deputy general secretary of the FIJ (fund for investigative journalism). In the United Kingdom and Spain, in a single year, 3, 000 media jobs have been lost; Germany has lost about 1, 000; and in Italy and Poland, there have been between 2, 500 and 4, 000 dismissals. According to official sources, these figures may be much higher in reality, and they do not take into account the conditions for freelancers, who are widespread in the European Union, especially in the countries newly integrated into Europe. Only in France does a form of ‘intermittent contribution’ exist, which ensures a degree of security in times of scarcity of work.

Contradictory vocation

To be a journalist is a vocation, but at the moment, it could be a double-edged sword. ‘If you complain, you may lose your job, even though it is precarious and badly paid,' explains Paco Audije. ‘The worst,’ he adds, ‘is that we are supposed to be the whistle-blowers of society, and we are supposed to describe our miseries.’ Indeed, the EFE, the largest Spanish news agency and the fourth largest in the world, has been doing just that.

To be a journalist is a vocation, but at the moment, it could be a double-edged sword. ‘If you complain, you may lose your job, even though it is precarious and badly paid,' explains Paco Audije. ‘The worst,’ he adds, ‘is that we are supposed to be the whistle-blowers of society, and we are supposed to describe our miseries.’ Indeed, the EFE, the largest Spanish news agency and the fourth largest in the world, has been doing just that.

However, this bravery has not been sufficiently extensive to prevent staff cuts. Marosa Montañés, president of the Mediterranean women journalists association, believes that: ‘Journalists’ worst enemies are other journalists.' ‘The effort to be heard before anyone else, the thirst for exclusivity and the individualism that goes along with this profession’ are detrimental to the urgently required creation of a corporate unity, to ‘be attentive to the abuses that are taking place.’ From students’ first exercises in their final year at university, ‘there should be a norm to protect them from being the cheap, exploited manpower they have become.' This fact surprises Tanya Kostyuk, a 25-year-old Ukrainian who says she feels ‘satisfied’ with the remuneration that is given to scholarship recipients from her country. ‘Our journalism school is hard, but it guarantees decent work; the contrast with Europe is peculiar.’

'There should be a norm to protect journalists from being the cheap, exploited manpower they have become'

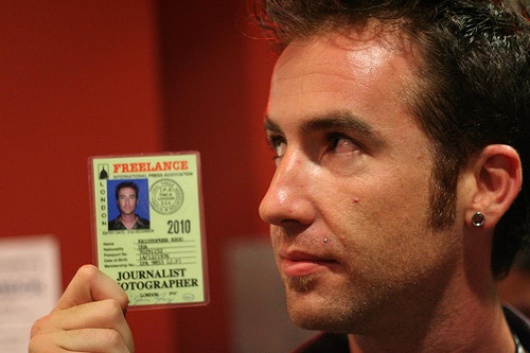

On 16 May, journalists from all over Europe gathered in Varna (Bulgaria) to oppose the restructuring which is being undergone by most of the media. However, this was a dubious declaration of intention when faced with the diversity of journalistic traditions in the Europe’s legislative tower of babel. Paco Audije is convinced that not everyone agrees with the journalism schools. The criteria are diverse, including the norm of self-regulation ingrained in the Nordic countries; the ‘ordine’ in Italy, which attributes professional identification for a system in which landlords, publishers and the magistracy are also present; and the commission for press cards which also includes trade unions and employers, and the incorporation of this accreditation by a press council in Germany or the UK.

Quality as an antidote

‘Our readers, listeners and viewers are fair people who immediately recognise the quality of our work and who, with the same rapidity, have started to associate it with our name. This is the moment when one becomes a steady journalist. It is not the directors who decide, but our readers.’ Ryszard Kapuscinski was already giving this advice in 1999 to a roomful of young journalists in Capodarco di Fermo (Italy). It was the best way to combat a lack of rigorous, veracious, complete information, published in rushed conditions and between staff cuts. An antidote to what the majority of so-called journalists produce.

Everyone from the IFJ down knows that specialised, well-known journalists are expensive, but there are no economic machines or mechanisms that can substitute quality. The BBC was criticised for its cover of the November terrorist attacks in Bombay because for many hours, it accepted unfiltered text messages from practically anonymous sources and ran them onscreen, rather than news from its own correspondents and information from reputable agencies.

Everyone from the IFJ down knows that specialised, well-known journalists are expensive, but there are no economic machines or mechanisms that can substitute quality. The BBC was criticised for its cover of the November terrorist attacks in Bombay because for many hours, it accepted unfiltered text messages from practically anonymous sources and ran them onscreen, rather than news from its own correspondents and information from reputable agencies.

‘The societies of the news screens,’ as Marosa Montañés calls them, can ‘be appreciable; the feedback, the social development of citizen journalism, networks, and so on, are infinite’; as long as they are not used to diminish the role of the professionals, who are increasingly burdened with all sorts of digital devices. ‘We must learn to use new developments – but the media, like business, can only be saved by professionalism and truthfulness,’ points out Paco Audije. ‘Changes in the profession should not be obstacles, but should stimulate what is required of quality journalism. I will maintain this in the face of those who only give us stories of accounts of results, without thinking about the origins of the disaster, and also in the face of those who follow new technologies blindly and are incapable of adapting to other ways of doing things.’

'Media, like business, can only be saved by professionalism and truthfulness'

This is a quality which prevails over attempts to manipulate the power of the media, such as Silvio Berlusconi’s media domination in Italy, Nicolas Sarkozy’s with his links to media leaders in France, or the censorship of the booing of the Spanish national anthem during the transmission of the final of the ‘Copa del Rey’ (football cup) in Spain, on national channel TVE. It's an aptitude for opposing the excesses perpetrated by the great communications groups, whose excessive ambition has led to their failure.

Translated from El periodismo en crisis: La Voz sin voto