British, Italian and German architects give Europe a face

Published on

Translation by:

claire mcbride

claire mcbride

Openness, transparency, efficiency: which buildings need a democracy? We span the European parliament, palace, court of human rights and Central Bank

European parliament: Greece on the Rhine

European parliament in Strasbourg (Photo: ©inyucho/ Flickr)

The  political centre of the European Union stands for architectural innovation: since 1990, the European parliament has assembled in the Louise-Weiss building on the north-eastern border of Strasbourg. The building is named after a French female politician, feminist and European activist from the twenties. Its design is the successful result in the attempt to give European democracy a place to live. The French office Architecture Studio, which won the international competition in 1991, unites the formative style principles of European architecture across 220, 000 square metres of land. The cross and the ellipse dominate the building – the contained classical form and the sweeping lines of the Baroque period.

political centre of the European Union stands for architectural innovation: since 1990, the European parliament has assembled in the Louise-Weiss building on the north-eastern border of Strasbourg. The building is named after a French female politician, feminist and European activist from the twenties. Its design is the successful result in the attempt to give European democracy a place to live. The French office Architecture Studio, which won the international competition in 1991, unites the formative style principles of European architecture across 220, 000 square metres of land. The cross and the ellipse dominate the building – the contained classical form and the sweeping lines of the Baroque period.

Externally the parliament’s structure is divided into an arched part of the building with a conference room, where there is also a plenary hall and a tower for the offices of the MEPs. The unfinished, unusual eastern face of the tower is a cause for speculation: is it based on the colisseum in Rome? Or is it a tower of babel facing in an easterly direction? According to the image of Architecture Studio, visitors meet a mainstay of western democracy in the publicly accessible tower: the Greek Agora, the debating square of old Athens. As a counterpart to the plenary hall the round, public square takes up the inside of the office tower. However the former, with its closed off dome, doesn’t emanate anything like the transparency of the glass dome of the Reichstag in Berlin

European palace: a knight’s palace with the charm of the seventies

European palace: a knight’s palace with the charm of the seventies

European senate in Strasbourg (Photo: ©Kpalion/ Mai2004)

You can see immediately that the Louise-Weiss-building is actually a ‘deluxe domicile’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung) for Europe’s representatives just by looking at the European palace that it is a neighbourhood. In 1977, the square building with its conventional outer structure was made according to plans drawn up by French architect Henry Bernard. In this concept Europe seems less fond of discussion than in the new parliament building: according to Bernard, the face of the 38-metre-high construction should be the embodiment of the strength and unity of the EU. However inside the building Bernard preferred a curvy construction method, showing a free circulation of ideas and opinions. To this day the European palace is the home of the European council. Up until 1999 the parliament met here due to the lack of an alternative building

Deliberative: the European court of human rights

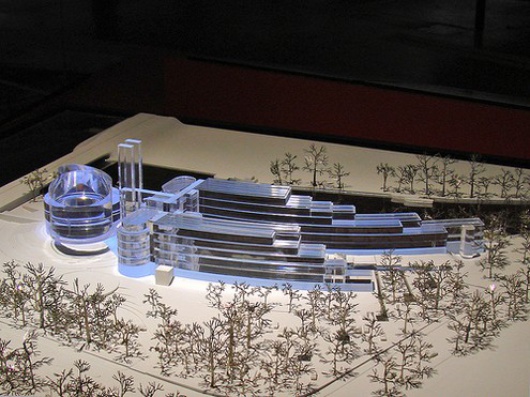

Architecture model, Strasbourg by Richard Rogers & architects/ Paris exhibition 2008 (Photo: ©dalbera/ Flickr)

Architecture model, Strasbourg by Richard Rogers & architects/ Paris exhibition 2008 (Photo: ©dalbera/ Flickr)

Goddess Justice  holds a pair of scales in her hand. The allegory may have been the inspiration for star architect Richard Rogers, whose Heathrow Terminal 5 has just been unveiled outside London, for his framework of the European court of human rights. At least from a birds-eye view, the circular conference halls in the court building resemble two colossal dishes. The building was completed in 1995 and forms the ‘magical triangle’ in Strasbourg’s European quarter, along with the Louise-Weiss-Building and the European palace. According to the will of the architect the court, made of steel and a glass façade reflected in the adjoining rivulet, is not meant to be a ‘monument’, but a ‘symbolic landmark’ that Europe can have a ‘credible image’. Rogers, a British architect of Italian origin who won the Pritzker architecture prize in 2007, encompassed the basics of justice in his buildings: transparency and perfect clarity. However the symmetry of the construction has a very prosaic cause in its original administrative structure of the court. Until 1998, the court was also home to the European commission – each one having a home in their own curved dish

holds a pair of scales in her hand. The allegory may have been the inspiration for star architect Richard Rogers, whose Heathrow Terminal 5 has just been unveiled outside London, for his framework of the European court of human rights. At least from a birds-eye view, the circular conference halls in the court building resemble two colossal dishes. The building was completed in 1995 and forms the ‘magical triangle’ in Strasbourg’s European quarter, along with the Louise-Weiss-Building and the European palace. According to the will of the architect the court, made of steel and a glass façade reflected in the adjoining rivulet, is not meant to be a ‘monument’, but a ‘symbolic landmark’ that Europe can have a ‘credible image’. Rogers, a British architect of Italian origin who won the Pritzker architecture prize in 2007, encompassed the basics of justice in his buildings: transparency and perfect clarity. However the symmetry of the construction has a very prosaic cause in its original administrative structure of the court. Until 1998, the court was also home to the European commission – each one having a home in their own curved dish

Big finance: European Central Bank (ECB), Frankfurt am Main

Temporary site of the ECB, Frankfurt am Main (Photo: ©Mike from Zurich/ Flickr)

Temporary site of the ECB, Frankfurt am Main (Photo: ©Mike from Zurich/ Flickr)

In February 2008  the city of Frankfurt-am-Main was awarded planning permission, with work beginning in April. The eastern border of the main metropolis at the site of the former Great Market Hall will be the site of the European Central Bank . The Austrian architect design firm Coop Himmelb(l)au plans to build an 185-metre-high office tower consisting of a glass atrium and two individual towers twisting amongst each other. This, according to the Viennese architects, is a symbol of ‘transparency, efficiency and stability’ - features of the construction which should also apply to Europe’s currency keepers.

the city of Frankfurt-am-Main was awarded planning permission, with work beginning in April. The eastern border of the main metropolis at the site of the former Great Market Hall will be the site of the European Central Bank . The Austrian architect design firm Coop Himmelb(l)au plans to build an 185-metre-high office tower consisting of a glass atrium and two individual towers twisting amongst each other. This, according to the Viennese architects, is a symbol of ‘transparency, efficiency and stability’ - features of the construction which should also apply to Europe’s currency keepers.

Until about 2012, the ECB will stay in the Eurotower in Frankfurt’s town centre, which was altered in the nineties for the ECB. Before building even gets underway though, the planned Skytower is already a problem child. In 1928 the former Great Market Hall was listed under a preservation order, which is why the heirs to architect Martin Elsaesser protested vehemently against the new construction being built. The original proposal of Coop Himmelb(l)au was to fend off the protests. There was meant to be a conference centre in the form of a skyscraper right next to the Great Market Hall.

Until about 2012, the ECB will stay in the Eurotower in Frankfurt’s town centre, which was altered in the nineties for the ECB. Before building even gets underway though, the planned Skytower is already a problem child. In 1928 the former Great Market Hall was listed under a preservation order, which is why the heirs to architect Martin Elsaesser protested vehemently against the new construction being built. The original proposal of Coop Himmelb(l)au was to fend off the protests. There was meant to be a conference centre in the form of a skyscraper right next to the Great Market Hall.

Skytower - new ECB site (Photo 2006: ©dontworry)

Now the latter itself is to be altered to become the conference hall. The demolition of the side of the hall and the construction of a glass cross-bar over the industrial monument are still on the agenda – and is the subject of much discussion in Frankfurt

Translated from Bauherr Europa