Could a 'River' Lead Greece's Political Clean-up?

Published on

Translation by:

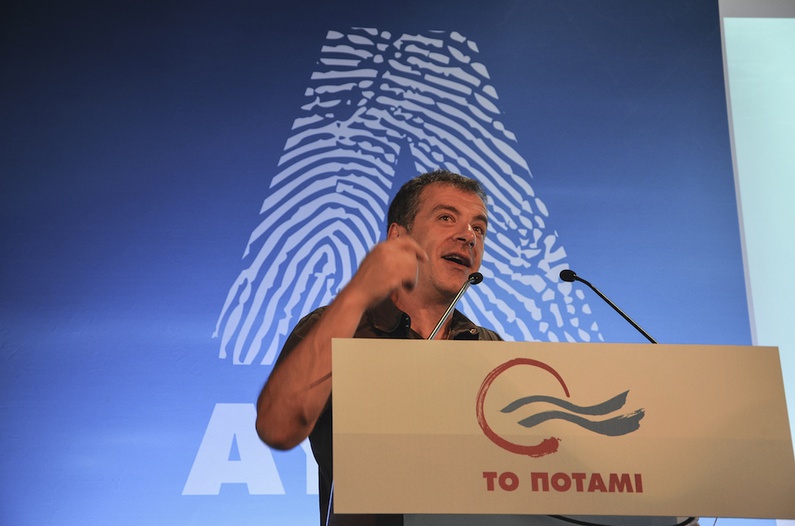

Thomas McGuinnOne of the best known Greek journalists, Stavros Theodorakis, has tried his hand in politics and founded The River, this season’s breakout party in the Hellenic Republic. Pro-Europeanism and the rejection of traditional party politics are some of the qualities which characterise it, but its supposed rejuvenating message is not immune to its own share of criticism and scepticism.

Stavros Theodorakis is not the usual kind of political leader. You know: wearing a T-shirt, carrying a rucksack around and making his way through Athens’ diabolical traffic on a bicycle. He is at ease in front of the cameras, most likely thanks to his long spell as a television reporter. He is the leader of Το Ποτάμι (To Potami), or The River, the youngest of the political parties at the forefront of Greek political life. It is an organisation managed to claim 6.6% of the votes in last May’s European elections in three months alone.

The outbreak of the financial crisis, which was particularly brutal on Greece, led to the formation of numerous parties of every ideological stripe and disappeared rapidly. “To Potami came later on,” explains Angelikí Berbilini, political correspondent for the weekly newspaper Athens Voice, “and it’s come to fight Syriza (radical left) for the votes of the centre-left members of the electorate who became orphans after PASOK went under.”

The outbreak of the financial crisis, which was particularly brutal on Greece, led to the formation of numerous parties of every ideological stripe and disappeared rapidly. “To Potami came later on,” explains Angelikí Berbilini, political correspondent for the weekly newspaper Athens Voice, “and it’s come to fight Syriza (radical left) for the votes of the centre-left members of the electorate who became orphans after PASOK went under.”

It is surprising that a new party has been so successful, considering the fact that Greece has experienced an almost alternating political system between PASOK (Social Democrats) and New Democracy (Christian Democrats) since the fall of the military dictatorship in 1974, leading to the creation of a caste. For example, for 24 years in four decades since democracy, the country has had a prime minister with the surname Papandreou or Karamanlis. To Potami aims to change this by recruiting people from outside the political arena. “The people at To Potami are some of the best in the country: professors, scientists, artists, athletes. There is not one politician by profession,” points out Dimitris Fyssas, another journalist for Athens Voice. “They don’t have any problems with their past and, most importantly, each and every one of them talks about their specialist field.”

Nevertheless, there are some people who think that this reshuffle of names does not guarantee anything. “The problem is not with the people; it is systemic and institutional,” states Mary Karatza from Place Identity, a study which looks for ways to increase participation in decision-making processes. “I’m disappointed in To Potami when they say that ‘we are good, they are bad’. The problem cannot be solved by replacing some people with others who are supposedly better; there needs to be a change of system." Karatza believes that the big issue behind this problem is the Greek Constitution of 1975, which she considers to be an empty text which is easily manipulated by the government. “Theodorakis needs to be brave and approach the subject: we need a new Constitution. The current one just perpetuates the lack of transparency and doesn’t encourage the development of society.”

However, Place Identity doesn’t just have bad things to say about Theodorakis and his party. Stephania Xydia, the other half of the project, tells me that she likes it. “And I like Theodorakis for two reasons: one, because he has been all around Greece to listen to what society needs, and two, because he asks good questions.” And this is something that the Athens Voice journalists agree with: the importance of Stavros Theodorakis’ charisma when it comes to analysing the party’s good results in the elections. “Theodorakis created it, he started it,” says Fyssas, and thanks to him and his fame, it has survived.

When you get to the party’s office, you may well think that you were entering a co-working space with tables occupied by various people with their laptops. I am welcomed by Lina Papadaki, press secretary for the party who worked with Theodorakis before as a journalist. “A few years ago we started out by making short documentaries about social issues, and it is from there, from witnessing so many stories, that we got the idea of founding the party,” she tells me in the hustle and bustle of the office. “Stavros realised that the people were asking him to do something more.” And this is when I meet the man that everyone has been talking about, Stavros Theodorakis, who is walking around the office in a T-shirt. Yes, he may well be wearing a T-shirt and carrying a rucksack, but that does not stop him from being a political leader, and at least, he comes over to greet this foreign journalist who has come to try and understand what it is that he and his team are doing to be the success story of Greek politics.

Rodis Sabbakis is a young member of the team who was the assistant campaign manager for Giannis Boutaris, the popular mayor of Thessaloniki, the country’s second-largest city and a public supporter of the new political organisation. One of the first things he mentions is the pleasant atmosphere which everyone soaks up and he points to his shorts to show that he can dress as he likes. Rodis seems proud to work with Το Ποτάμι, a party which, according to him, combines social democratic concepts with other liberal ideas without defining itself as right- or left-wing. When asked about the rejection that the party has received because of this, Sabbakis says that it’s logical. “It’s understandable, but it’s actually much easier to create an identity for yourself when you’re under constant attack,, and he concludes, by adding: “But, in the European Parliament we have aligned ourselves with the group of Socialists and Democrats, which does say quite a bit about our inclination.” The group’s two Euro MPs have indeed joined the socialist group as independent members and the formation has been praised by the European Socialist Party’s candidate for the Presidency of the European Commission, Martin Schulz, who said that it was a “serious, progressive and pro-European” party and that it was “collaborating in the fight against the forces of evil.”

Forces of evil which were not named by Schulz but which manifest themselves somewhat in the streets. A walk around Athens is a visit to a museum of posters and graffiti, many of them political in nature. On one of them, signed by a group of far-left militants called AKEP, To Potami are likened to the governing parties New Democracy and PASOK, claiming that they are three branches from the same tree. “We think that part of the system is wrong,” says Rodis, when I show him the picture, “but the fact that this is being done means that we’re doing something right.”

The survey polls are giving them just as much hope. After achieving 6.6% in the European elections, they are now supposed to have gone on to obtain 9.5%, according to a recent publication by the prestigious public opinion company Public Issue. Thus, they now occupy the third place after beating the far-right party Golden Dawn. “If the elections were tomorrow, we would be ready to run, there is no doubt about it,” claim Lina Papadaki and Rodis Sabbakis at the party’s offices. And this is confirmed in the news room of Athens Voice. “They will make it to the elections,” says Dimitris Fyssas, “and things could either remain the same as they have until now or To Potami could play a part in bringing about great change in Greece.” We’ll have to wait until Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’ government decides to call elections, presumably in the spring of 2015, to see whether this river, which seems so clean, transparent and well-managed, is able to burst the banks of the radicalisation of Greek society and political life.

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE DEDICATED TO ATHENS AND IS PART OF THE EU-IN-MOTION PROJECT INITIATED BY CAFÉBABEL WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION.

Translated from Un 'río' para limpiar la política griega