Calm Lebanon ‘crisis’: Blackberrys not Kalashnikovs

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)On 12 January, eleven ministers from the the unity coalition government resigned en masse. Western backed caretaker prime minister Saad Hariri has refused to be a part of a coalition potentially led by the militant Shia muslim group Hezbollah

Saad Hariri is the son of the former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri, whose 2005 assassination may be linked to Hezbollah, according to a UN probe. Hence the tensions. But this is not a national crisis. It's another notch on a rather long belt of political difficulties in the country. Lebanese life goes on as routine; it’s almost serene. I was still holidaying in Barcelona before returning to Beirut, so I followed the news of a future Hezbollah-backed government leader with interest. The European media employed dramatic headlines such as ‘serious political crisis’ in an effort to bring this small country closer to the western Middle East.

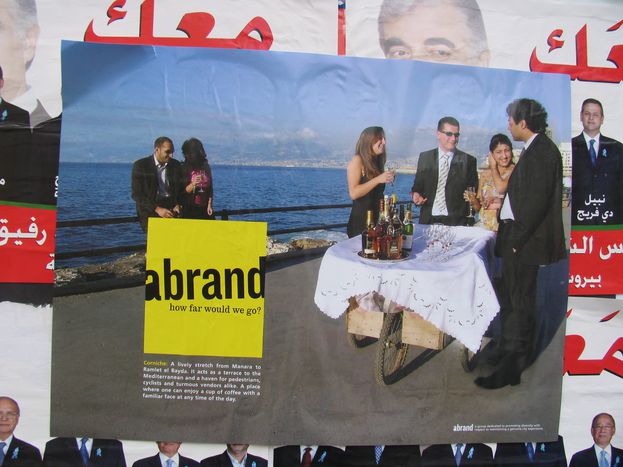

I wondered how people were doing, especially in the eastern Beirut neighbourhood of Achrafieh where I spent six months, and which is a dedicated Christian enclave. Had they stopped going for cocktails in the bars of Gemmayzeh, which according to any Lebanese I had met, stayed open during the month-long Hezbollah-instigated 2006 war with Israel? Had they even started using the traffic lights to avoid their daily traffic jams?

I wondered how people were doing, especially in the eastern Beirut neighbourhood of Achrafieh where I spent six months, and which is a dedicated Christian enclave. Had they stopped going for cocktails in the bars of Gemmayzeh, which according to any Lebanese I had met, stayed open during the month-long Hezbollah-instigated 2006 war with Israel? Had they even started using the traffic lights to avoid their daily traffic jams?

As my friends informed me, life goes on as normal in the streets of the capital. Each and every person brandishes a Blackberry and they’re practically all hanging out at the trendy ABC Mall. The most dangerous thing could be walking around and dodging kamikaze cars, but for the moment no-one’s drawn their Kalashnikovs in the open air. Those noisy nocturnal explosions remain fireworks in the distance. In other regions such as Chouf, a mountainous central town overlooking the Damour river valley, the biggest change that citizens see is in the increased military presence on the roads.

cafebabel.com meets Saad Hariri: read the interview

I landed in Beirut in mid January and spotted no changes as I crossed the pro-Hezbollah neighbourgoods of the city on my way back from the airport. The flags are in their places. Posters of the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, dating from his first ever visit in October, gather dust on the sides of the motorways. This country is so used to political shambles that the mass resignation of various politicians is almost nothing new to them – it wouldn’t be so in the mentality of an average European. Lebanon is a country where now and today matter, and where you always expect the sun to rise tomorrow. Not that we’re limiting Lebanon’s options. Who knows that once these lines go onsite, someone might just have gone out ransacking the streets or the capital with their gun. Welcome to Lebanon, the age of possibility.

Images: main Paul Keller/military Razan Ghazzawi/both courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Líbano: No cambiamos Blackberry por Kalashnikov (de momento)