Belgium partition: voice of the populace

Published on

Translation by:

catherine e. moir

catherine e. moir

Almost three months after the Belgian legislative elections, negotiations with a view to forming a government are still in deadlock. The country hopes for better days

A strange black, yellow and red flower is to be seen in abundance throughout the streets of Belgium. Never in living Belgian memory has there been so much nationalist fervour, since rumours surrounding the country’s fate have been circulating. If there is an abundance of flags on balconies in Wallonia and Brussels, then they are bitterly conspicuous by their absence in Flemish towns, where a separatist fever seems to predominate, growing as the days without a government wear on.

Separatist issue?

'I’ve always loved Belgium,' says an old man, interviewed on the streets of Antwerp. 'But watching how the crisis is panning out, I want to tell the French-speakers to work it out without us!' His perfect French, with not a trace of an accent, is testimony to the difference in language-learning patterns, particularly between Flanders, where most of the native Flemish-speakers have French as a second language, and Wallonia, where the native French-speakers tend to have little or no Flemish.

'We have hinted many times to the Flemish that they would be better off without us,' replies Aurelie, an economics student in Brussels. 'I think some people have got a vested interest in dividing the country as much as possible, especially by splitting the social security system. The Flemish politicians make the average citizen believe that their life would be better without the French-speakers. But the trade unions, the remaining things that is not yet divided in this country, aren’t being had and are calling for unity!'

This observation is shared by Christelle, who works for Stib, the Brussels metro, and who claims not to have any problems working with her Flemish colleagues. 'We are the same. I find it ridiculous that people are trying to pit us against one another.'

Language matters

'The difference stems from the language, of course,' Aurelie continues. 'It’s a vehicle for culture, which separates us for sure. The other day I wanted to watch a political debate on Flemish television to see their point of view on the political crisis. I saw clearly that it was very different to ours. In Flanders they aren’t even talking about the same topics. And my knowledge of Flemish is not sufficient to understand the content well enough and in enough depth.'

How can this linguistic chasm be explained when Brussels schoolchildren have twelve years of language lessons, working out at four hours a week? 'I speak German, English and Spanish fluently,' says Aurelie. 'But their language really isn’t attractive, even though I love going out in Flanders – Gent and Leuven are great cities, and even my boyfriend is Flemish!'

How can this linguistic chasm be explained when Brussels schoolchildren have twelve years of language lessons, working out at four hours a week? 'I speak German, English and Spanish fluently,' says Aurelie. 'But their language really isn’t attractive, even though I love going out in Flanders – Gent and Leuven are great cities, and even my boyfriend is Flemish!'

If it is the case that the Flemish are different and their language is unattractive, why carry on living with them? 'The country is already so small, can you imagine if it were cut up into two or three?' replies Sandrine, a public relations student from Wallonia. 'It’s true that Flemish isn’t easy, but that isn’t why it is not attractive. Incidentally I am doing my Erasmus year in Flanders, not in some sunny country!' she laughs, saying that the young people from both communities have a lot to gain by learning to get to know each other.

If it is the case that the Flemish are different and their language is unattractive, why carry on living with them? 'The country is already so small, can you imagine if it were cut up into two or three?' replies Sandrine, a public relations student from Wallonia. 'It’s true that Flemish isn’t easy, but that isn’t why it is not attractive. Incidentally I am doing my Erasmus year in Flanders, not in some sunny country!' she laughs, saying that the young people from both communities have a lot to gain by learning to get to know each other.

Antwerp voice

'Do you realise that if we separate, we’d be on CNN - the shame of it!' jokes Anouk, a young resident of Antwerp, born in Haiti. 'Sure, the Wallonians could make more of an effort with the language, but after all we are all still human. We should be able to live together. Everybody in my class thinks the same.'

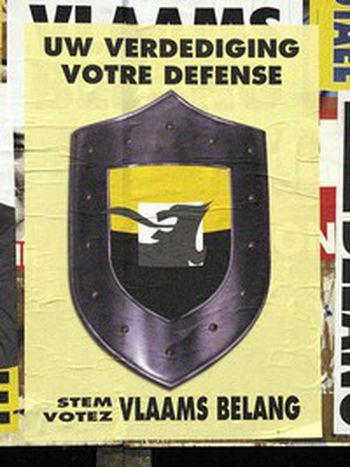

But is this discourse representative of Antwerp, a city which has continuously for the last ten years given a third of its votes to the separatist extreme right? A huge Belgian flag, ten times as high as those on the balconies in the capital, appears, next to the sign of a bar. 'This is the only country in the world that has no proud identity nor any sense of chauvinism,' explains the bar owner. 'That’s also why I like it! Look at the French and the Germans, so proud of themselves. We are the exact opposite. This flag doesn’t provoke any feeling in me, except a short sharp slap in the face for the extremist minority who wants to separate people who have never had a problem among themselves.'

In-text photos: Park 'Cinquantenaire', Brussels (il.norge/ Flickr), Ghent city centre (trqmgd/ Flickr)

Translated from Partition belge : d'accords en désaccords