Ataka Bulgaria - every path leads to nationalism

Published on

Translation by:

kate hollinshead

kate hollinshead

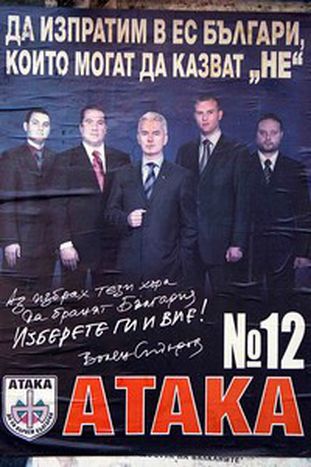

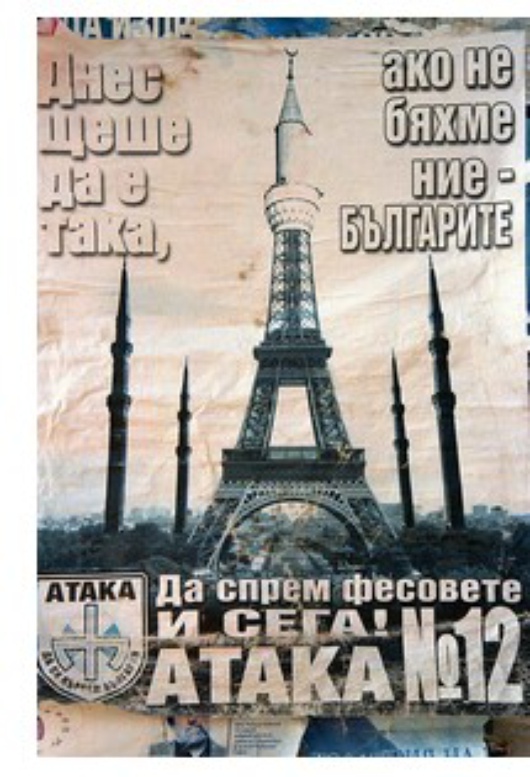

Party propaganda for the nationalist party feeds their public with xenophobic messages on a daily basis

‘Turkisisation.’ ‘Separatism.’ To the right of the picture the Bulgarian flag flies and today, 130 years after the liberation of the so-called ‘Ottoman Yoke,’ the documentary film ‘The New Slavery’ leaves no doubt that the Turkish dominance in southern areas of Bulgaria has long since gone. Whilst being the audience winner of the cable television channel SKAT in the past year, the six-part documentary series was also the media mouthpiece of the nationalist party, Ataka, radically straightening out the alleged ‘life-long illusions’ of Bulgarian politics, the peaceful cohabitation of different ethnic groups, since the changes of 1989.

Ataka: media party

Ataka’s success story starts in the television studio, for the party is a clone of the TV show of the same name that was established by their boss, Volen Siderov. Before his political career, he was a journalist, initially chief editor for the anti-communist daily newspaper Demokracija, and then for the populist newspaper Monitor. Siderov is a political chameleon: firstly a supporter of the reform movement ‘Unification of Democratic Forces,’ he sympathised later with Simeon, a former tsar returning from Spanish exile. In the last year he developed a radical – nationalist political position for the first time in his life.

The white-haired man with a penetrative stare was quite rightly known as author of three conspiracy-theory monographs on one hand and through his appearances on the cable television channel SKAT on the other. In his daily ten minute One-Man Show he launched attacks against anyone who did not fit in with his plan: Romans, Jews, foreign investors and homosexuals. This still continues today, even as a member of the National Assembly.

The nationalist manifesto continues to spread via a second medium – the daily Ataka.  The 24-page newspapers are filled with reports about the criminality of gypsies and threats of projects to build new mosques as well as regular interviews with members of Ataka.

The 24-page newspapers are filled with reports about the criminality of gypsies and threats of projects to build new mosques as well as regular interviews with members of Ataka.

‘For both Ataka and SKAT there is no difference between media publicity and political publicity,’ says Orlin Spassov, a media scientist from Sofia. ‘The party Ataka started out as a media party. It is no coincidence that the name of the party and the name of the newspaper were assumed from Siderov’s TV programme on SKAT. Since the changes in 1989 SKAT is the only TV station which has a party in this way.’

The Siderov Show

Siderov has transformed his degree of popularity in the media into political gains. In summer 2006, shortly before the parliamentary elections, he established his party Ataka – the first party since 1989 to politicise xenophobic resentment – and promptly secured eight per cent of the vote. Ataka was now part of the National Assembly. At the presidential elections in October 2006 Siderov succeeded even as far as the second ballot, competing against the current incumbent, Georgi Parvanov. What’s more, after the polls for European parliament, Ataka could consign three of a total of 18 Bulgarian members of European parliament. These are members of the newly-established extreme right-wing fraction ‘Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty’ which is affiliated with Jean Marie Le Pen’s Front National and Greater Romania Party (‘Partidul România Mare').

Action against ‘unbulgarian’ media

Ataka lives up to its name as a party of the media. In the eyes of the group, the media is frequently branded as ‘unbulgarian.’ In February 2007 Ataka supporters stormed the editorial offices of WAZ, the Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung in Sofia in order to personally take to task the editors of the weekly newspaper 168 Hours because of an unpopular article published within it. The defense of Bulgarian spirit is brought forward in the party’s own media once again and represented as successful propaganda. The main core of the voters, who are also consumers of other mainstream media, find themselves in a hermetic, never-ending cycle of information. The cycle traps you: there is no place for protest any longer.

Hate speech goes unpunished?

Fierce reactions have come from civil society. Thus the initiative citizens against hatred brought Siderov before the law because of such discriminatory statements against minorities. Juliana Metodieva is the only successful claimant so far. ‘Siderov’s statement Bulgaria for the Bulgarians has discriminated against me because I am of Armenian dissent,’ explains the journalist from Sofia. Many processes drag on, especially due to tactical delays by Siderov’s counsellors.

In the media domain itself mechanisms of control have caught on quite slowly. In November 2004 representatives from over 160 media companies signed an ‘Ethic Code’ which would contribute to improving fairness in the daily news. This is the first attempt to instill ethical principles into Bulgarian journalism. Yet neither Ataka nor SKAT are members of the code. For them, the code of conduct is not in force.

And whilst journalists, NGOs and other organs of democratic control wonder how one could proceed against the media controversy caused by Ataka, currently at least, the group is at arm’s length. Ataka’s type of media has established a new journalistic style, a nationalist discourse which is prepared daily for both the newspapers and the airwaves.

*Partidul România Mare, or Greater Romania Party, is a Romanian political party, led by Corneliu Vadim Tudor. It promotes strongly nationalist policies and is seen as the most right-wing of the major Romanian parties

*WAZ, Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, is a big German press and media group with a branch in Bulgaria

Funded by the 'Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft' foundation

This article was first published in the German journalist network N-ost

(In-text photos: Dagmar Gester)

Translated from Bulgarien: Nationalismus auf allen Kanälen